REXENTERTAINMENT

“The phrase that I have come to believe best sums up what the documentary film can most hope for, is to ‘undermine the simplicities’. The challenge is to present a much needed sense of flawed humanity not stereotypes.”

Rex Bloomstein

Rex Bloomstein has made over 150 single films, television documentaries and series and, in January 2012, presented his first radio documentary, Dying Inside for Radio 4. He is currently developing a number of further projects.

For full details about his work, follow the links below.

The 50th anniversary of the Universal Declaration came along in 1998, and the BBC were planning a human rights season of programs, so we we interrupted our usual run of Human Rights, Human Wrongs, to create a special series of programs. The 24-hour news culture was beginning to emerge then; the potential for us to know so much about what is happening in the world increasing all the time. Yet the need to alert people to human rights abuses remains just as important. If we care to listen, we could do so much more. I particularly wanted to attack what I saw as this disjunction - to continue to make viewers aware, to make them angry, and to make them want to do something. I had been much impressed by Amnesty’s Urgent Action campaigns, on behalf of individuals or groups in need of emergency help. So we decided to go back to the five minute slot and concentrate on individual stories from around the world that demanded - Urgent Action.

In the end we made ten films, with Caroline Moorehead again co-producing, featuring people from a number of countries, with explanatory commentary from myself and without presenters. We created a web site and automated answering system giving names and numbers of Ambassadors and Embassies. I should say that I personally didn’t film in many of the countries we featured but instead commissioned BBC correspondents, or stringers, or human rights groups, or in one case a charity to get the material we needed. We then edited in London. A total of 17,000 rang the BBC - some 25,000 contacted the BBC’s web site and several Ambassadors got very unhappy indeed. The programme that got the most response was Women under the Taliban. Some 7,000 people rang and 3,000 got through.

By the time we finished the series, and several months later, we heard that a prisoner we featured from China had been released. I believe a number of results were achieved over these 11 years; we alerted a TV audience to the importance of human rights, perhaps made activists of some of them and, who knows, all those letters and messages from people all over the UK might have had a direct impact on getting a prisoner freed. I cannot prove this, but at the very least, this particular group of people were not forgotten. It was also my hope that our series, Prisoners of Conscience and Human Rights, Human Wrongs might have inspired other programme makers and networks in different countries to do the same – using what we tried to do as a template. Because I believe with the right approach, you can make people care.

Roots of Evil Part One: Ordinary People

The struggle between good and evil takes place all over the world, in every city, in every town, and in every community. This struggle is at the very core of the human condition. Is evil a malignant force outside of human control, or is it an integral part of every human being? This first film in the series examines the notion that most evil acts are committed not by monsters, but by ordinary people.

We ask how the great religions such as Judaism, Christianity and Islam come to terms with the existence of evil? What sort of man is Donald Harvey, a serial killer who confessed to the murder of 87 people? Is Detective Inspector Albert Kirby right when he asserts that the boys who killed the toddler, James Bulger, were born evil? What prompted neighbours to slaughter neighbours as happened in Bosnia and Rwanda? Why did the G.I. Ron Ridenhour expose the actions of American soldiers in the My Lai Massacre during the Vietnam War?

These and other questions are also illuminated by experts - Professors Robert Lifton, Ervin Staub and Fred Alford. If, as it is suggested, the vast horrors of this century have been committed by ordinary people, then we must all address what it is to be ordinary.

Roots Of Evil Part Two: Torturers

‘Torture is something that States deny. Torture is something that happens in secret. It’s a crime. It’s forgotten. But it’s a crime, a crime committed by law-enforcement officials, and people who are supposed to be upholding the law’. Thus Nigel Rodley, who reports on torture to the United Nations, shows us that this ancient horror continues to be practised in the modern World - in Torturers, Part Two of The Roots of Evil.

The film begins by revealing how ordinary young students can commit evil in the unique Stanford Prison Experiment, and how young soldiers can be conditioned to the practise of torture in Brazil. The example of Argentina shows the extent to which a country can be corrupted by the widespread use of torture as happened during the 1970s Dirty War. Also revealed is how a democratic country such as Israel condones the practise of torture in the name of anti-terrorism. But it is the tragic story told by Mikael Suphi of his experience as a torturer for the Turkish army, that encapsulates how an innocent young man can be turned into a torture machine. As he says “They make up that monster inside of a human being, they take out all the good and they put the bad inside”.

Roots Of Evil Part Three: Tyrants

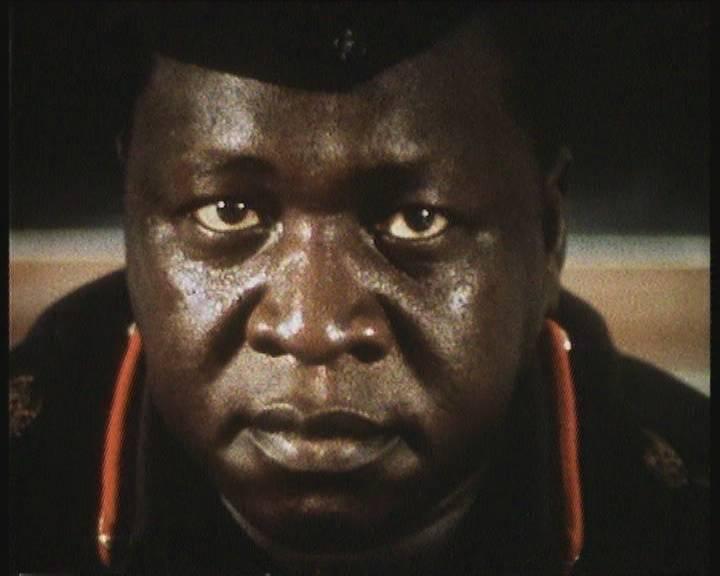

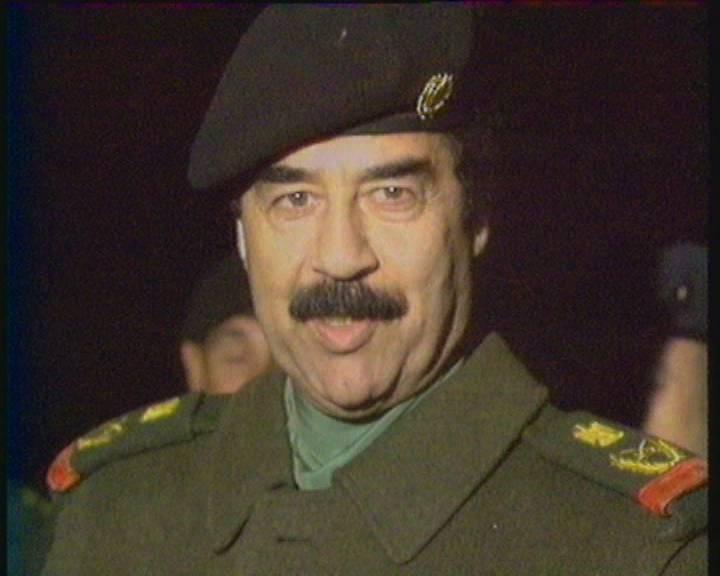

Part Three of The Roots of Evil looked in depth at tyrants. Idi Amin, an old fashioned tyrant responsible for the death of tens of thousands during his period of rule in Uganda. Saddam Hussein, an ultra nationalist tyrant whose reign of terror in Iraq has included gassing, murder, and the destruction of whole communities. Pol Pot, an ideological tyrant, who committed genocide in his attempt to change Cambodia in the most extreme revolution the world has ever seen. Tyrants are the incarnation of evil. This film examines the lives of these men who exercised absolute power and have been corrupted absolutely.

