REXENTERTAINMENT

“The phrase that I have come to believe best sums up what the documentary film can most hope for, is to ‘undermine the simplicities’. The challenge is to present a much needed sense of flawed humanity not stereotypes.”

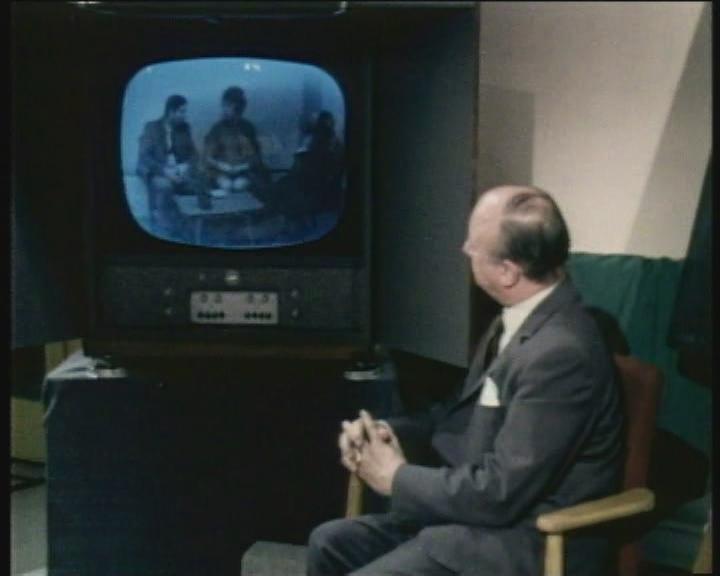

Rex Bloomstein

Rex Bloomstein has made over 150 single films, television documentaries and series and, in January 2012, presented his first radio documentary, Dying Inside for Radio 4. He is currently developing a number of further projects.

For full details about his work, follow the links below.

The building retracted into itself. She – soft flesh – edged her way out. It’s two years now. Two years since her mother buried herself past saving. There’s no gravestone yet. Just clean grass, waiting.

[from ‘The House’ by Aviva Dautch]

Award-winning poet, Aviva Dautch, lets us into the secret of her childhood home in Salford. From sleeping in the bath to emptying thirty-two tonnes of rubbish from the house after her mother’s death, Aviva shares what it means to be the child of a hoarder and how her lyrical, precise images seek to make order from the chaos in which she grew up.

This programme is a voyage into the past, but also one of discovery for Aviva, who has never before talked to others who have had similar experiences or to specialists in the field. She tells her story, weaving together her poems and conversations with

Background

Her mother barricaded her in behind household goods, newspapers, rotting vegetables, until the house became its own creature in the child’s mind….

Aviva’s mother suffered from obsessive hoarding syndrome, a condition now officially recognised by the World Health Authority as a mental illness, but when Aviva was growing up in the 1990s there was a culture of silence around the problem. Hoarding was the way Aviva’s mother created a place of safety, a refuge, but for Aviva their home became a prison.

Far from the stereotype of the sad, eccentric hoarder, Aviva’s mother was a successful paediatrician and geneticist, a member of the team working on the development of IVF She’d left the team not long before the first baby, Louise Brown, was born as she was pregnant herself (with Aviva). She would go on to become an expert in Tay-Sachs disorder. Academic studies have shown that hoarding is more common in women, especially women who are carers: social workers, nurses, therapists or, as in Aviva’s mother’s case, a doctor. There seems to be a strong link to trauma, with the onset linked to bereavement or loss – the hoarder’s post traumatic response is to literally bury themselves alive.

Aviva reflects on her experiences as the daughter of a hoarder, absorbing recent research that has explored how fear and shame lead children of hoarders to hide their living conditions from outsiders. Not only are they embarrassed about the condition of their home, their self-perception is that they are worthless as their parents seem to care about objects more than them. Secrecy about the home is intensified by fear of parental reactions. As children get older, the psychological cost of accommodating the disorder becomes more apparent. They become more conscious of their own vulnerability, helplessness, disgust and social isolation. Like Aviva, many become totally estranged from their families; some become hoarders themselves and others obsessively tidy.

The Program

Poet Aviva Dautch revisits her childhood as the daughter of a chronic hoarder.

Questions about how she or, indeed, others could cope with such conditions under the restrictions of lockdown inform how Aviva tells her story, weaving together her poems and conversations with friends: professional declutterer Miriam Osner, her former schoolteacher Sherry Ashworth, and actor Juliet Stevenson.

Juliet reads from the poems of Emily Dickinson, who spent much of her life in solitude but wrote expansively about the world. Aviva and Juliet explore why her poems reverberate for them in the current moment and discuss the positive aspects of isolation, the necessity of the arts for helping us feel less alone and how creativity can be a response to adversity.

The programme features poems from Aviva’s Primers Three sequence (Nine Arches Press: 2018) and her work-in-progress debut collection We Sigh For Houses, which has received an Authors’ Foundation Award from the Society of Authors.

Presenter: Aviva Dautch

Producer: Rex Bloomstein

Exec Producer: Brian King

Sound Engineer: Matt Peaty

Hebrew liturgical music sung by Michal Ish-Horowicz

About Aviva

Aviva Dautch teaches English Literature and Creative Writing at the British Library. She has a PhD in poetry and her poems, reviews and literary essays are widely published. She won the Poetry School /Nine Arches Press Primers Prize for Emerging Talent in 2017 and received an Authors’ Foundation Award from the Society of Authors in 2018. Her first full collection, We Sigh For Houses, is due to be published in early 2021.

‘Aviva Dautch is a powerful young poet, whose work engages very intelligently with serious issues, but who has a formal dexterity and a command of social tone that makes her feel approachable; she’s someone to watch for the future and someone to enjoy in the present.’ Andrew Motion

‘Aviva Dautch’s poetry is distinguished by its musicality, linguistic clarity and precision, depth of thought and feeling.’ Mimi Khalvati

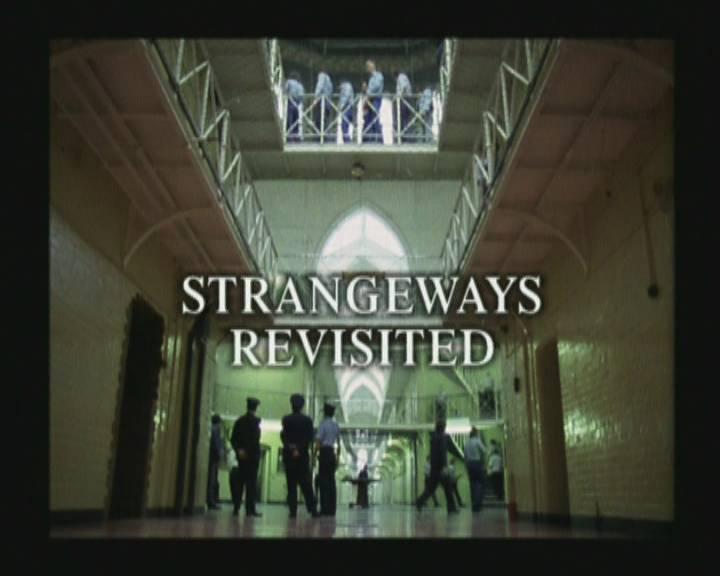

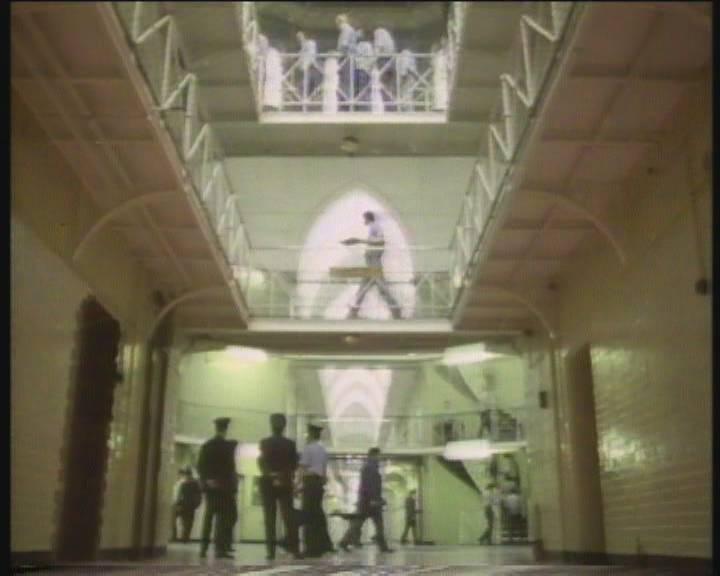

This is a film about hope.

The hope experienced by prisoners who, written off by society, have been thrown a lifeline and offered a path away from criminality and back towards redemption and normality.

At its heart it confronts stereotypes and public perceptions of ‘The Offender’ by presenting both serving and ex-prisoners as real people with real problems. Crime can ruin lives – of the victims, of course, but also of the perpetrators who not only have to deal with their own feelings of guilt, but are also then stigmatized by society, making it difficult for them to recover from what they have done, even after they have completed their sentence. Lacking support, many inevitably re-offend.

The vicious cycle of re-offending rates is an urgent story of our time. The figures are stark.

Almost two thirds of those released from the UK’s prisons are convicted of another crime within 12 months if they fail to find a job – 50 per cent more than those who do find work. Re-offending costs the UK tax-payer an estimated £15 billion a year. And yet the vast majority of employers openly admit they will not employ an ex-offender.

There are exceptions.

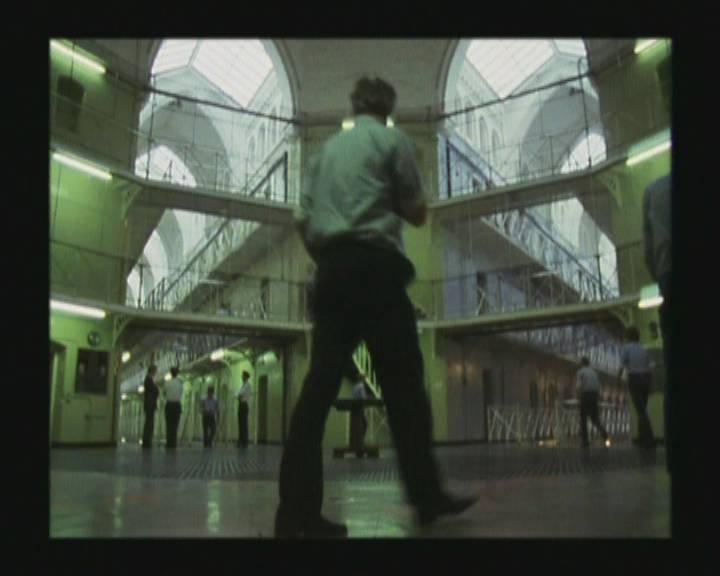

Embedded in a number of UK prisons are training academies run by Timpson, a leading high street retailer specializing in shoe repairs, key cutting and engraving, as well as photo processing through its subsidiary, Max Spielmann.

Timpson have forged new ideas in the recruitment of ex-offenders and now employ over 600 up and down the country. Their pioneering prison academies offer hope in exchange for hard work to a selection of inmates coming to the end of their sentences. All are fascinating because of the challenge to prisoners, both career criminals and first timers, to seize this opportunity to change the course of their lives.

This 90-minute feature documentary accompanies two serving prisoners on their journeys through this unique training programme – each with a genuine chance of employment on their release, if – and it is if – they don’t mess up the opportunity.

These journeys are punctuated by encounters with four former prisoners, now Timpson and Max Spielmann employees, who have embraced the world of work and are now living normally outside the walls.

These are vignettes of real lives, we see them at home and at work, interacting with customers and taking pride in their jobs. Reflecting on their own journeys from criminality to hard graft and an honest wage they delve into their backgrounds, their crimes and their regrets; their experiences in prison and how they grasped the opportunity to re-train. They relive the crucial moments that transformed their lives – those moments that led to hope, change and ultimately to redemption.

A Second Chance is a unique glimpse of lives regained. Instead of simply presenting the familiar bleak universe of the prison system, this is a film that documents the transformative power of work for those who want to change, the importance of employment as well as of forgiveness and remorse.

I have made many films about the UK prison system over the last 40 years or so.

Now, in 2019, the crisis it faces in terms of overcrowding, violence and re-offending is unprecedented. And yet, as a society, we remain addicted to imprisonment.

With over 90,000 men and women crammed into around 140 jails, Britain has the third largest prison population in the whole of Europe – behind only Russia and Turkey. And the trend is upwards.

If we are to reverse this – and it currently costs the taxpayer over £40,000 a year for every single person behind bars – attitudes have to change. Attitudes towards not only who should be in prison and the kinds of crimes that need to be punished by locking someone up, but also how to begin the process of rehabilitation so that convicted men and women don’t re-offend, don’t find themselves back inside, and instead make that choice to rebuild their lives after release back into society.

The truth remains that most prisoners leave custody with no job and, dogged by the stigma of their sentence, little prospect of finding one. Many have lost their homes and almost everything they possessed. How can they possibly put their lives back together?

With no money, no income and precious little hope, for too many it’s simply too easy to return to drug abuse, to criminality and, almost inevitably, to prison. But not all offenders should be written off and many deserve a second chance – for their own good and for the good of us all.

I met James Timpson, Chief Executive of the Timpson Group, through our work with the Prison Reform Trust. When he told me that, unlike the vast majority of employers, he has made ex-offenders a major source of recruitment and has even opened training academies inside some prisons, I began to explore the idea of making a film about some of these trainees as well as former prisoners now working in Timpson’s.

The more I researched, interviewed and listened to a variety of serving prisoners and ex-offenders – people whose lives, for whatever reason, had been so impacted by their descent into criminality – the more I recognized that work can be a key component to rehabilitation. It can restore a sense of pride and self-worth as well as providing that all important income and sense of stability.

And, as employers like Timpson have discovered, the benefits to offering this second chance to offenders genuinely outweigh the risks. Many are former career criminals and not all are a success, but those I met who really wanted to change their lives told me how much it meant to have this opportunity to turn away from a criminal path.

What greater challenge could there be for those who have offended against society? The challenge to return to society, and gain self-respect through work.

In the face of so many negative factors and reports on the prison system, this film has been a rare opportunity to tell a more positive story of what can and should be achieved. It also reveals how devastating the temptations of crime can be for the person caught up in criminality and for their families.

My hope is that A Second Chance will do as our title suggests, become a catalyst for breaking down perceptions, challenging stereotypes and opening the eyes of the public, employers and the prison system itself to the importance of work as a key to tackling the profound problem of re-offending.

The Guardian, Eric Allison

At a time when the prison system is in meltdown and reformers in despair, [A Second Chance] offers a glimpse of hope and inspiration and, above all, shows what can and should be done if we are to make headway in the battle against reoffending… This absorbing film sends the message out – quietly but clearly. The prime minister would do well to listen.

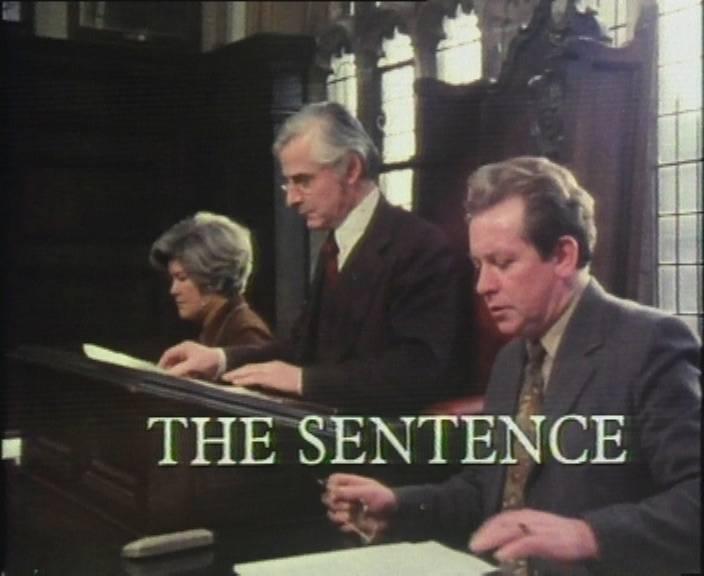

Every year the Parole Board releases thousands of prisoners, including those convicted of the most serious violent offences. Rex Bloomstein made the first ever television series on parole in the 1970’s, and now 40 years later, has been given unprecedented access to go inside the parole system today and reveal how decisions are made.

He meets prisoners ahead of their crucial hearings and listens in on the entire process as parole panels interrogate the prisoner, prison and probation workers and psychologists. The panels finally conclude and explain their decisions - to release or not to release. The consequences of possibly getting it wrong, weigh heavily on them. For the prisoners, the tension leads to tears and anger.

Across the two programmes, Rex Bloomstein talks to Parole Board chief executive, Martin Jones and former chair, Nick Hardwick, who was forced to resign after the High Court quashed a parole panel’s decision to release serial sex offender, John Worboys.

Is the Parole Board sufficiently accountable, transparent and effective? Is its independence now under threat?

I wanted to consider the following elements to help reveal the parole process:

a) The prison – what parole means to them.

b) The prisoners – their hopes and expectations.

c) The parole board panel – the recording of several aural hearings with the agreed necessary safeguards.

d) Interviews with key figures on the Board to consider future developments for Parole and the implications for the prison system and society.

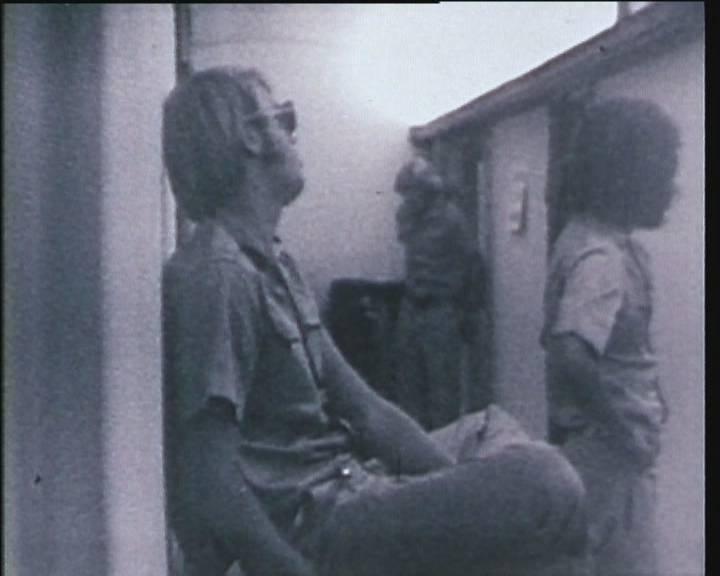

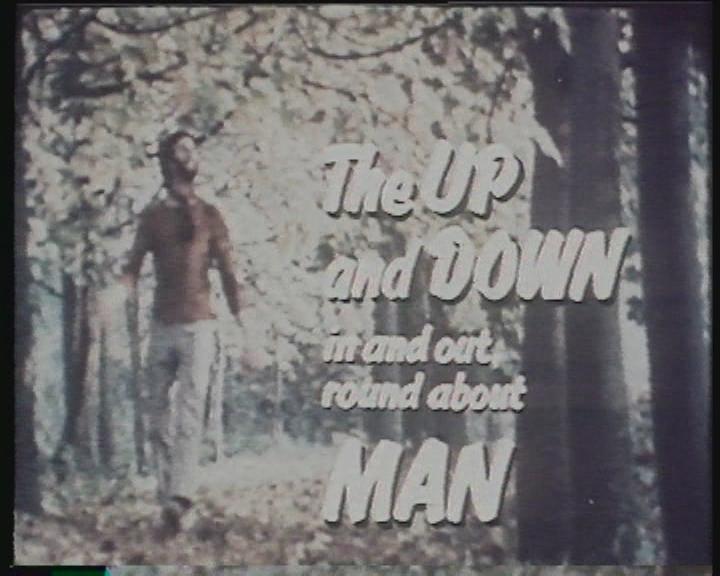

I wanted also seek to contrast the work of the present day Parole Board with excerpts from my seventies BBC TV series, Parole, which explained a number of aspects of the parole system and with it the opportunity of early release, the incentive to turn a life around, the chance for hope. Parole at that time was severely criticized as arbitrary and impenetrable. Some thought it actually cruel, as no reasons were ever given when a request for parole was turned down, often leaving a prisoner in a despairing limbo at the mercy of a ‘secretive bureacracy’.

The Parole Board had never been filmed and had refused all previous requests, but they finally agreed to this 2-part study broadcast in 1978. We followed 4 prisoners applying for parole and showed three different cases of a parole board panel’s discussion including an arsonist, a cannabis offender, and the case of a young sex offender followed by comments from the then chairman of the Parole board, Sir Louis Petch, which illustrate the assumptions and thinking at the time, and my critical conclusions on the parole system as it was practiced then.

It is interesting to note, that all the concerns, which were raised in the programs about the parole system have since been met. Parole has become automatic for prisoners serving fixed term sentences over 12 months. Prisoners have the right to an oral hearing - the right to be represented – the right to know reasons for refusal – the right to appeal. The Parole Board is no longer an advisory body but a type of court in its own right, dealing with mainly indeterminate sentences and reviewing disputed decisions to recall prisoners back to prison. Whilst questions continue to be asked over the Board’s independence and its transparency, its role had profoundly evolved since our filming.

Rex Bloomstein

GERALD is 49, and has spent more than half his life in prison. His weaknesses are heroin, and a penchant for armed robbery. The dossier on him runs to more than 300 pages, and includes robbing banks at gunpoint. The most recent incident occurred three years ago, when he broke the terms of his parole and attempted to rob a mobile-phone shop, threatening the owner with a syringe of blood.

He is now reapplying for parole, and, in his statement, declares that he is not a violent person. With the irony of a seasoned professional, the parole-board assessor regards this claim as “arguably surprising”.

Everyone was, throughout Parole: A calculated risk (Radio 4, Friday), scrupulously polite to one another; and I wondered whether our subjects were behaving themselves especially well for the benefit of the fly on the wall. Nevertheless, Rex Bloomstein’s documentary gave a valuable insight into the workings of a system which, in recent months, has attracted enormous criticism.

After the proposal to release John Worboys, the reversal of that decision by the High Court, and the subsequent resignation of the chair of the Parole Board, there was never a better time to examine what goes on in those parole-panel assessments.

Much has changed in the past 25 years. Prisoners can be represented by solicitors, and victims are given the opportunity to provide statements. Psychologists and prison staff are all consulted; and, in Gerald’s case, contribute to a picture of a genuinely reformed individual. He will be released, under strict conditions; and, as the man from the Parole Board was happy to tell us, the proven failure rate in such cases is very small. The trouble is that even one failure can be catastrophic for victims and for the reputation of the Board.

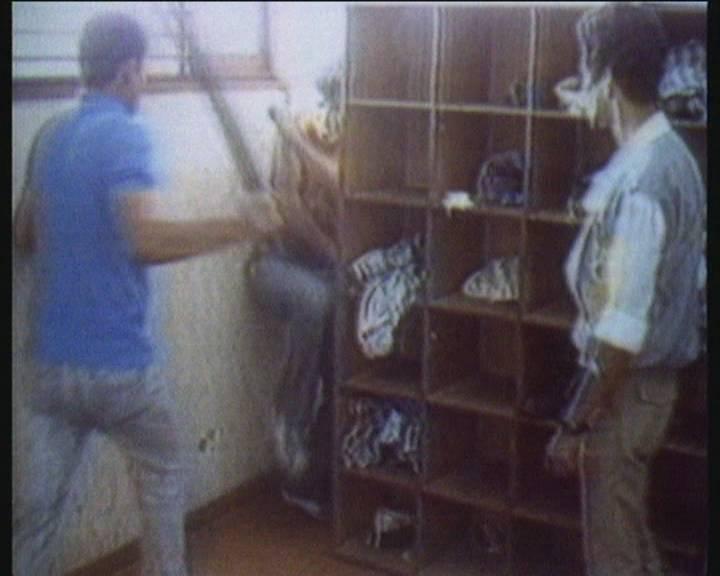

Rex Bloomstein meets musicians from around the world who are raising their voices against political, cultural or religious intolerance in the face of often brutal repression. He talks to artists whose songs have led to their imprisonment, torture and to the continuing threat of violence; artists who have been driven from their homelands, artists who, literally, risk dying for a song.