It was in the Washington Holocaust Museum’s bookshop that I saw a copy of ‘The Roots of Evil’ by the American psychologist, Ervin Staub. Inspired by its sweep and scope, it became clear to me that I must try to tackle this subject on film. John Willis, Director of Programmes at Channel 4, eventually commissioned three one-hours. After much discussion with Ervin Staub, who became a consultant and appeared in the films, a trilogy emerged:

Part 1 - Ordinary People - reveals how most ‘evil’ acts are committed by ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances.

Part 2 - Torturers - includes shocking testimony from victims and perpetrators and looks at how torture is routinely practiced in a third of the world’s countries.

Part 3 - Tyrants - examines three 20th Century tyrants in depth - Idi Amin, Saddam Hussein and Pol Pot - who had devastated the lives of millions of people.

“Roots Of Evil was a fascinating documentary made with skill and belief and, crucially for a programme with this subject matter, maturity.” - THE DAILY EXPRESS

“... it was vastly illuminating to follow Roots Of Evil’s exploration of ordinariness.” - THE GUARDIAN

“Is evil something that exists outside ourselves or is it an intrinsic part of being human? Can a propensity for evil be inherited or is it a product of conditioning? And how is it that ordinary people can commit extraordinary acts of violence against each other? These are some of the questions that this lucid and powerful documentary by Rex Bloomstein, the first of three exploring the roots of evil, seeks to ask if not answer.” - THE TIMES

“Why Men Become Monsters

What drives people to commit wicked acts? Are torturers born or made? Is it possible to stop a country collapsing into tyranny by speaking out early? These are the profound questions raised by the human rights documentary-maker Rex Bloomstein in the austere but compelling series, Roots of Evil.

‘I’m trying to prompt the audience to think more deeply about the issue. There are explanations,’ Mr Bloomstein says. “The ordinary viewer needs to look at himself and understand how fragile civilised behaviour is. Even in a totalitarian regime, there are moral choices. People choose.’

What emerges through the programmes is not sermon, nor conventional documentary. Mr Bloomstein pursues his theme around the globe, through interviews with torturers and academic experts and psychologists. These are threaded with minimal commentary, and no music or special effects. It is television without frills. The urgency makes it compelling.

Mr Bloomstein, 55, is well qualified to tackle this huge issue. He founded the regular BBC2 series Prisoners of Conscience (based on Caroline Moorhead’s regular newspaper columns), which campaigned for individual sufferers. Much of Roots of Evil can be traced directly to the contacts Mr Bloomstein has acquired as a documentary-maker and humanitarian. He arranged and conducted interviews with ex-torturers because of this knowledge, from victims, of where the guilty men could be found.

Trained at the BBC - he made his first film in 1970 - he is most often associated with Strangeways, the award-winning series in 1980 about life inside the prison. It is credited with stimulating the creation of the Penal Reform Trust. The programmes also helped to open up prisons to the cameras. He has made 17 films about penal life, including Prisoners’ Wives, The Sentence, Release and Lifers.

And he is a co-founder and trustees’ chairman of the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture, the British charity that tries to rehabilitate refugees. Mr Bloomstein belongs to the old school of programme-makers who believe in public service broadcasting.

‘I believe documentaries can activate people to do things. There is no point in being worthy but dull. I have spoken, more than most, to people who have committed terrible crimes. One is struck forcibly by their ordinariness. There is a huge gap in our understanding of how apparently ordinary people do these things. Because they are in a minority… it can be that at times of enormous dislocation, social upheaval, unscrupulous men and women can test depths of human potential for destruction and cruelty. I wanted to pose the question: how can a man become a torturer, how can a man kill his neighbour? Is evil within or outside?’

The series roams between Cambodia, Rwanda, Argentina, North America, Israel, Turkey and Britain, eclectically gathering information, which is spliced with historical footage about three particular tyrants, Idi Amin, Pol Pot and Saddam Hussain.

And they fit well with the current mood: The Nazis, A Warning From History, on BBC2 has a very similar message about the choices individual people made in colluding with Hitler’s terror. Next Sunday’s program examines how torturers are shaped and motivated. Mr Bloomstein explains how they are both brutalised and given an ideology, so that they treat their victims as both dehumanised creatures and threats to society.

One of Mr Bloomstein’s coups is an interview with the Argentine torturer Adolfo Scilingo: he explains how he stripped and pushed drugged students, ‘the Disappeared’, our of aeroplanes over the Atlantic. One ex-torturer, unnamed, filmed in shadow by Mr Bloomstein, calmly explained that the aim was to get the information by breaking the victim in three hours.

‘Minimum physical damage, maximum degree of pain’. He talks beside an electric grill ‘bed’, which combines with the picana, a type of electric prod, to form the theatre for torture. ‘Prisoners died on this bed,’ he says.

He believes that brutalising men - his film shows the process used in Brazil of forcing cadets to crawl through sewage and blood and beg for food - is only part of the story. They have to be given a motive for viewing their victims as sub-human. ‘Idealism can be the most devastating impulse. It can cover a multitude of sins and can be an excuse for unmitigated horror’. In many countries the authorities recruit torturers from the military police, and sift out those who are conditionable. ‘They don’t like people who are too ruthless. They like controlled people’.

In another frank interview, the ex-Turkish torturer Mickael Sufhi, explains how he was selected from the ranks of new soldiers, and sent to an interrogation centre in Ankara. For two days, the recruits were themselves tortured into a state of compliant fear.

Sufhi describes how they were taught the falala, beatings on the feet, until ‘pieces of meat’ came away, and how he forced one victim to eat newspaper. But he cracked after a week, when he was told to torture an eight-year-old boy. ‘It was too fast. That child probably saved my life’.

As Mr Bloomstein insists and his programmes teach: there are answers. Evil is fabricated within people, the potential runs through the heart of every person. These are not perfect programmes. But they make you think.” - THE TIMES, Maggie Brown

It had become clear that by the mid nineteen nighties the numbers of prisoners of conscience were declining world wide. It was time to change our BBC 2 Prisoners of Conscience series which had run for 5 years, so the decision was made to expand the former five-minute format to give more context and more time to chosen themes. A new 10-minute slot emerged, again with a presenter and again retaining a personal story, but this time taking as our focus a different subject or issue such as Genocide, Censorship, Slave Labour, Violence Against women and so on. We reduced the programmes to five, spread over the second week of December. Again the public were asked to phone in and ask for an information pack. The new series was co-produced by Caroline Moorhead and myself and called Human Rights, Human Wrongs. Presenters included Salman Rushdie, Arthur Miller, Meryl Streep, Isabel Allende, Richard Dawkins, Helen Suzman and Anthony Hopkins. The series ran for 5 years.

“From Rex Bloomstein comes a new series of short films, introduced today (International Human Rights Day) by John Simpson, who looks back at 1995 and finds little to celebrate. From tomorrow until Friday Isabel Allende, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Catherine Deneuve, Dr Richard Dawkins and Billie Whitelaw focus on various aspects of human maltreatment.” - THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

In 1992, Channel 4 created a season on the homeless called ‘Gimme Shelter’. I had been aware of Arlington House, a Victorian hostel for homeless men in Camden Town, North London, for a number of years, and often thought about its potential for a documentary. The Channel commissioned it and much of what I felt is quoted in the reviews below.

Let me say that it’s not hard to imagine the problems that can beset any of us, for whatever reason, that lead to homelessness: family break-up, unemployment, mental health problems, addiction and so on. But when it does happen, it is harder to imagine how catastrophic and life-changing it can be. So there it is, this great Victorian pile - 400 single men; 400 hundred stories.

What Do You Expect, Paradise? emerged from these.

“If Paradise Is Half As Nice

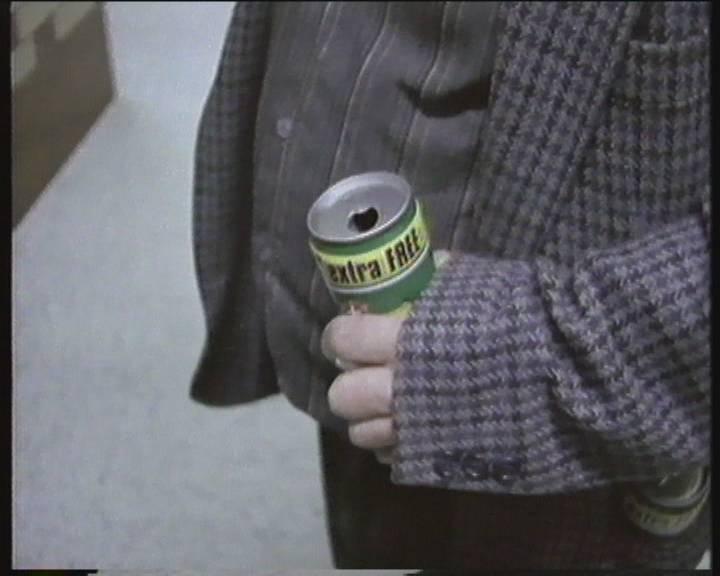

Lager can in hand, Gerry sings ‘Roamin in the Gloamin’ while beside him Peter paints a mural on a bare corridor-wall. This is a typical scene from the bizarre life of Arlington House in Camden Town, north London, Europe’s largest hostel for homeless men, as captured in What Do You Expect, Paradise? (9pm C4), Rex Bloomstein’s engaging contribution to the ‘Gimme Shelter’ season. Inevitable, some residents appear to have been released from other institutions for ‘care in the community’. Theft is so rife that the figurines gathered around a Nativity crib have to be locked in a glass case to prevent them from being ‘kidnapped’. But overall the film serves to contradict the stereotype of the homeless man as a drunken illiterate. Peter the painter quotes Rembrandt on the art of self-portraiture: ‘I sense all the misery in my face’. Seamus, an articulate former chemist and property dealer, says he can cope with Arlington House because it is not dissimilar to the public school he attended. And an Ulsterman called Joe eloquently explains the effect the murder of 15 of his friends had on him: ‘the true homelessness is within yourself; I’ve never felt at home anywhere in the last 20 years’. Touches the heart as well as the mind.” - THE INDEPENDENT, James Rampton

“Home and dry

Dossers hanging out around the Tube are part of the furniture in Camden Town. Most of us don’t give them a second glance, but tonight’s main item in Channel 4’s ‘Gimme Shelter’ season, ‘What Do You Expect - Paradise?’, will make you pause next time you pass that way. It’s a vivid portrayal of life in Arlington House, the Victorian gothic pile around the corner that provides a home for 400 single men. And, unlike the majority of documentaries in this almost overwhelmingly depressing season, it provides a glimmer of hope.

‘There are any amount of stereotypes of down-and-outs, dossers and drunks that are pretty negative to say the least,’ says the film’s producer-director, Rex Bloomstein. ‘I wanted to undermine those images by showing the men’s humour and warmth, as well as the sadness.’

Best known for his 1980 series on the Manchester prison ‘Strangeways’, Bloomstein has a fine track-record of filming in institutions. In this case, he didn’t have to look far. ‘I live in north London, and it always interested me to learn what went on in that huge Victorian building. In a very basic way, I wanted to know how the place worked and how the men lived’.

There’s no question that his film does that; in an apparently artless way, it enables the tenants (and staff) of Arlington House to tell their stories, vent their feelings, and reveal their humanity. The film builds into a compendium of mini-biographies that underline the importance of security and shelter as the starting point for recovery from personal tragedy or illness. Above all, there’s a sense of reconnection, both among the tenants and of Arlington House itself. After being taken over by Camden council in partnership with a housing trust, Arlington House has been transformed from a Victorian hostel crammed with 1,000 tenants to a halfway house for 400 men.