In one recent year alone 30 musicians were killed, 7 abducted, and 18 jailed by regimes, political and religious factions and other groups determined to curb the power of music to rally opposition to them. In Syria, singer Ibrahim Quashoush, was found dead in the Orontes River, his vocal chords symbolically ripped out.

Rex hears stories of tremendous courage and determination not to be intimidated and silenced. Egyptian singer Ramy Essam, tells of how he was brutally tortured after his songs rallied the crowds in Tahir Square during the Arab Spring. Two weeks later, after recovering from his injuries, he was back performing his songs of protest. Iranian singer Shahin Najafi continues performing around the world despite the issuing of a fatwa calling for his death, after his songs upset the religious leaders in his home country. He says: “At night I turn to the wall and slowly close my eyes and wait for someone to slit my throat”.

Amid tales of musical repression in Sudan, Tunisia, Burkina Fasso and Lebanon, come more surprising stories from Norway where Deeyah Kahn talks of death threats aimed at stopping her singing and Sara speaks about her struggle to sing the music of the indigenous Sami people.

The documentary filmmaker Rex Bloomstein gains unprecedented access to HMP Whatton in Nottinghamshire, the largest sex offender prison in Europe, to investigate how its inmates are rehabilitated for release. Since the revelations surrounding high profile figures such as Jimmy Saville, Rolf Harris, Max Clifford and the publicity created by Operation Yewtree, there are now more sex offenders in the prison system than ever before. Around 11000 out of a total population of nearly 86000 in England & Wales.

HMP Whatton, with its capacity of 841 prisoners, is a specialist treatment center for sex offenders – 70% of whom have committed offences against children, the rest against adults. Bloomstein has been allowed a unique opportunity to explore the methods used to confront inmates about their crimes and prepare them to go back into the community. The prison’s governor Lynn Saunders describes ‘Whatton as a great leveller, prisoners come from all walks of life’, and both child & adult offenders are mixed together in the prison’s many Sex Offender Treatment Programmes.

Candid interviews with prisoners are at the heart of this documentary as they reveal how treatment is helping them to rehabilitate but Bloomstein discovers a paradox. Many sex offenders feel intense shame and guilt about their crimes as indeed society would expect. However, he learns such emotions can be a huge barrier to the treatment process as Whatton’s staff work hard to restore their self-esteem deemed crucial to their rehabilitation.

As the majority of Whatton’s prisoners will be released Bloomstein ultimately considers the issue of risk – how certain can we be that these men won’t commit terrible crimes again? Programme facilitator Dave Potter says – whilst there is no guarantee he profoundly believes the work done at Whatton gives its sex offenders the vital tools to control their behaviour in the future.

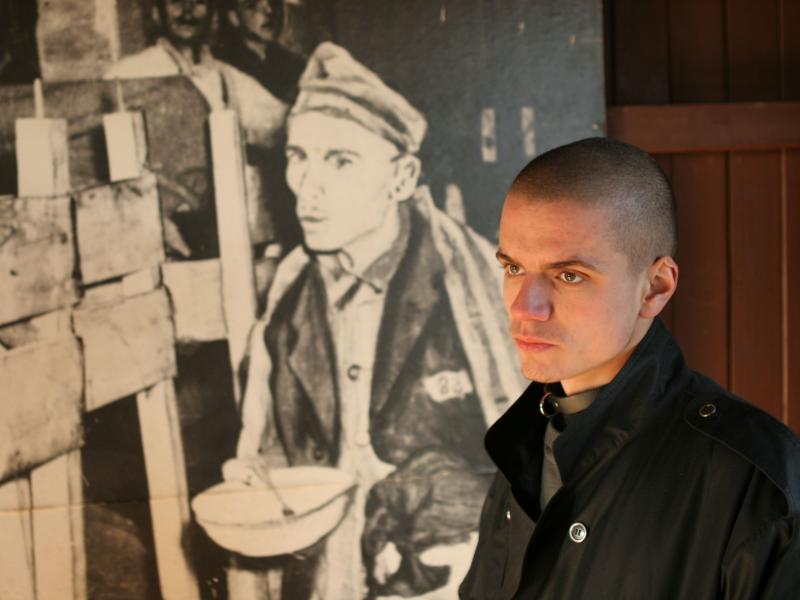

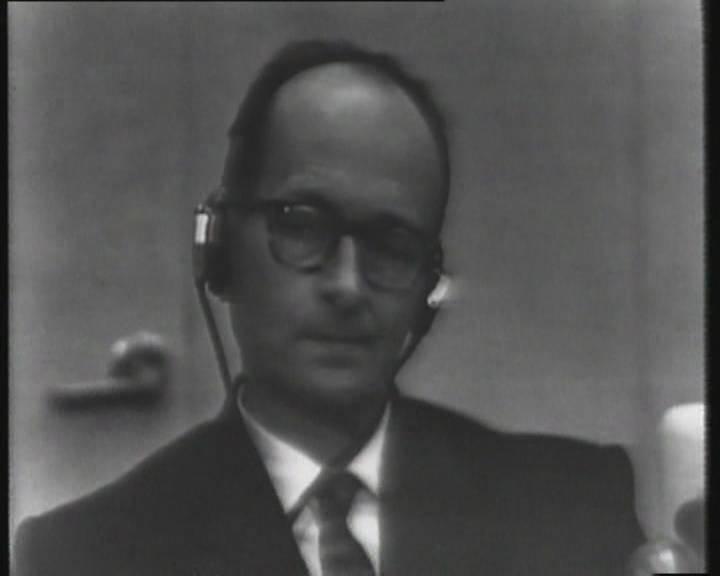

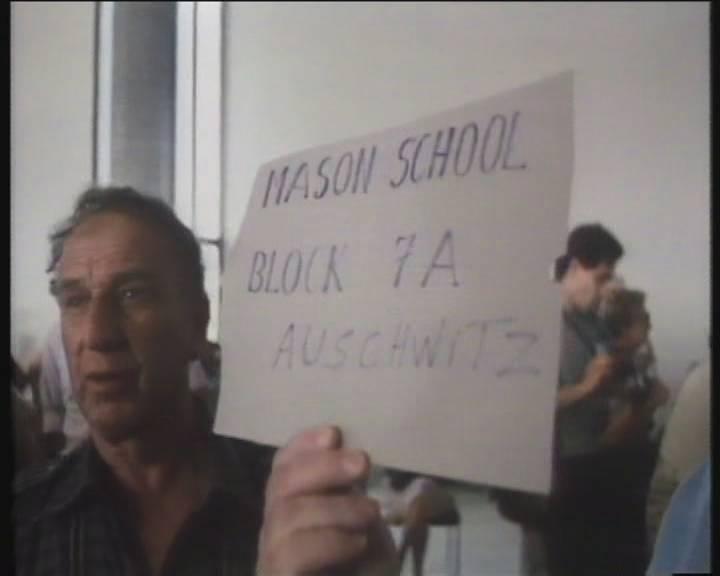

Rex Bloomstein has been a pioneer of the modern prison television documentary from the award-winning series ‘Strangeways’ in 1980, to the ground breaking programme ‘Lifer - Living with Murder’ in 2003. His Radio 4 documentary ‘Dying Inside’, on older prisoners co-produced again with Simon Jacobs, won a Silver Sony Radio Academy award in 2013.

The Observer, Miranda Sawyer

This seriousness was also evident in Rex Bloomstein’s absorbing Inside the Sex Offenders’ Prison, on HMP Whatton, the largest sex offenders’ prison in Europe. Phew, this was a tricky one. Bloomstein met men who had committed the sort of crimes you hope nobody you love will ever have to deal with: from internet porn to rape and child abuse. Some offenders were very depressed about what they’d done, some were pragmatic, others remembered their anger, at the world and themselves. Bloomstein asked all the right questions, and acknowledged when the answers were awkward. There are 86,000 people in prison in the UK; 11,000 of those are sex offenders. HMP Whatton’s in-depth rehabilitation courses are a way of trying to deal with this enormous societal problem. A documentary that will stay with you for some time.

Burma is a country in transition. Supposedly freer now, then ever before. But is this really the case?

In 2010, I made This Prison Where I Live, a campaigning documentary film about Zarganar, Burma ‘s greatest living comedian, who had recently been released from a 35 year prison sentence. In Burma: Art Under Dictatorship, for BBC Radio 3, I returned to Burma to interview Zarganar, during the film festival that this unique and hugely popular artist has created. With Zaganar’s co-operation, it opened the way to talk to fellow comedians, writers, musicians, painters. How free were they to write, perform and play their music: how free were journalists to comment and enquire and others to engage in more radical art forms? What really was the state of freedom of expression in Burma?

Since the dramatic release of Aung San Su Ki, Burma’s artists were playing a key role in reflecting the country’s changing landscape. Art reflects society. What happens to its artists reveals what is really happening to the society and country its people live in.

However, after the so called ‘political reforms’ of those years, I encountered an artistic community who felt just about safe enough to speak out and who revealed how much censorship still existed. Painter and performance artist, Nyein Chan Su, described how ten government officials from the Censorship Board came to his gallery earlier in the year, only to forbid the color red on some of his politically themed paintings. Nyein Chan Su said, “red is too suggestive a colour for a regime responsible for so much bloodshed before the reforms”.

The film producer, Myo So, discussed his two year battle with the censors to get his 2010 film, ‘Nostalgia’, about the student uprising in 1988, distributed without significant cuts, even though the film contained no scenes of actual protest. Myo So was still fighting that battle.

One of Burma’s foremost contemporary poets, Zeyar Lynn, who spearheaded a new form of Burmese poetry, spoke of not having to use introspective and emotional language so characteristic of living under previous dictatorships.

Han Too Lin, Burma’s most radical punk singer, described the ways he’s tried to defeat the censors over his lyrics and his satirical radio show they had since banned.

What I discovered was the scale of the country’s cultural impoverishment, with so few places to study, view and exhibit art.

At its heart this program engaged with those artists who through their work were fighting an ongoing battle for history and memory – hoping they were freer to confront their past.

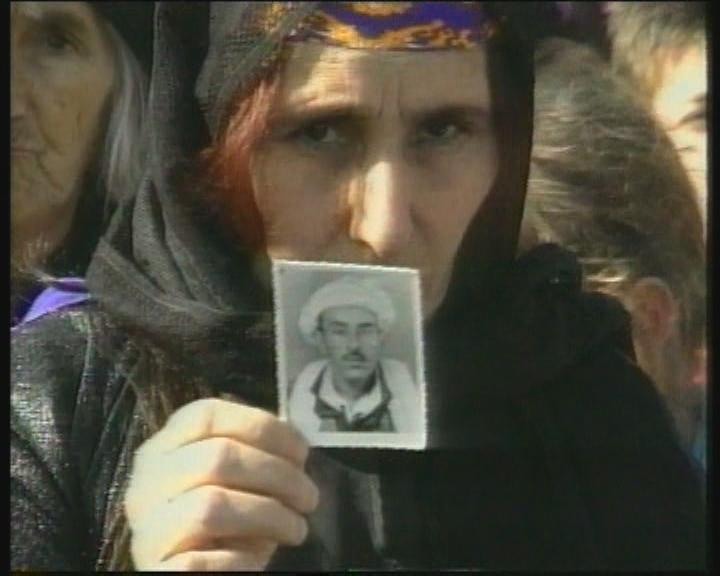

For this Archive on 4, Rex revisits these programmes and finds out what happened to those prisoners of conscience. Were some still in prison? What have those released done with their lives after torture and ill-treatment?

Of the 64 ‘Prisoners of Conscience’ shown on BBC 2 over those 5 years - over 40 were freed. Rex also reflects on the audience response, the politics of getting such programmes aired, the dangers of broadcasting them to the prisoners themselves and ultimately asks were they worth doing?