‘For the vast majority of men who live there, I suspect it’s a very good place to be,’ says Bloomstein. ‘For some it’s a staging post on the road to recovery, for others with secure tenancies it’s a real home. It brings dignity to the lives of a lot of people who’ve never known any. It took three years from his first approach before Bloomstein was allowed inside with his camera, sanctioned by a ballot of the tenants. Research and filming occupied two months off and on, either side of last Christmas. There’s no sense of intrusion as the tenants reveal themselves in often eloquent cameos. The result is absorbing viewing that shows even the most rootless can put their lives in some sort of order when they have a roof over their heads. No moment is more telling than the answer to Bloomstein’s off-camera question ‘What’s wrong with him?’, asked of a man remaining stubbornly morose as others enjoy an evening of Irish music. ‘Same as all of us,’ comes the response. ‘Just getting over his problems’.” - , Geoff Ellis

“Deserts for the deserving

You braced yourself for What Do You Expect - Paradise? (C4), Rex Bloomstein’s portrait of Arlington House, which accommodates around 400 homeless men in Camden. Anyone who has walked the pavements that surround the great Victorian pile knows that the incidence of incoherent abuse, rambling pledges of affection and slurred chorales are as high as anywhere in London, so it seemed likely that the interior would be something out of Dickens, a sordid warren of decrepit corridors, squalid bedding and unexplained puddles.

What was actually revealed inside was astonishing - a clean, well-maintained hostel in which the dispossessed could find privacy, clean linen, some security and basic human sympathy. The punitive institutional architecture of Victorian benevolence had been partially tamed and the conditions in general would put many hospitals to shame. You never found out whether this is the result of munificent funding from Camden Council or simply exceptional management, but whoever is running the place should be asked to apply their talents a little more widely - they could sort out London’s problems first and when that’s done turn their attention to the country as a whole

When it was built, Arlington House was intended to house 1,000 working men - not destitutes, but the deserving poor. Now that the rabbit-hutch cubicles have been expanded it will hold just under 400 guests, each of whom will have been interviewed before they are given a room. On the evidence of some conversations in the film this cannot be an easy procedure. How do you interview a man who replies either without the use of consonants or with a medley of Harry Lauder songs? With considerable reserves of patience, I guess, a quality which Bloomstein’s touching film also had in large measure.

From the opening scene, in which a sprucely dressed man sang a song to prove that ‘everybody here isn’t a vagrant’, Bloomstein was at pains to listen to the men’s account of themselves, narratives shot through with pained candour and self-justification. One man, who had fled from the violence of Northern Ireland said of alcohol that it had given him ‘a glimpse of being without fear’.

A former public schoolboy, features now hidden behind a paste-brush beard, pulled tightly on a tiny roll-up as he explained how his father’s legacy had run out. He hated alcohol, he declared, though ‘I once tried ether - I looked it up in a medical book. It’s non-toxic and it gets rid of phlegm on the lungs’. He delivered this with a dry chuckle, a familiar sound in these bitter recollections, sanding the edge off remarks which would otherwise leave splinters in the mind.

‘It breaks my heart to look at the bastards’, said another guest. ‘I think I’d sooner be in hell’. Then he chuckled too, as though laughing at his own caricature of misery. Another man shook as he described how he had lost his lover through drink, his eyes trembling with tears like an overfilled glass. That you emerged from this hour feeling hopeful says a considerable amount for the businesslike love of those who run Arlington House and for the humane optimism of Bloomstein’s regard.” - , Thomas Sutcliffe

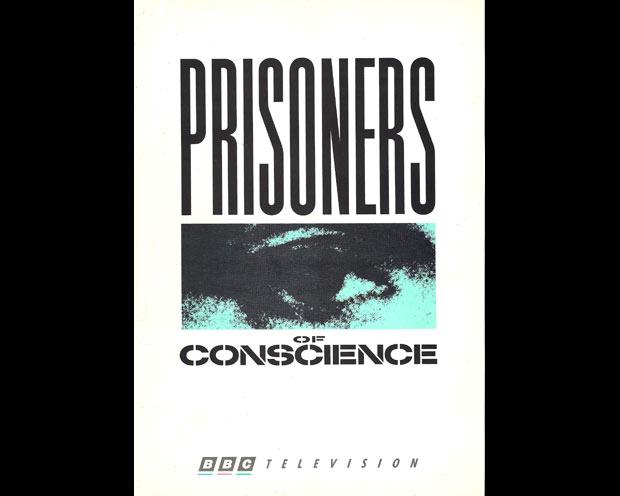

An annual series of 10, five-minute appeals on BBC 2, timed to coincide with 10th December, Human Rights Day, featured prisoners of conscience from around the world. Eminent presenters, from the arts, politics, science and sport, told the stories of these innocent men, women and children imprisoned in different countries and urged the audience to protest at their imprisonment and campaign for their release.

Excerpt from my lecture Human Rights, Does Anyone Care?

In the late eighties I noted a column in the Times Newspaper called ‘Prisoners of Conscience’. It was written by Caroline Moorehead. It struck me that I could do the same as Caroline was doing so compellingly in her column, namely highlighting an individual case of an innocent person unjustifiably imprisoned, but this time do it for television. Of course the concept of ‘Prisoners of Conscience’ had been developed by Amnesty International.

Caroline joined me as writer and we first went to Channel 4 who turned it down. We then persuaded the BBC, with the help of Executive Producer, Jenny Barraclough, and the Head of the Department, Mark Thompson, to produce 10, five-minute programs over two weeks - Monday to Friday - around Human Rights Day on the 10th December. Anne Morrison eventually took over as Executive Producer for the BBC.

Among the things we wanted to do was obviously to get the audience to watch such a series, and then to get them involved in trying to secure the release of an innocent person. To do what human rights organisations all over the world were doing, as well as bringing attention to the often appalling conditions and treatment that prisoners endured. A further point was that I decided we should get high profile and distinguished people to present the programmes to help make it as compelling as we could.

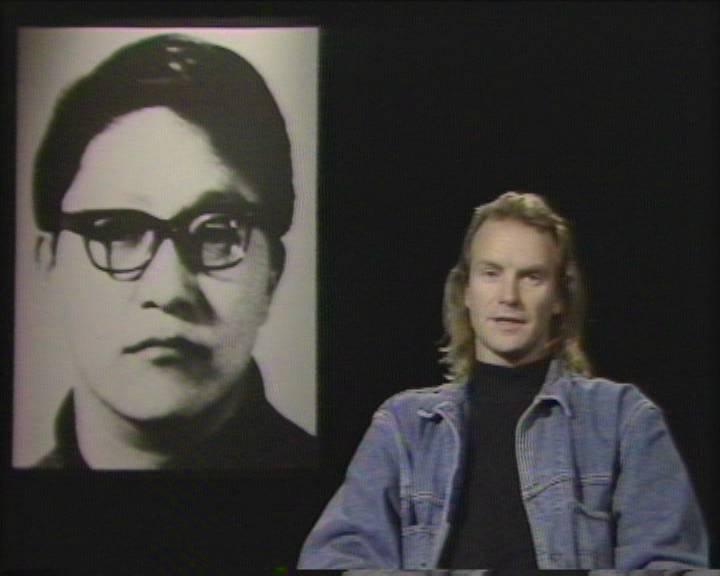

The first programme we ever did in our Prisoner of Conscience series was presented by Sting.