Prisoners featured in several of the series included :

So Sung - South Korea

The very first Prisoners of Conscience programme was presented by Sting in 1988. It featured So Sung, a student activist jailed by the South Korean Authorities and severely tortured. He was originally sentenced to death, but this was commuted to life imprisonment. In protest at his ill-treatment in prison he tried to commit suicide by setting himself on fire and is permanently disfigured as a result. So Sung was eventually released and is now a Professor in International Human Rights Law in Japan.

Mikhail Kukobaka - Russia

In and out of prisons, labour camps and ‘psychiatric hospitals’ for 18 years, Mikhail was serving a seven year sentence for anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda in the Perm 35 labour camp when he was featured in the 1988 series of Prisoners of Conscience. His offences included handing out a copy of the UN Declaration of Human Rights to co-workers. He refused to sign a confession but was released shortly after the broadcast and continued to be a regular NGO activist.

Riad al Turk - Syria

When he was featured in the 1989 series of Prisoners of Conscience, Riad had been in prison in Damascus for nine years for his opposition to the Syrian government. He had somehow survived the most prolonged and systematic torture which resulted in severe health problems, Riad al Turk was never charged or brought before a court. He was finally released in 2001 and lives in the Syrian city of Homs. Is he still alive?

Vera Chirwa - Malawi

One of Africa’s top women barristers, Vera had spent 10 years in prison in Malawi when featured in the 1991 series of Prisoners of Conscience. She and her husband had helped found the Malawi Congress Party, which campaigned for peaceful independence from the UK in the 1950s. They were kidnapped by Malawi police, tried and convicted of treason under the orders of President Banda and sentenced to death.

The trial was widely condemned as unfair and, after intense international pressure, Banda commuted their sentences to life imprisonment. Vera was released following the death of her husband in custody, and dedicated her life to human rights.

Manuel Manriquez - Mexico

Manuel was serving a 24 year sentence for the murder of a man he had never seen and whose name he did not know. Featured in the 1992 series of Prisoners of Conscience he is an Otomi Indian musician. Manuel was finally released from custody in 1999 after the Inter American Commission on Human Rights decided that his conviction was unfair and based on a confession extracted under torture. He lives in Mexico wher the admittance of evidence gained through torture remains a key human rights problem in Mexico.

Imen Derouiche - Tunisia

Imen was featured in the 1999 series of Human Rights Human Wrongs. She was one of 17 students arrested in Tunisia in 1998 after going on strike for improved study conditions. They were accused of being terrorists and she spent 18 months in prison before being tried on the basis of a confession extracted under torture. She endured beatings, injections and repeated threats of rape while in detention. Imen left Tunisia and is now a refugee in France.

In the late 1980s I noted a weekly column in the Times Newspaper called ‘Prisoners of Conscience’ written by the journalist and historian Caroline Moorehead. Of course the concept of ‘Prisoners of Conscience’ had been developed by Amnesty International, what Caroline was doing was to highlight individual cases of innocent men, women and children jailed in different parts of the world. It struck me that I could do the same in a series of short appeals for television. We first went to the UK’s Channel 4 who turned us down, and then approached the BBC who eventually accepted the idea.

We not only wanted to get the audience to watch such a series, but crucially to get them involved in trying to secure the release of these innocent people; to do what human rights organisations all over the world were doing – bringing attention to their wrongful imprisonment as well as the often appalling conditions and treatment such prisoners endured. The BBC eventually commissioned us to produce ten five minute programs to be shown Monday to Friday over two weeks and agreed that the series be transmitted to coincide with the 10th of December - Human Rights Day.

Presenters included two former prime ministers, distinguished scientists, famous sportsmen, provocative journalists, controversial writers, eminent actors and actresses, and yes, rock stars. The opening program in our first Prisoner of Conscience series in 1988 – was presented by Sting.

Some twenty five years later I wanted to revisit these programs, and find out what had happened to some of the people featured in the series – how had they fared? Were they even still alive?

So let me set out what were the main challenges in making the series; each program needed a minimum of visual evidence such as photographs of the prisoner, the prison he or she was held in and if it were not dangerous – photographs of the family as well. We had to give the facts and political context about each of the people featured in the countries that had imprisoned them and description of the tortures many of them had suffered as well as other violations of their human rights.

Our sources were primarily Amnesty International as well as Human Rights Watch and other human rights organisations and charities.

So what effect did we have? Audiences averaged a million and some 10,000 people overall either wrote or rang the BBC for an information pack that gave details of how and where to write on behalf of the prisoner. Of the 64 prisoners of conscience featured between 1988 and 1993 – we eventually discovered over 40 were free.

A 14 year old boy based in Eindhoven sent me this poem after watching the programs.

Jail in Japan

Eyes forward, no left, no right,

no daylight to be seen.

No people, no life to tell you why,

every night its all the same, change is not an option.

Pressure brings blood to your wrists that beg for freedom;

the windows with no glass aren’t on your side.

No one to see, no one to disagree with,

no one to tell it to.

No left, no right,

all is wrong that should make it right.

It was my hope that Prisoners Of Conscience and Human Rights Human Wrongs might have inspired other program makers in different countries to replicate the series, to do the same – using our example perhaps as a template. Because I believe with the right approach, you can make people care. But with the exception I think of Holland – it never happened. Perhaps it still should? At the very least the people featured in these programs were not forgotten.

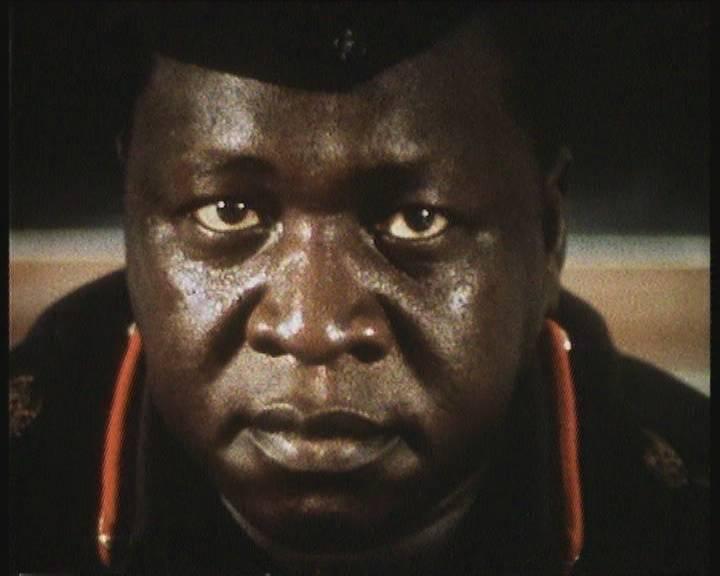

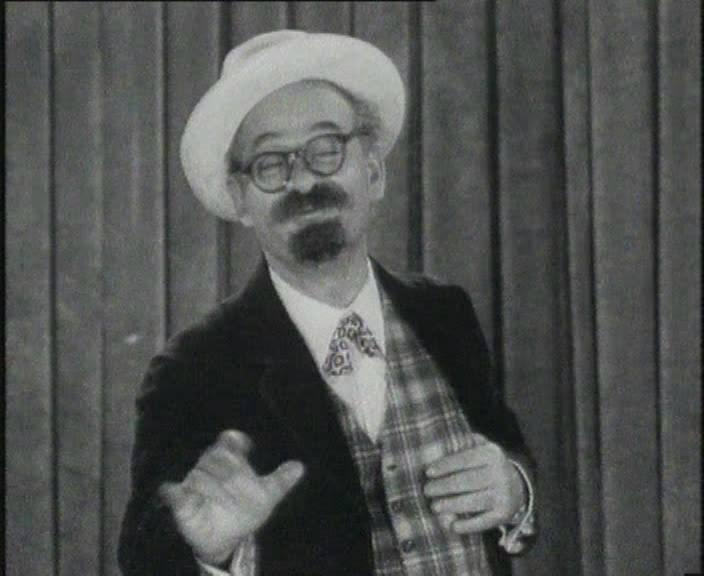

I filmed Zagarnar secretly in 2007 for a documentary on freedom of expression at a time when he was facing total censorship. We discussed how he became a comedian, how his fame led him to perform for the former dictator Ne Win. He told me how on his fourth jail sentence he survived five years of solitary confinement.

This footage remained unused. So when, two years later, I heard that he had been sentenced to 59 years in prison, on trumped up charges, I made a film that highlighted this injustice in the hope that I could galavanise people to put pressure on the regime to release him.

In this program for Radio 4, I return to Burma to interview Zagarnar again, contrasting his freedom now with the threat he talks about in my original recordings.

It was also to witness his first major show since his imprisonment, to hear him teaching comedy, to observe how far he will push the new regime to implement the promises of democracy and the price he and his family have paid.

Zaganar is Burma’s greatest living comedian but he is also much more than that. As a political activist, he was a fierce critic of Burma’s Generals who put him in jail several times, including 5 years in solitary confinement, for exposing their crimes and human rights violations.

I secretly interviewed Zarganar in Burma in 2007 for An Independent Mind, my feature documentary about freedom of expression. At the time Zarganar was totally banned from any artistic activity. In 2008, he was arrested again and sentenced to 59 years in prison, later reduced to 35 years for giving interviews to the foreign media about the desperate situation of hundreds of thousands of people made homeless by Cyclone Nargis.

In 2010, I secretly visited Burma again to make a new documentary about Zaganar’s imprisonment. Our film, ‘This Prison Where I Live’ was as much about a country living in abject fear as it was about Zaganar himself.

After a world wide campaign, Zaganar was finally released in 2011 during an amnesty of political prisoners following elections and a series of ‘reforms’ moving to a military backed civilian government. I then traveled openly to Burma to interview Zaganar in his home country for the first time since his release.

Arriving just after the recent sectarian violence between Buddhists and Muslims in Meitila, I heard how Zaganar was trying to mediate between the two sides. I learnt that the comedian had also been part of a commission looking at the violence and displacement of thousands of people in the western state of Rakhine.

Zaganar talked to me about continuing as an artist in Myanmar, about performing anyeint, a traditional form of theatre combining dance, music and comedy, even though he was working with a government containing people that imprisoned and tortured him.

Zaganar, which means “tweezers”, continues to use his unique satire to speak out as the country moves along a deeply uncertain path to democracy.

Presenter: Rex Bloomstein

Producers: Simon Jacobs & Rex Bloomstein

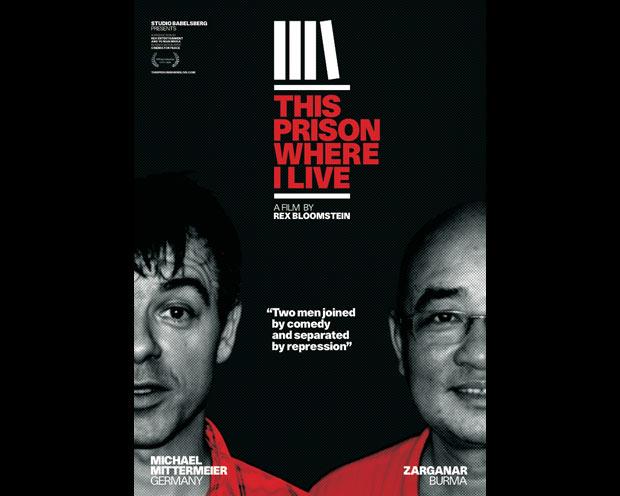

We decided to re-edit the end of the film because of the great news of Zarganar’s release from jail in late 2011. We all met in London in 2012 and filmed our encounter. This then became the basis of this new version, which is now 75 minutes long.

On completing This Prison Where I Live in mid-2010 we joined with several NGOs and human rights groups to form the Free Zarganar Campaign. As part of this campaign, the film was screened in more than 30 different countries over the course of the following 12 months.

But Burma was beginning to change. The ruling military elite was edging tentatively towards democracy and, on 12th October 2011, we were finally able to celebrate as Zarganar became one of the first political prisoners to be released. This was six weeks after the Democratic Voice of Burma broadcast the film illegally into the country on its satellite channel.