What were our main difficulties? Obtaining as much information about the case – finding as many visuals as we could including photographs, film footage to illustrate the case.

Who were our sources? All the major NGOs such Amnesty and Human Rights Watch, as well as smaller organsations and individual journalists and observers.

What effect did we have? An average of some 10,000 people either wrote or rang the BBC each year for an information pack that gave details of how and where to write on behalf of the prisoner. Of the 64 prisoners of conscience featured over those five years, at the last count over 40 are now free.

I became aware that we were soon approaching the 20th anniversary of the death of one of the 20th Century’s great figures - the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King on 4th April 1968. The brutal martyrdom of the civil rights leader whose courageous stand on the principles of non-violence had helped tear down the structures of racial injustice. Ian Martin, then head of Thames Documentary Department agreed we should make Martin Luther King: The Legacy. We would assess in the film the extent to which his dream of an integrated society has been realised for America’s blacks. It reveals the character of one of the greatest orators of our time and the FBI’s campaign to destroy him, retraces the historic march from Selma to Montgomery, and revisits the black ghettos of Chicago, at the time the most segregated city in America.

“20 years after King’s dream

The dream of the Civil Rights movement in America still waits realisation some 20 years after the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King. At the time of King’s campaign of civil disobedience, which helped end America’s version of Apartheid, TV news reporting began to use colour, which gives much of the historical footage used in Martin Luther King: The Legacy the look as if it happened only yesterday. For all the changes in the conditions among the shacks of the South and the high-rise slums of the North, it might have done. Rex Bloomstein’s harrowing documentary highlights the inequalities which still exist among America’s poor; the meaning of ‘the wrong side of the tracks’ in Chicago 88 is starkly illustrated. Despite the initial successes of King’s campaign, achieved against a backdrop of brutal bigotry and establishment opposition, members of the movement like Andrew Young, now Mayor of Atlanta, and Rev Hosea Williams cite examples in the Eighties of stonings, burnings and Klan lynchings. Pictures of the march in Forsythe County last year bear an uncanny resemblance to the bloody scenes outside Selma, Alabama, 22 years before. Notably, Jesse Jackson, one of the men at King’s side when he was shot is not interviewed in the film. If King’s dream is to be realised, then much will depend on the success of Jackson’s Presidential campaign.” - THE INDEPENDENT, Steven Downes

“Rex Bloomstein’s film Martin Luther King: The Legacy (ITV) was a long documentary which could well have been longer. As its title suggests it took on both the memory of the man and what his work has achieved. This made the film both very moving and profoundly depressing. On the plus side, there were the familiar images of Dr King and his companions marching with great courage and dignity through jeering white rabbles and vicious white policemen. And there were retrospective interviews with some of the old campaigners, including Andrew Young.

The fairly recent history of America is, in this respect, quite amazing, and was here revealed in all sorts of subtle ways as well as through the black and white footage. For example, one campaigner reminisced about a decision to move the marchers on to Montgomery: ‘There was a judge there that had a reputation for justice’.

On the depressing side, and almost worse than the vicious stupidity of the white crowds of the 1960s, were the contemporary scenes of desolation in segregated Chicago. Not much, it seems, has been achieved. The dream is still a dream. The black middle classes and intelligentsia have moved out of the inner cities, leaving the rest in decaying squalor. Even black professionals - one banker described himself as a buppie or black yuppie - have made slow progress.

Perhaps the film took on too much history and social analysis - certainly it was at times indigestible. I also found it distracting to see busy contemporary shots say of children in a school bus, as background to a piece of King’s oratory. Words and pictures were fighting with each other.” - , Minette Marin

“… It was a militant belief in the ideals of the Civil Rights Movement, rather than sheer optimism, that inspired Andrew Young’s verdict at the start of Martin Luther King - The Legacy (ITV): ‘We started out to redeem the soul of America, to rid America of the evils of racism, poverty and war… I think we came pretty close’. An hour and a half later, by the end of a superbly-orchestrated tribute to the man and his work, it needed a great deal of faith to believe in impending redemption. The film left no doubt that in some respects the soul of America has hardly budged in 20 years.” -

“Martin Luther King: The Legacy

Give a TV producer an anniversary and s/he will give you a 26 part series complete with accompanying book, T-shirt and hot water bottle-cover quicker than you can say ‘Alan Whicker’, as all you bicentennial-bashed viewers no doubt know to your cost. So it’s surprising that Thames is marking the assassination of Martin Luther King with a one-off programme rather than something a bit more substantial. It’s difficult to cram the history of the civil rights movement, and a profile of a modern day Gandhi into 90 minutes and still have time to examine his legacy. But despite the cramped slot, the programme-makers produced an excellent piece. We trace the preacher from Alabama from his early days in the South to his death in 1968. King’s policy of nonviolent confrontation meant that he (his followers) went forward day after day to have the blow fall on the same bruised spot that it had landed on the day before, until King was killed. The fact that this was the logical conclusion of his activism was not lost on the man. ‘Every morning when I wash my face, I look death in the mirror’ he told one of his friends. While the historical aspects are engaging enough (although there is no interview with Coretta King), the programme gets much more interesting when it looks at how much things have changed as a result of the movement. The answer is not a lot. Blacks may now be able to vote without fear of being beaten up but political power, without economic muscle, is just a philosophical privilege which won’t put food in your belly. In certain cities, infant mortality among black children is higher than in some third world countries and joblessness and bad housing is just as bad as ever it was. Even worse the Ku Klux Klan can still burn down a black boy for no other reason than to show its strength and black people who move into a white neighbourhood may not find their house standing the next day.” - , Alkarim Jwam

“There were moments in Martin Luther King: The Legacy (ITV) which were almost unbearably moving, including grainy film of some of the early civil rights marches, and the scene on the Memphis motel balcony where the apostle of Ghandian non-violence was gunned down 20 years ago next month.

I remember listening to Dr King in Chicago a year earlier and wondering why his non-violence provoked such violence and fear. The answer came to me last night: it was, I think, his constant rhetorical repetition of the word ‘Now!’ in relation to his demands. But would anything ever have changed if he had muted his oratory?” -

“King who dreamed of a promised land

Martin Luther King: The Legacy on ITV was both inspiring and depressing.

This excellent documentary looked at the life of the black preacher whose personal courage and inspired rhetoric did much for the negro civil rights movement in the United States.

Anyone with a vestige of human feeling could not fail to have been moved by the sound of his voice and newsreel shots of the protest marches he instigated.

But it was sad to face the realisation that 20 years after his assassination, racial bigotry persists.

You can pass laws giving blacks political freedom, but laws do not erase prejudice, nor do they ensure equality of economic opportunity.

It was pointed out that although President Lincoln gave slaves their freedom, he gave them no land, which was like releasing an innocent prisoner from jail without giving him the bus fare to anywhere.

As Martin Luther King said, it is all very well to tell a man to lift himself up by his bootstraps, ‘but it’s a cruel jest to a man without boots’.

The promised land he envisaged is still just a dream, but his successors are struggling to make it a reality.” -

BBC programme notes for publicity:

Le Bourget, the airfield made famous by Charles Lindbergh’s landing after the first transatlantic flight, would have been long forgotten were it not the modern setting for the most formidable collection of arms, ammunition and aircraft to be placed on collective display anywhere in the world. The biannual Paris Air Show is the market place for the world’s premier aeronautic manufacturers. A seemingly innocent display of civil aviation gives way to a remarkable array of planes, missiles, electronics, avionics and scientific wizardry designed by some of the planet’s smartest people to facilitate the effective destruction of mankind, Please God, Don’t Let Peace Break Out is a filmed portrait of this extraordinary event by Rex Bloomstein, whose documentaries include Strangeways, Auschwitz and the Allies, Lifers, and most recently Attack on the Liberty.

The film is a mosaic of images, scenes and vignettes drawn from the 10 days of the show and is without commentary. We see the arrival of President Mitterand; the competition between the new European fighter, the American F16, and the French Rafale; the Russians exhibiting only civilian aircraft while being second only to the Americans as the largest exporter of arms in the world; Rockwell Corporation displaying the gigantic Bl bomber and extolling its destructive fire power at a press conference. The British selling to the Indonesians; the Israelis selling their planes to the Nigerians; the French, their aircraft to the Egyptians; the Italians, the Brazilians and the Swiss offering their range of missiles and anti-aircraft guns; the magnificent receptions like the Canadian Embassy’s dinner at the ‘Conciergerie’ in Paris, and Agusta, Italy’s premiere helicopter company hosting a fashion show at the Grand Hotel.

Videos thunder their military products as the public wander in their thousands around the displays. Children fondle missiles and gaze wonderingly at these images of war. The more awesome the destructive power of the weapons on show, the glossier the packaging and the slicker the marketing techniques used to sell them. The ironies are endless. The opulence incredible. The technologies dazzling. It is the message of the show however, that is horrendous: the universal homage to the god of destruction. As the film’s last caption records:

“In 1986, the International Year of Peace, global military expenditure reached a record $900 billion - $1.7 million a minute…”

The Paris Air Show was suggested to me by the Israeli journalist and writer, Hirsh Goodman. He had attended the bi-annual event at Le Bourget and was amazed by the ironies, contradictions and lavishness of the arms trade on show. It led to my first independent production, an impressionistic portrait of the Paris Air Show – the most formidable array of arms, ammunition and aircraft assembled as anywhere in the world. Ever more sophisticated methods of destruction are sold by high-powered salesmen against a backdrop of beautiful women, lavish hospitality and extraordinary technical wizardry.

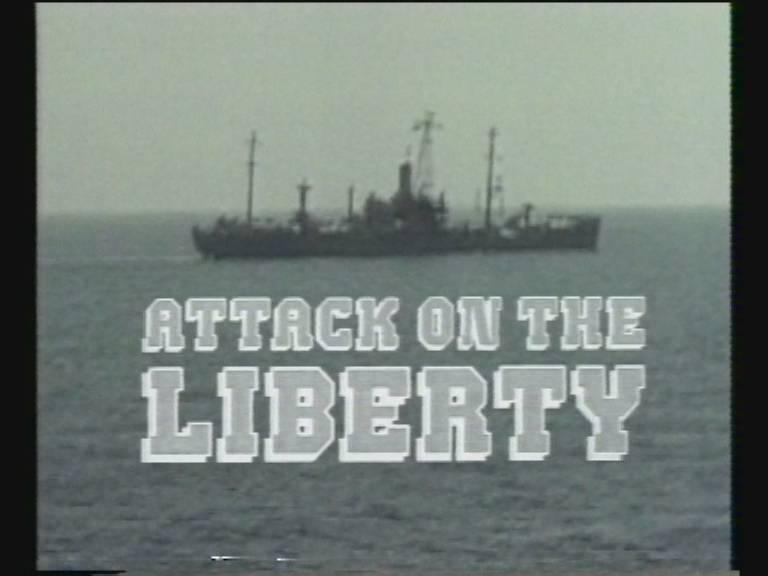

I became fascinated by a story that seemed as first sight an appalling and deliberate attack on a spy ship by the Israeli Navy and Airforce during the Six Day War. The facts were these: on 8th June 1967, the United States electronics intelligence ship, the USS Liberty, was steaming 14 miles offshore from the Egyptian coast. It was the fourth day of the Six Day War. Suddenly, two mirage jet fighters appeared over the Sinai Peninsula and, with devastating accuracy, proceeded to attack the virtually unprotected American vessel. Two bombers followed and, as the air attack ended, the Israeli Navy fired torpedoes.

Sixty-five minutes of bloodshed left 34 sailors dead and nearly 200 maimed and wounded.Was this a tragic accident, or a deliberate act of destruction? The official US/Israeli version has always been that Israeli forces mistook the USS Liberty for an Egyptian warship. But this is hotly contested by survivors who claim the attack was premeditated and deliberate. So what was the truth - the fog of war or a scandalous cover-up?

In Attack on the Liberty I examined these claims, fully prepared to believe the survivors’ stories as they told them to me. Frankly, I could not believe that the Israelis did not know the identity of the ship, with its American flag and clear large letters on its hull. The film digs deep into the rival claims, but in the end reveals an extraordinary story of appalling communication failures and the stress and panic of war. The verdict of what actually happened is left to the viewer.

I

“Victims of the truth

Rex Bloomstein’s investigation of a 20-year-old mystery, Attack on the Liberty (Thames) failed to convince me of any particular thesis.

In the end it was still impossible to identify a villain with any certainty or to feel any of the agreeable heat of righteous indignation. But this failure (from the investigative journalist’s point of view) was Bloomstein’s success.

The American spy ship USS Liberty was strafed, napalmed and torpedoed by America’s allies, the Israelis, on the fourth day of the Six Days War.

Men died in a pathetic state of shock and bewilderment and those who survived have not got over it. Bloomstein may not have produced a shock-horror scoop, but he told the story of their ordeal with vivd sympathy.

There are two possible explanations of the attack. One, the official version, is that the Israelis blundered.

Messages were misrouted. Calculations as to the ship’s position were mistaken. The reports of the pilots flying the jets were misinterpreted. By the time they had told their headquarters that they had seen CTR 5 (an American identifying code) on the side of the ship, the torpedoes had already been launched. And so on. It was all a ghastly mistake. The Israeli government apologised profusely and paid damages to the dead men’s families.