A few months later he was allowed to leave the country to be reunited with his family in the US. And then he came to Britain.

We were waiting.

The updated version of This Prison Where I Live is a slightly tighter, 75-minute cut, which includes six minutes of new footage filmed on the day Michael Mittermeier and I caught up with Zarganar in London. For Michael, it was a first meeting with a man he had admired from afar, but thought he may never see in person.

Zarganar told us how he had watched a copy of This Prison Where I Live smuggled into prison before his release and revealed that Burma’s president, Thein Sein, had also watched the film - and, bizarrely, said he liked it! Zarganar felt the broadcast of the film was a significant factor in hastening his release.

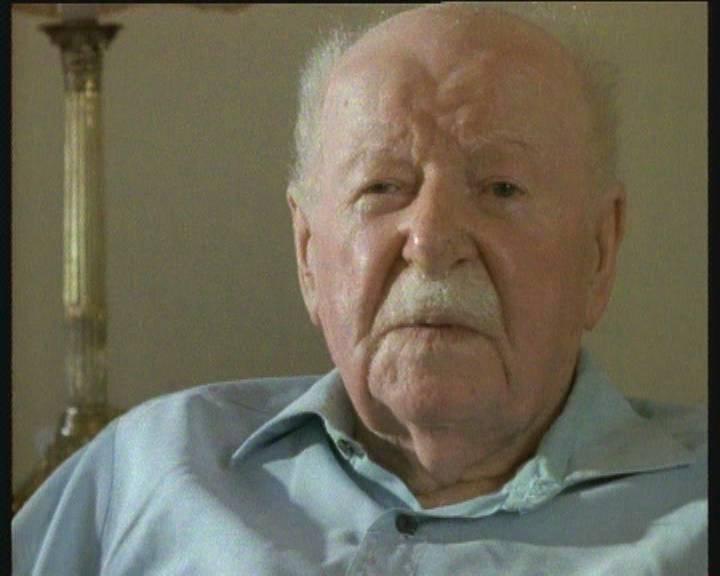

Dying Inside was my first documentary for radio and explored the growing phenomenon of older prisoners in our prisons, hearing at first hand from those who face the prospect of getting aging behind bars.

This country has the largest prison population in Europe with over 80,000 inmates costing the taxpayer on average £45,000 per year per prisoner. The fastest growing group within it are older prisoners, who number over 8000. This is largely due to sentences becoming longer.

At present there is no national strategy to deal with this issue. Prisons cope as best they can. Inmates are classed as older prisoners from the age of 50 when they are more likely to suffer with diabetes or coronary heart disease or have problems with their mobility.

For this first ever broadcast programme on the subject on British radio or television, Rex Bloomstein visited three prisons: HMP Maidstone, HMP Whatton and to the Elderly Lifer Unit at HMP Norwich, the first time that anyone from the media had been allowed in.

The programme revealed one of the more extraordinary aspects of this story, namely that over 40% of older prisoners are men convicted of sexual offences. An increasing number of them committed their crimes many years ago, but have been caught by advances in DNA techniques.

At the heart of this documentary is the testimony of the prisoners themselves, some of whom have been incarcerated for many years, while others have been sentenced late in life after their past caught up with them. Several have very serious health problems and face the possibility of ending their days behind bars – in fact dying inside.

Presenter: Rex Bloomstein

Producers: Rex Bloomstein & Simon Jacobs

A Unique Production for BBC Radio 4

“I never realised until I came into prison what the term ‘doing time’ meant. I’ve been marking time now for almost 30 years – ticking the days, months and then years off…I increasingly feel I am slowly dying away, ‘dead man walking’ as the saying goes.”

I read about David, an 82, year old man with terminal cancer. But unlike most men his ‘family’ are prison officers, care workers and fellow prisoners. David is serving a life sentence and will almost certainly die inside. I then discovered that the fastest growing age group in our jails are older prisoners.

In 2015 there were almost 12,000 men aged over 50 – four thousand of them more than 60 – one hundred more than 80 and five over 90. There are more than 300 women aged over 50 in prison in England and Wales. Almost 500 are over 70 years of age.

Today 16% of the prison population are aged 50 or over—13,636 people.

I became aware that these facts are creating huge challenges for prison, probation, health and social service staff within the system. Even more disturbingly, older people in prison are subject to discrimination and isolation, often eking out an existence on the wings and landings in our Victorian jails as well as our modern ones.

Dying Inside came to be the first documentary to investigate this subject for radio.

Many older prisoners are finding life in prison a kind of hell. Those unable to work, exist on a prison pension of £3.25 per week; they tell of being bullied and intimidated by the increasing number of younger drug addicted prisoners coming into jails. For those older prisoners who can be released, resettlement can seem terrifying in the face of the enormous challenges readjusting to the outside world. Some simply can’t hack it and remaining institutionalized is the only option:

The truth is that the aging process for older prisoner accelerates - 60 year olds have the bodies of 70 year olds. Many prisoners face the prospect of never leaving prison alive whilst many of these older offenders are literally dying inside.

So should we care? A number of these people have committed very serious crimes: murder, sexual offences. Many would say they deserve whatever they get, whatever they endure and should not be released. That view, lets call it the Daily Mail one, has certainly had its impact, especially through the New Labour years. There are now more people serving indeterminate life sentences in the UK than in all other 46 countries in the EU put together.

What is also clear is that there is no national strategy to deal with older offenders. Apart from HMP Norwich there is no hospital/hospice facility for the terminally ill within the prison system. Age Concern launched an Older People in Prison Forum in 2005, its local branches are piloting schemes while the National Offender Management Service is doing work in prisons such as HMP Whatton but admit not enough governors are doing the same.

There’s no policy framework because because no government wants to appear soft on crime and the criminal.

Longer and harsher sentencing, combined with an overall trend of an ageing population in the UK, has caused this warehousing of many more people than ever before. But is it sustainable? In purely economic terms, it’s costing a fortune in taxpayer revenue. Further concerns are the impact of overcrowding and scarce resources on the needs of older prisoners coupled with the Prison Service and the Parole Board being increasingly wary, even frightened, of taking the necessary risk to release people. The result has been many older prisoners staying beyond their tariffs.

The NHS now has the responsibility for healthcare in our prisons but only some of them have specialist services for older people. It appears that the needs of the frail and the sick prisoner are often largely unmet. For those terminally ill within the prison system – the lack of palliative care is a major concern because so many prison staff lack specialist training.

My aim was to build this programme principally around the testimony of older prisoners (principally in their 70s & 80s), illuminating the issues outlined above and exposing what will become a major concern in the years ahead. I wanted to ask what can we learn from their experience? What does the way we treat older offenders say about us and the prison system that contains them? What does it say about the nature of redemption, forgiveness, the need to punish and our respect for human rights?

Access

One of the main issues of course was access. Would we be allowed to conduct interviews and explore what it is like to be an older prisoner? The answer in principle was yes and agreement reached with the MOJ.

Further Facts

Older prisoners can be split into four main profiles, each with different needs:

Repeat prisoners. People in and out of prison for less serious offences and have returned to prison at an older age.

Grown old in prison. People sentenced for a long sentence prior to the age of 50 and have grown old in prison.

Short-term, first-time prisoners. People sentenced to prison for the first time for a short sentence.

Long-term, first-time prisoners. People sentenced to prison for the first time for a long sentence, possibly for historic sexual or violent offences.

Many experience chronic health problems prior to or during imprisonment as a result of poverty, poor diet, inadequate access to healthcare, alcoholism, smoking or other substance abuse. The psychological strains of prison life can further accelerate the ageing process.

The Prison Reform Trust, along with HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, the Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, Age UK and other organisations have called for a national strategy for work with older people in prison, something the Justice Committee agreed with and has stated: “It is inconsistent for the Ministry of Justice to recognise both the growth in the older prisoner population and the severity of their needs and not to articulate a strategy to properly account for this.”

The Care Act means that local authorities now have a duty to assess and give care and support to people who meet the threshold for care and are in prisons and probation hostels in their area.

With prison sentences getting longer, people are growing old behind bars. People aged 60 and over are the fastest growing age group in the prison estate. There are now more than triple the number there were 16 years ago.

Despite the significant rise in the number of over 50s in prison in recent years, the government projects only a modest rise in their numbers by 2022—14,100 people, an increase of 3%. The most significant change is anticipated in the over 70s, projected to rise by 19%.

45% of men in prison aged over 50 have been convicted of sex offences. The next highest offence category is violence against the person (23%) followed by drug offences (9%).137

234 people in prison were aged 80 or over as of 31 December 2016. 219 were in their 80s, 14 were in their 90s, and at the time of writing one was over 100 years old—87% were in prison for sexual offences.

Sony Award - Winner: Silver

Rex Bloomstein - Presenter/Producer

Simon Jacobs - Producer

Laura Parfitt - Executive Producer

Chris O’Shaughnessy - Sound Engineer

Philippa Geering - Broadcast Assistant

Unique The Production Company for BBC Radio 4

What the Judges said:

This was a remarkably strong documentary that confronted preconceptions, was thought-provoking and had moments of surprise. It was beautifully crafted and its eloquent silences sometimes spoke louder than words. The judges were impressed with how its calm, insightful interviewing style brought out fascinating, sometimes moving stories from people we rarely hear from, let alone think about.

The Observer, Miranda Sawyer

First, Dying Inside, about elderly prisoners. As our sentences get ever harsher and people are put away for longer, and as DNA techniques improve, meaning old crimes can be solved, our prison population is getting older. But Britain has no national strategy for older prisoners. Rex Bloomstein visited three prisons that contain inmates of 50 years or older. Such as Daniel, 65, who’d committed rape in 1982. More than 40% of older prisoners are people convicted of sex offences. “You do think about your crime,” said Daniel. “For 24 years I lived in a nightmare.” You wondered about his victim, whether their nightmare ever ended.

We heard, too, from Gerry, 69, who talked about his retirement. “I did my sport, I did my antiques, I did places I wanted to go that I couldn’t when I was at work. There was only one thing missing,” he said evenly, “and that was sex.” Your heart stilled, just for a second.

This documentary pulled you all over the place. It made me cry, and I’m still not sure who for. How to feel about Tommy, who was on his 24th year of a life sentence for murder? “It’s always there at the back of your mind. You’ll be eating and it puts you off your food. I knew the victim. He was a good friend of mine.” Tommy was in the UK’s only specialist unit for old (and very ill) prisoners, in Norwich. God’s waiting room, he called it. He’d seen 22 inmates die in the past four years. “I’m waiting on the wind to blow me one way or the other,” he said. Where will it blow you? asked Bloomstein. “To hell, I suppose,” said Tommy.

The Telegraph, Gillian Reynolds

The most thoughtful documentary of the week was Rex Bloomstein’s Dying Inside (Radio 4, Tuesday). Bloomstein usually makes TV documentary films. Radio suits him. This programme was about the large and growing segment of the prison population over 50, the age at which conditions of older life – diabetes, heart disease, arthritis – set in. The prisoners he spoke to were mostly serving long sentences for offences they either admitted (arson) or we were left to deduce (paedophilia). The interviews were clear, fair, courteous but left behind big streaks of doubt. One man confessed his offences, grievously penitent. Another, in a wheelchair, wanted to go home to babysit for his family. The listener was left to weigh what they said against the probability and the desirability of either, ever, being at liberty again.

This is a film about two comedians.

Zarganar is Burma’s greatest living comic. Relentlessly victimised by the military junta, in 2008 he was sentenced to 35 years in prison – silenced for his outspoken criticism of the ruling generals. Michael Mittermeier, in stark contrast, is free to practise as one of Germany’s leading stand up comedians.

Two men joined by comedy and separated by repression.

The genesis of this film begins in 2007, when Zarganar agreed to be interviewed by documentary filmmaker, Rex Bloomstein, despite being banned from all forms of artistic activity and talking to foreign media. Over two days Bloomstein and his team interviewed Zarganar in depth in his flat, and were shown the cinemas that are prevented from screening his films, the bookstalls not allowed to sell his plays or poetry, and the makeshift TV studio where his fellow comedians rehearse on a stage that he himself is forbidden to tread.