The unofficial version, advanced by Bloomstein, is quite different. The Liberty was eavesdropping on Israeli radio communications. The next day the Israelis were to launch their attack on the Golan Heights. They did not want the Americans to pick up any information about this. They especially did not want the Liberty, deliberately or inadvertently, leaking such information to the Arabs.

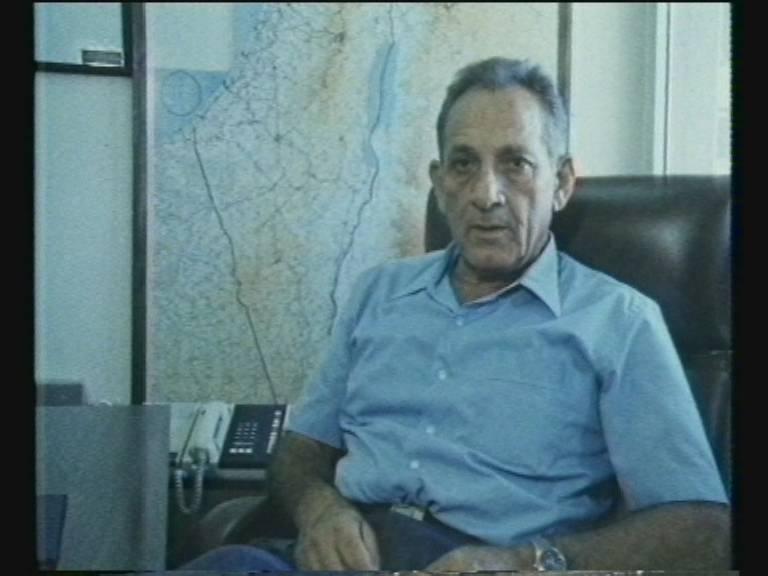

So an order came from very high up, probably from Moshe Dayan, to destroy it. After the war the US government accepted the ‘mistakes’ story for diplomatic reasons.

Bloomstein balanced his documentary scrupulously. In the first half men who had been sailors on the Liberty, and American high-ups including Dean Rusk spoke for the cover up theory. In the second half the Israeli top brass put their version. Appalling though it is that 34 men might have been killed by accident, and nearly 200 wounded, the way the Israelis told it, it sounded quite credible.

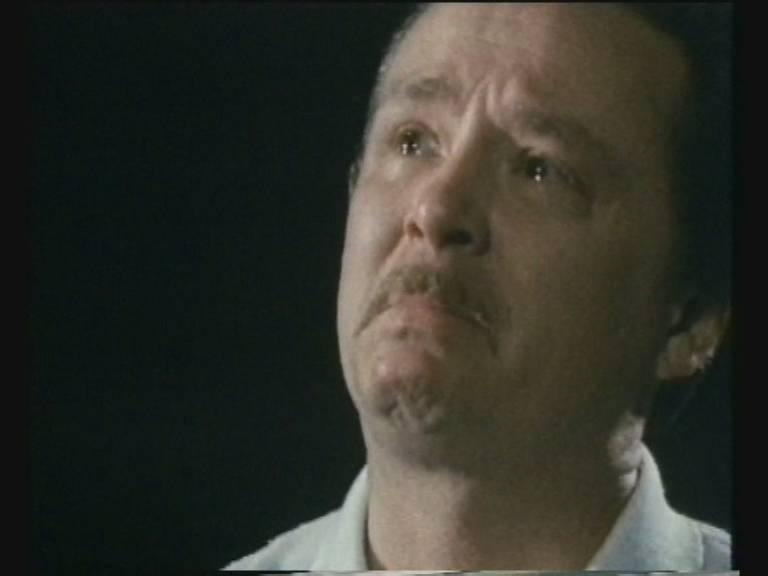

Interviewed in a darkened studio, the survivors described the horror of being strafed in confined space. A tearful one explained that he feels all the worse because he doesn’t know who to blame. American and Israeli governments have come and gone since 1967. ‘I can’t direct my anger there’.

What emerged with disturbing clarity from this elegant and powerful film was that, whichever story is true, he and his mates were cannon-fodder.” - , Lucy Hughes-Hallett Evening Standard

Torture is practised in over 70 countries. It is a global phenomenon, although banned under international law. From extreme physical brutality to the sophisticated use of drugs and electricity, it comes in a number of forms and many victims believe this terrible, traumatic experience will always remain with them and may even be passed indirectly to their children.

But are torturers psychopaths or can anyone be trained to torture another human being? What conditions are necessary for torture to flourish? Can victims be helped? These were among the questions I asked in this exploration of torture in 1984, in which perpetrators talked to me about administering terror and victims spoke about enduring these terrifying experiences.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was passed in 1948 yet every day we hear of civil liberties being violated in countries round the world, of justice taking second place to greed and manipulation, of fundamental rights being abused. The words ‘Human Rights’ roll glibly off the tongue of many a diplomat or politician. But what do they actually mean? Whose human rights? Do one man’s rights encroach or violate his neighbour’s? How do East and West interpret human rights?

I wanted to investigate this relatively modern concept and record the development and advance of human rights since the Second World War; how the international community tries to implement them through the various bodies that have been created – and what they actually mean for victims and perpetrators; to examine if the machinery of human rights can actually make a difference to people’s lives when so many vested interests stand in the way of a safer and more just world.

Human Rights is a two hour film, that attempts to examine and explore these questions placing the idea of rights in its historical as well as a contemporary context. The film looks at the developments in the United Nations in Geneva and New York as well as the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. Filming took place all over the world , from Hungary to the Philippines, from Russia to the Sudan.