Hearing of Zarganar’s fate and seeing this footage, Michael Mittermeier joined with Rex Bloomstein to make a film about this courageous man, who has paid such a price for speaking out against the regime. Together with a small team, they travelled secretly to Burma in 2010 to document his struggle against repression and to investigate humour under dictatorship.

This Prison Where I Live is a feature documentary and is the story of Michael’s exploration into the personality, the motivation and the talent of a man who describes himself as the ‘loudspeaker’ for his people.

I arrived in Rangoon, the former capital of Burma, in April 2007 to begin a journey to Mandalay for An Independent Mind, my feature documentary on the struggle for freedom of expression in different parts of the world.

Before we left to travel north, our contacts had arranged for us to film a man who was banned from producing, directing or acting, banned from any performance on stage, banned from talking to any foreign media, banned from writing in any journal or magazine; the very mention of his name totally forbidden.

It was Zarganar, Burma’s leading comedian.

We secretly filmed this extraordinary man for two days – at great risk to himself. This footage remained unused. So when, two years later, I heard that he had been sentenced to 35 years in prison, I was determined to make a film that would reveal this wonderful comic personality. A film that would share, as I had shared, his thoughts and feelings, his stories of arrest and torture, how he had survived five years of solitary confinement. I wanted the world to experience his humility, his identification with the ordinary people of Burma and his fearless opposition to the Generals. I also wanted people to hear his response to the years of persecution he had suffered at their hands, when he turned to me on camera and said, “my enemy must be my friend.”

It was the great German comedian, Michael Mittermeier, who made this film possible. I decided to tell the story of how it came into being and the decision Michael and I made to go to Burma. We wanted to get as near to Zarganar as we possibly could and show the world the prison he was in. But it was also important to reveal the problems we encountered, the questions we had to ask ourselves about what we were doing, and why, and what harm might befall both us and the people who were helping us. It was they who had to live and survive day by day in a dictatorship. It is all there in the film along with excerpts from Zarganar’s movies and television appearances that we managed to smuggle out of the country.

Rex Bloomstein

“Maung Thura, better known as Zarganar, is considered to be Burma’s greatest comic. His outspoken opposition to the country’s military junta has led to 25 years imprisonment on the flimsiest of charges. The film contrasts the price he has paid for his role as the ‘loudspeaker’ for his people with the freedom of speech enjoyed by controversial German satirist Michael Mittermeier. A lengthy 2007 interview with Zarganar is at the heart of this thought-provoking documentary about state repression.” - THE DAILY EXPRESS, 4 stars

“A long prison sentence, we now know, can win you a Nobel Peace Prize. In nations light on human rights – whether China or in This Prison Where I Live, Burma – it can also win you a quixotic, captivating documentary. The poet and stand-up comic Zarganar, after years of satirising the military junta and after one previous jail spell, is now serving a 59-year sentence for treason. British filmmaker Rex Bloomstein logged an interview with him just before he was sent down and uses snippets as an extended prologue. The burly baldpate cracks jokes like hard-boiled eggs, while fully aware (we sense) that he may be the next egg to be cracked by fate.

The rest of the film narrates Bloomstein’s return to Burma, with German stand-up comedian and Zarganar fan Michael Mittermeier (who also produced the film) as a frontman. The focus is a bit muddled. The field trip’s programme starts falling through when Zarganar’s friends fail to honour interview appointments. (The junta has warned them off.) Finally – yet compellingly – Bloomstein and Mittermeier are reduced to contraband camerawork, taking drive-by shots of Zarganar’s prison from car and motorbike.

Are they in peril of arrest? Probably not. But these scenes stir some much-needed “action” into a film Beckettian, at times, with inanition. Waiting for Zarganar. Or perhaps, in weird kinship with wannabe biographer Ian Hamilton’s famous Salinger hunt, In Search of Zarganar. It’s a charming, courageous film even at its most maddening. Fittingly it ends with the appalling postscript – a parody of optimism fit for a military state – that Zarganar’s sentence has now been ‘reduced’ to 35 years.” - THE FINANCIAL TIMES

“[Zarganar is] probably the bravest comedian in the world. In the film, which features rare footage of him in conversation, he comes across as the humblest, too. Prevented from earning a living or even writing his own name, he explains, with smiling certainty, that it’s all part of the job description: ‘We must stand in front of the people – and sacrifice for the people’, he says’.” - THE DAILY TELEGRAPH, Dominic Cavendish

“Burmese comedian and film director Zarganar is currently serving a 35-year prison sentence for daring to criticise his country’s military dictatorship. This inspirational but somewhat meandering documentary melds the footage of British film-maker Rex Bloomstein, who interviewed Zarganar in 2007, with the story of a German comedian, Michael Mittermieier. They travelled together to Burma to secretly film an investigation into a humble, jovial but ferociously courageous figure. Although overlong and drifting, this film will make you seriously question whether you would stand up to injustice if the stakes were this high.” - METRO

“This Prison Where I Live is an eye-opening documentary about Zarganar, a Burmese comedian who director Rex Bloomstein met a couple of years ago in the authoritartian state. A mischievous, indomitable critic of the brutal military leadership, Zarganar was last year imprisoned for more than 50 years for making some mildly disparaging remarks about the regime to foreign press. Attempting to discover what exactly has happened to Zarganar, Bloomstein returns to Burma with Michael Mittermeier, a successful German comedian (yes, they do exist). What unravels is a damning portrait of the extent of state censorship – no one will speak to Bloomstein, fearful of the repercussions – and a fierce indictment of a society that is compelled to lock up its comedians. There’s plenty of archive footage of Zarganar, and while his humour struggles to transcend cultural barriers, his impish and jovial presence lights up the screen.” - THE BIG ISSUE

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Article 19

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

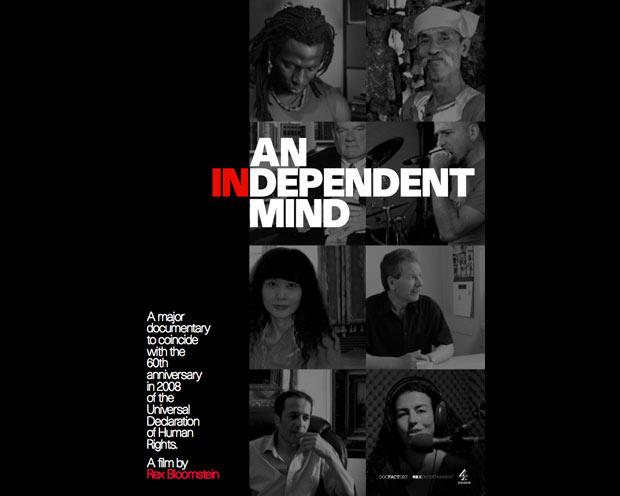

How do you deal with the threat of imprisonment for drawing a cartoon of your president? How do you survive being sent to a labour camp for telling a joke? What is the impact of being tortured for writing a poem? Or of being forced into exile for singing a song?

These are some of the stories you will encounter in AN INDEPENDENT MIND, a unique feature-length documentary inspired by one of the most fundamental and controversial of human rights: Freedom of Expression.

Through encounters with a succession of eight different characters attempting to exercise their right to freely express themselves in different parts of the world, the film explores in human terms the importance and complexities of freedom of expression and its acceptable limits. Eight individual voices that together magnify one profound central theme.

Above all, it is a film that will make you reflect – on the importance of the free dissemination of knowledge, opinion, art and, significantly, its limits.

From a research list of well over a hundred different cases from all over the world I chose eight different characters. These stories follow one from another. They are not inter-cut, each is self-contained and each character speaks for themselves. There is no commentary. I have endeavoured to be non-judgmental, to present each individual to the audience as they presented themselves to me.

Freedom of expression is a cornerstone right but it is not an absolute right. Under international law, it is subject to restrictions on certain grounds, such as national security, morality, protection of an individual’s reputation, or incitement to violence.

But these limits and restrictions are rarely clear-cut. How are they defined? How open to abuse are they? Should freedom of expression include the freedom to say unpopular things? Is freedom of expression a luxury in the modern world?

Through AN INDEPENDENT MIND I want to encourage our audience to reflect on these questions by seeing people who are actually dealing with the consequences of living their lives as artists and thinkers. This is a film that allows us to glimpse their realities as people who are exploring, confronting and commenting on their societies. Through them, I hope we can reflect on the importance of freedom of expression, its complexities and challenges and limits.

I wanted this to be as global an exercise as possible. It would have been easy to focus on certain parts of the developing world, while ignoring our own Western democracies. But we are also seeing a gradual erosion of this freedom in the West through the broadening in scope of what is deemed ‘unacceptable speech’.

This is an age of extraordinary mass communication, when all the different forms of modern media should, on the face of it, be giving an opportunity for anybody to freely express themselves, yet Article 19 seems to be an area that is increasingly bitterly contested.

AN INDEPENDENT MIND is a film for our time.

Rex Bloomstein

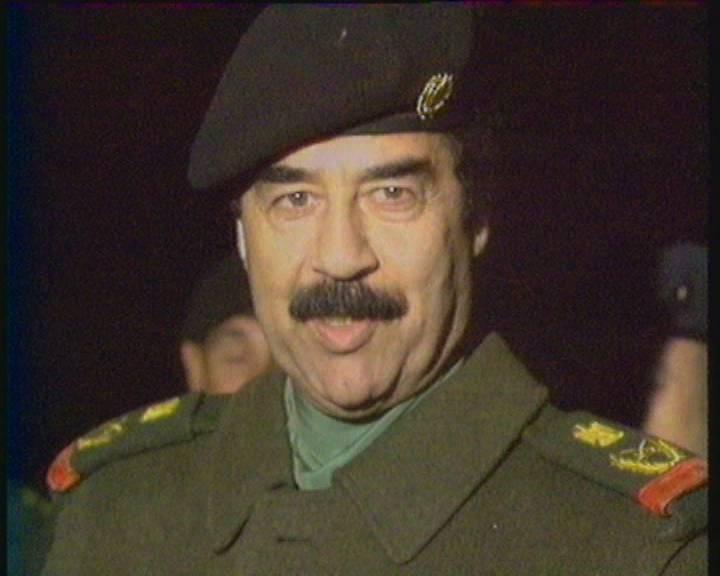

“This Wednesday, it will be 50 years since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly. On the eve of that anniversary, Rex Bloomstein’s new documentary, An Independent Mind, follows eight very different people from around the world as they fight for their freedom of expression.

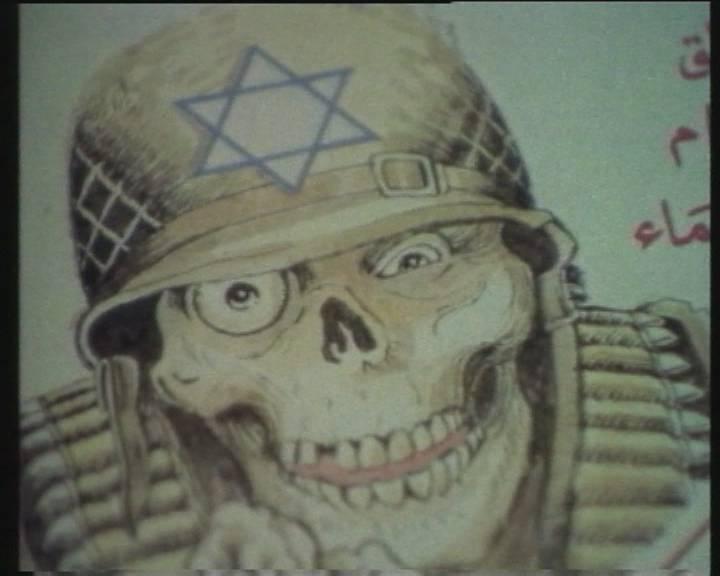

The subjects range from the exiled Ivory Coast singer Tiken Jah Fakoly to the Chinese sex-blogger Mu Zimei; from Burma’s political comedians the Moustache Brothers to the British historian David Irving, who has been accused of being a Holocaust denier in the past. Others include a Basque rock group, a Syrian writer and an Algerian cartoonist, all of whom have been imprisoned or silenced due to their beliefs. ‘These people are living with the consequences of their choice to speak,” says Bloomstein. ‘Through these lives, I hope that we will have a strong sense of just how vital that freedom is and the price that others will pay for it.’

Bloomstein’s film is unsettling. With no narrator to guide you or music to distract you, the stories speak for themselves, with often surprising consequences. David Irving, for example, who has written admiringly of Hitler, makes a convincing case against censorship. ‘He was very interesting indeed,’ says Bloomstein. ‘Being Jewish myself, my decision to include Irving could be seen as controversial. But I’m not supping with the Devil. I’m exploring someone who has often repellent views. Irving denies he’s a denier. Nevertheless, should he have been imprisoned? I’m not sure that he should. I happen to favour debate and challenging people like Irving.’

The director concedes, however, that ‘freedom of expression by itself cannot be unlimited. There should be a marketplace for ideas. The health of society is often determined by the width and breadth of opinions and the explorations that are available. And if people feel offended or threatened, then they must turn to the law’.

In the past, the director has won awards for his unflinching films about prisons and the Holocaust (including KZ and Kids Behind Bars). An Independent Mind is a similarly stirring, challenging piece of work. ‘I’m hoping that it will make people think about what society would be like without freedom of expression. It is a vital human right, and without it, we’re much diminished.’” – THE INDEPENDENT ON SUNDAY

“Rex Bloomstein’s thoughtful, subtle film asks what has become of one of the defining questions of our time… Excellent.” - GUARDIAN GUIDE

“Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that “everyone has the right to freedom of expression” and it’s this that drives Rex Bloomstein’s sober and reflective documentary…..Bloomstein believes that that those that seek to defend freedom of expression should do so in all quarters, however unpalatable the sentiments.” – THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

“’As soon as you start saying this opinion is accepted and acceptable and that opinion is not acceptable, then you are degrading society’. A laudable closing statement for this meaty film… “ – THE TIMES, DIGITAL CHOICE

“Marking the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Rex Bloomstein’s film raises issues of freedom of speech by letting various individuals relate their battle to express themselves.” – THE OBSERVER, DIGITAL PICK OF THE DAY

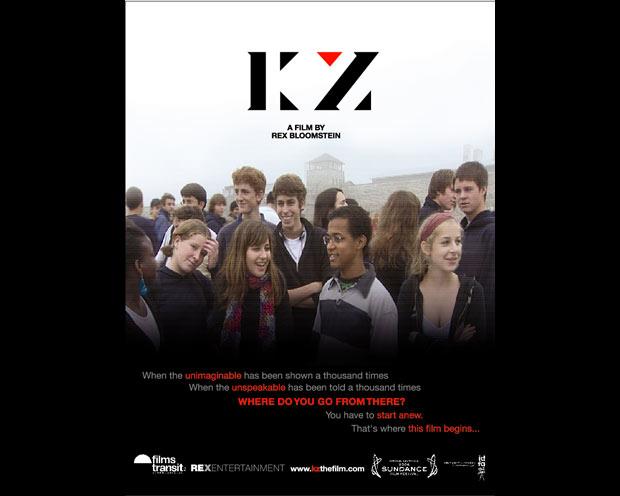

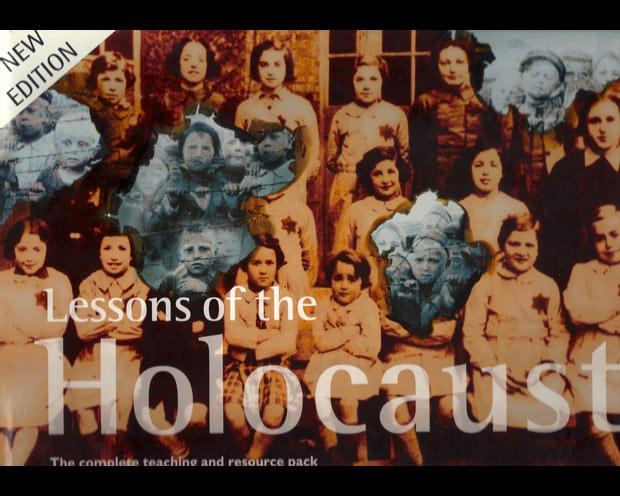

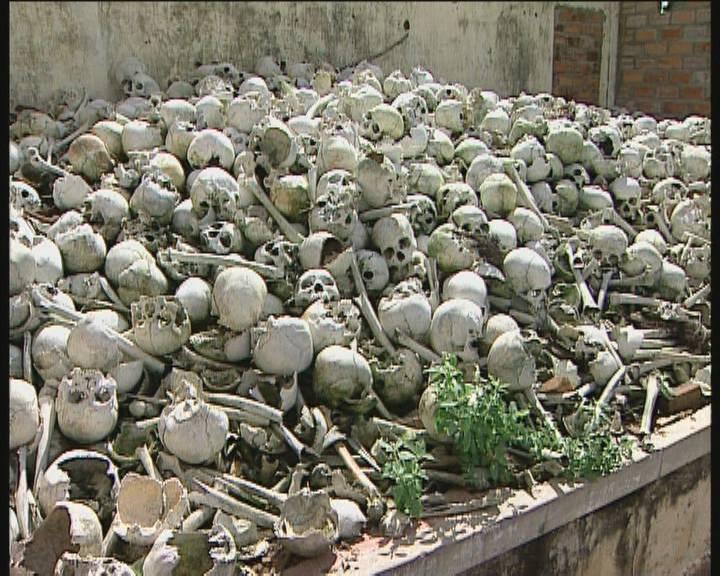

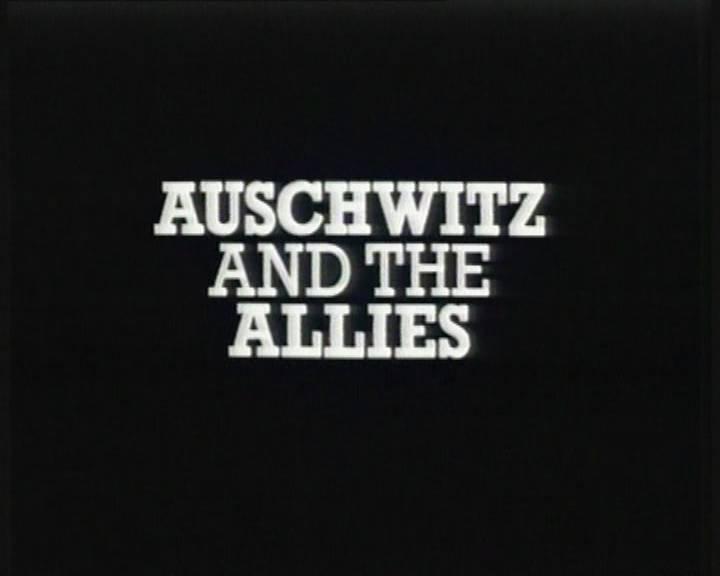

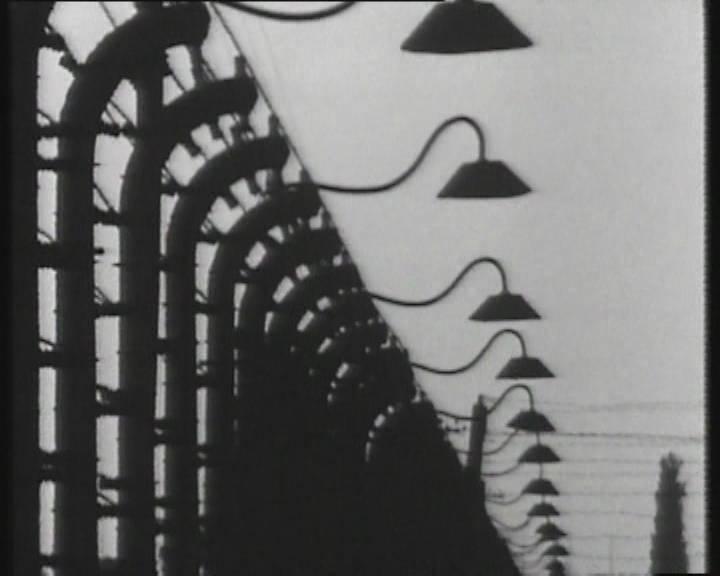

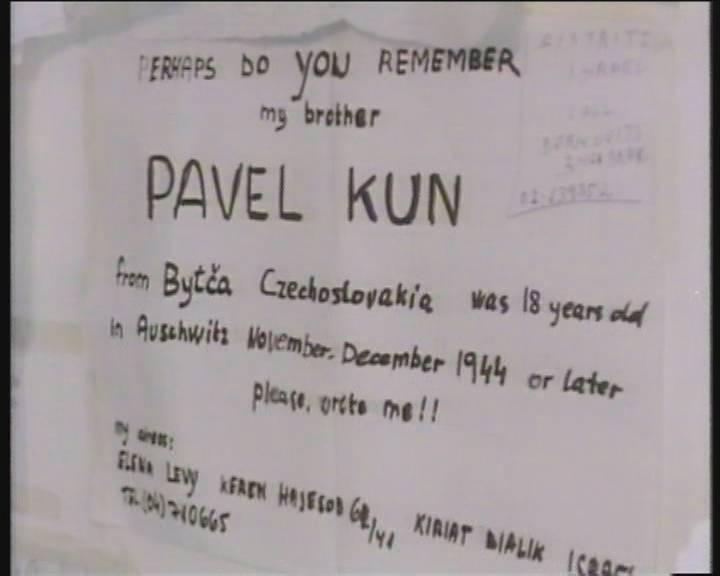

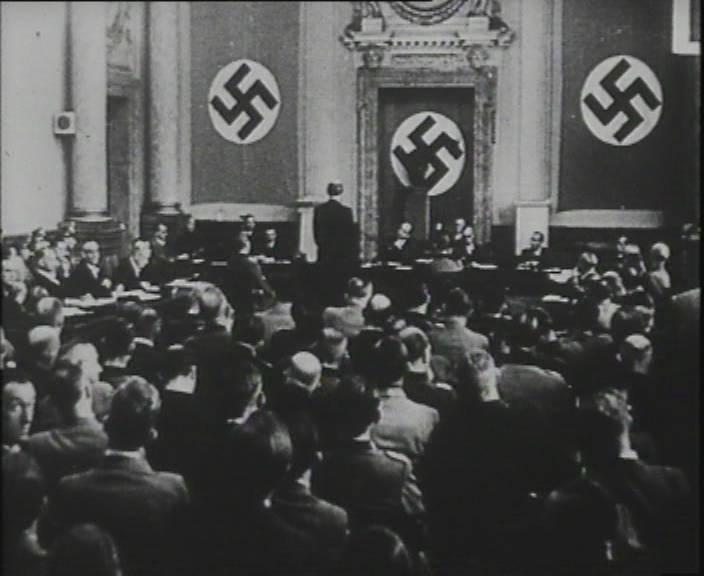

When the story of the unspeakable has been told a thousand times, when the images of the unimaginable have been shown a thousand times, when the mind is numb – where do you go from there? You have to start anew…

That is where this film begins.

On the banks of the river Danube, surrounded by the beautiful landscape of Upper Austria, lies the picturesque town of Mauthausen. Two kilometers from its town centre is a place that attracts bikers, busloads of tourists, parties of schoolchildren, people from all over the world. Tour guides come to work here every day, while nearby the locals go about their daily lives. This is a place where thousands upon thousands of people from over 30 nations were tortured and murdered. This site is the former KZ, German short for concentration camp. How does it feel to be a tourist at a former concentration camp?

How does it feel to work here as a guide, day in day out? How does it feel to live here as a local with the dark secrets of the past? And what of those who’ve chosen this town to be their new home?

This is a groundbreaking film about facing our ultimate demons. It is a contemporary yet timeless piece on the horrors that we have and always will be able to inflict on one another.

Stripped of the usual dramatic devices, survivor testimonies and archive footage this radical film shows nothing but says everything.

It will shake you to the core.

The oompah band played. Sausage and beer flowed. The men and women in lederhosen danced and sang. We’d broken for lunch and had stumbled across this typical pub party in rural Austria. Having eaten, we walked back some 400 hundred yards to the quarry in which we were filming - the main quarry where so many prisoners had been systematically worked to death only sixty years before. This was Mauthausen. It was 1995 and I had been making a film about the liberators of the Nazi concentration camps.

The disjunction of those two scenes remained with me – the carefree laughter of the pub garden and, a short walk away, the silence of the quarry.

Countless documentaries about the Holocaust have been made since the revelations sixty years ago of Auschwitz, Dachau, Belsen and Sobibor. There is talk of ‘Holocaust fatigue’ as if such a subject can ever be exhausted. What is true is that successive generations must find their own way to deal with the ‘tremendum’, as one philosopher has named it. For many questions continue to haunt any endeavor to understand the essence of the concentration camps. What are our reactions at the horror that engulfed millions? How can we respond to the incredible plan to obliterate every last Jewish man, woman and child from the face of the earth and dehumanize and enslave whole other races and groups of people?

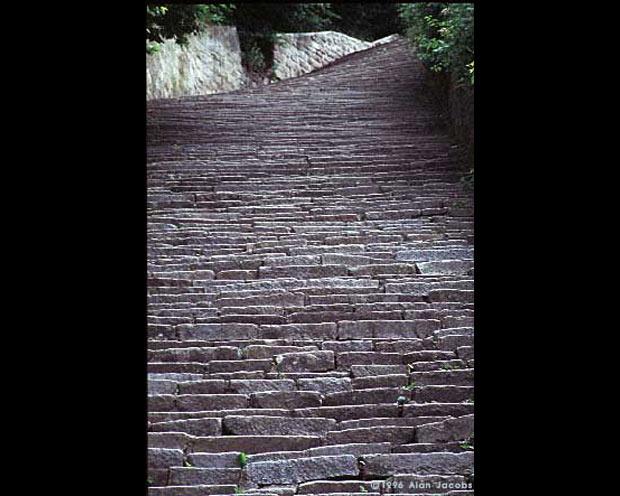

Today thousands of people come from all over the world to visit Mauthausen, the largest Nazi concentration camp in Austria. Curious and compelled by what took place 60 years ago, they walk through the concrete buildings where the SS administered the camp, the inmate blocks that housed prisoners from all over Europe as well as American, British and Russian POW’s, the gas chamber and crematorium, the execution corner. They clamber up the 186 steps that prisoners were forced to climb with knapsacks full of bricks from the quarry.

What do they think?

What do they feel?

What are their questions?

This is our focus: the tourists, the sightseers, the curious wandering about the camp; those who have come specifically; the tour guides leading groups of school children and parties of older people; Mauthauseners going about their daily lives; Mauthauseners who were young at the time; and those who have become Mauthauseners by deciding to move to the area.

As the project developed I realized that the film had to be more austere in its approach and that I would have to jettison most of the fashionable tools of documentary filmmaking. So there is no commentary, no music, and no reconstructions with actors.

KZ is stripped down. There is no attempt to sentimentalize or overtly manipulate the emotions. There are no historians; there is no black and white footage of the liberation of the camp, no piles of corpses. All have been seen. It is in the reactions of the guides, the visitors, young and old, that the challenge lies. It is in the universality of that experience.

KZ is probably the first 21st century film on the Holocaust without survivors and as such it presages the future.

KZ is a film about the interface between now and then. What do the meanings of the camp experience convey to all of us who were never there? How possible is it for our imagination to grasp the enormity of the crimes committed there. Why should we consider these events when we have our own contemporary genocides and wars?

KZ is a film that it is set in the landscape of a concentration camp but is a film about today, a film about us.

What will we remember?

In the Gulag Archipelago, Alexander Solzhenitsen wrote “If only there were evil people somewhere, insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?”

Rex Bloomstein

“Documentaries about the Holocaust tend to draw heavily on survivor testimony and archive footage in a doomed attempt to convey the ineffable, the most celebrated being Claude Lanzmann’s ‘Shoah’. With KZ, director Rex Bloomstein adopts a different approach, creating something quietly insightful and unsettling. While shooting an earlier film in the Austrian village of Mauthausen, site of a former concentration camp now refashioned into a grim tourist attraction, Bloomstein was struck by the contrast between the gruesome reality of the camp and the neighbouring village idyll. KZ explores how people live and cope with an historical trauma that occurred on their doorsteps, and their capacity to learn from those events.

Such toxic subject matter inevitable produces disquieting moments. As the camera tracks several guided tours through the camp, neither they nor the viewer is spared any of the details of what happened there by the zealous tour guides (one girl is so disturbed she faints). The tension peaks in the gas chamber, where a commemorative plaque has been defaced with a swastika. Throughout these claustrophobic sequences, Bloomstein trains his camera closely and almost exclusively on the shell-shocked visitors’ faces, which in turn compels the viewer to examine their own responses. Outdoors, the wind-strafed camp is absorbed in long takes, which build an effectively brooding atmosphere. Emergent visitors proffer many motives for their visit, ranging from religious empathy down to box-ticking on a tourist schedule. “It’s very nice here,’ enthuses one, who looks forward to visiting Auschwitz the following year.

These scenes are delicately crosscut with footage filmed in the local village, where interviewees’ responses are more varied and complex. A young couple evince little concern about living in a house once owned by an SS officer who worked at the camp, regarding it simply as a piece of prime real estate. An elderly man waxes nostalgic about the ‘beautiful time’ he had in the Hitler Youth. One elderly woman recounts the ‘beautiful wedding’ she attended in the camp. Not all the village elders are so insensitive, but the general tight-lipped reluctance to dwell on the past builds and overriding impression of denial, willed amnesia or indifference.

As Bloomstein roves the village his camera alights on fascinating details. The McDonald’s logo next to the sign directing the way to the camp is ….

… of course, Austrian himself, and he fetished exactly this brand of twee, folksy culture into a major plank of Nazi ideology. Austria, however, has never really admitted its culpability for Nazi-era war crimes, preferring to see itself as a victim.

That sense of denial is surely one aspect of what motivates the tour guides. All of them had grandfathers in the SS; there’s a strong sense of expiating a lingering sin. The most wracked figure is an alcoholic, whose marriage is breaking down partly because all he talks and thinks about is the camp. Clearly such sensitivity and openness to the past can be dangerous on a personal level. ‘We’re all sick up here,’ the man concludes. In the most resonant scene, Bloomstein shadows him as he does his round of the camp at closing time, just as dusk is falling, and tunes into an atmosphere of palpable dread. At such moments the camp seems like the psychic equivalent of a nuclear reactor, radiating its negative influence across generations and still capable of wreaking enormous damage on individual lives. Bloomstein’s film carefully marshals a polyphony of responses to the camp’s disfiguring presence, and the stark aesthetic - there is no music, narrative commentary or ‘expert’ testimony - feels entirely of a piece with the film’s refusal to pass judgement or draw conclusions. KZ is a beautifully understated, troubling achievement, one haunted by the necessary burden as well as the limits of memorialisation.” – SIGHT AND SOUND , Kieron Corless

“In its deceptively calm way, KZ is the year’s most fascinating documentary.” – THE INDEPENDENT ON SUNDAY

“KZ…is an outstanding documentary.” – THE OBSERVER

“…it raises issues of remembrance, and forgetting in a steadily unsettling, powerfully understated way.” – THE TIMES, 4 stars

“Rex Bloomstein achieves the impressive feat of not merely memorialising the Holocaust, but probing the complex, discomfiting hold it continues to have on the now.” – TIME OUT, 4 stars

“If it weren’t true you simply wouldn’t believe it…an impressively calm documentary.” – EVENING STANDARD, 4 stars

“Rex Bloomstein’s powerful documentary about the WW2 Nazi Mauthausen concentration camp centres on guides taking tourists around the camp (there is no archive footage), and his stark account still chills to the bone.” – THE DAILY STAR

“Britain Shines at Sundance”

“KZ ambitiously aims to create a radically different Holocaust film….. admirable work.” – THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

“Sundance Film Festival”

“quietly electrifying…. KZ reinvigorates oft-told Holocaust atrocities by relaying them from neglected perspectives.” – NEWSDAY

“Subtle and understated - but this only serves to make the film all the more unsettling.” – SCREEN INTERNATIONAL

“Committed Brit docu-helmer Rex Bloomstein continues his career long engagement with … KZ … increasingly disturbing portrait of contempo guides and visitors at the Nazi concentration camp Mauthausen, and villagers in the Austrian town. Strong subject and unfussy execution … Tech package is pro … Overlapping sound subtly knits together disparate scenes to impressive fluency and narrative flow.” – VARIETY

“Sublime … KZ becomes a fascinating study of the way minds work when confronted with the inconceivable.” – SALT LAKE WEEKLY, 3 ½ stars: favourable

“KZ is a totally engrossing and extremely disturbing doc….a powerful message delivered in an intriguing way.” – FILMTHREAT.COM, 4 stars: highly favourable

Critic’s Diary: “Rex Bloomstein’s powerfully restrained KZ makes a compelling case for not just the continued existence of the form itself, but the necessity of the concentration camp memorial experience.” – INDIEWIRE

“KZ, perhaps the first postmodern Holocaust movie … explores the subject in a different way. … Bloomstein … was making a TV documentary called “Liberation” when he noticed the beer drinking and singing taking place within yards of the former concentration camp. He was ‘haunted by the disjunction, the reality of people enjoying themselves, and then the reality over there’ at the camp, and decided to make a film that would show ‘the interface of memory and history and the present’.” - JEWISH JOURNAL

Excerpt from an interview with Jamie Bennett, now Governor of HMP Grendon Underwood, for an article in Crime, Media, Culture

JB: What was your purpose in making this film? Organizations like the Howard League have a campaign to abolish child imprisonment and to improve conditions. You have also mentioned measures such as ASBOs, and there has often been a public panic about what is perceived as ‘yobs’. What is your purpose - is it to see the abolition of child imprisonment, or is it to reform what is currently done, or is it to alter public perceptions?

RB: I think to alter public perceptions. This was not me saying we should abolish such places. Nor was it me saying reform them. In this film there was not time to consider these very important issues that you have raised and I don’t think this film was particularly the right vehicle for it, or indeed I am not even sure documentaries are the right vehicle, because these are deeply complicated issues. What I was trying to do was to humanize the subject, not untypically in relation to my other work, because I think these kids are demonized, they are made sub-human. They are often regarded as evil. There is no doubt about it, they are deeply troubled and problem kids, but it seems to me that there is a process of dehumanization which continues throughout the media, certainly the tabloid media. I felt that this film could do something not attempted before; it could present a living human being whose age is between 14 and 18, has committed numbers of crimes and offences, and who has agreed to answer questions from me. The questions I asked I think are the questions any sensible, reasonably intelligent person would ask and in doing so, deepens, even just a little, a notch, our understanding of why these kids are as they are.

JB: With Lifer: Living with Murder, you started to develop an almost exclusive use of interviews. Some of your other films, as well as interviewing offenders, have tried to explain the system. In this film you specifically focus on the people and don’t make an attempt to explain the process or the policies. Was that a deliberate choice on your part?

RB: Yes. There is a price to pay for an almost total concentration on the young people. The price I paid was that there was no time for greater context, such as some of the issues you mentioned of youth justice and indeed the view that no children should be in prison at all under 18. In my view, some are very disturbed children, and they have to be in secure accommodation, if only because the public and the children themselves have to be protected. However, undoubtedly there are too many of them inside and there are huge problems in dealing with these kids. Listening to them a lot of these questions emerge, but I didn’t want to make a didactic film. I wanted to focus on the children themselves.

JB: Jean Rouch, an early Cinema Verité practitioner described how that approach was most effective when dealing with marginalized figures. He described the camera as a window in and a window out: a window in for society to hear these people, and a window out by providing an opportunity for these people to be heard. Your films appear to be deliberately giving a voice to people who aren’t heard and don’t have an opportunity to be heard.