Women in Afghanistan

Women in Afghanistan

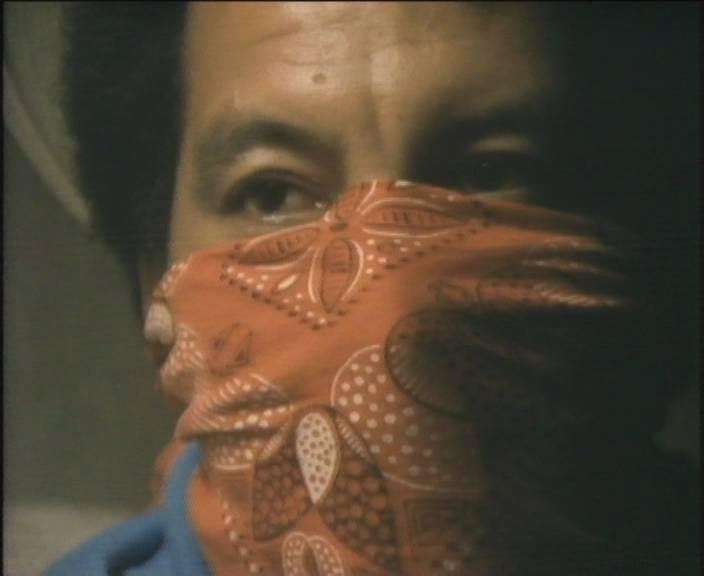

Torture

Torture

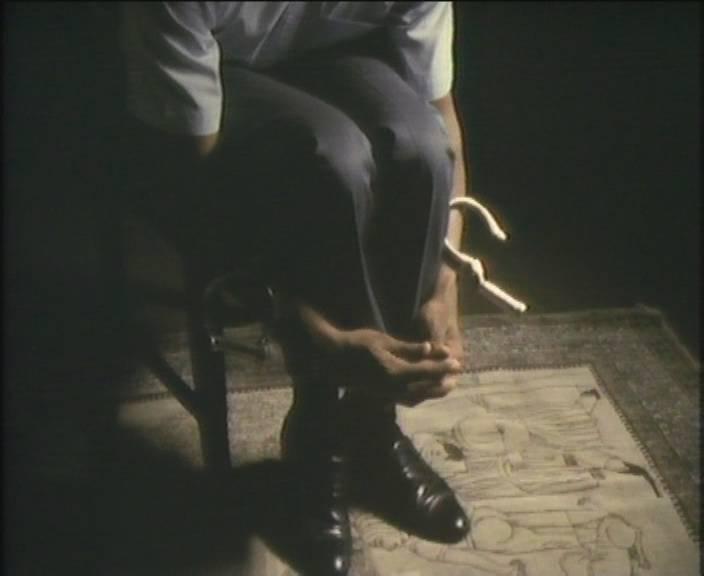

Torture and imprisonment

Torture and imprisonment

Programme 1 - Ordinary People: Depiction of Satan

Programme 1 - Ordinary People: Depiction of Satan

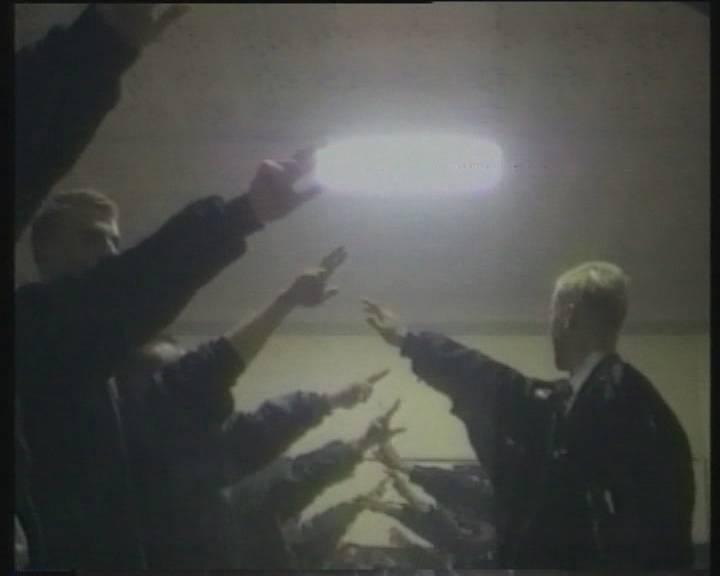

Programme 1 - Ordinary People: German neo-Nazis

Programme 1 - Ordinary People: German neo-Nazis

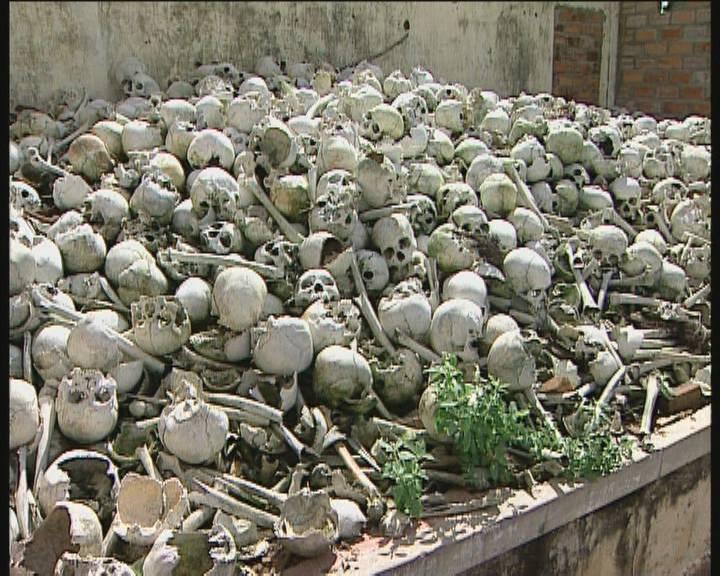

Programme 1 - Ordinary People: Victims of the Rwandan genocide

Programme 1 - Ordinary People: Victims of the Rwandan genocide

Programme 1 - Ordinary People: Memorial to victims of the Cambodian genocide

Programme 1 - Ordinary People: Memorial to victims of the Cambodian genocide

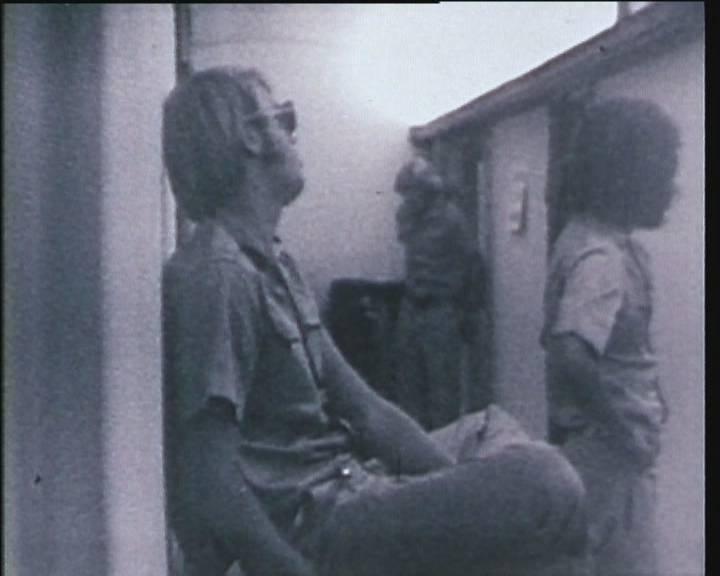

Programme 2 - Torturers: Scene from the Stanford Prison Experiment

Programme 2 - Torturers: Scene from the Stanford Prison Experiment

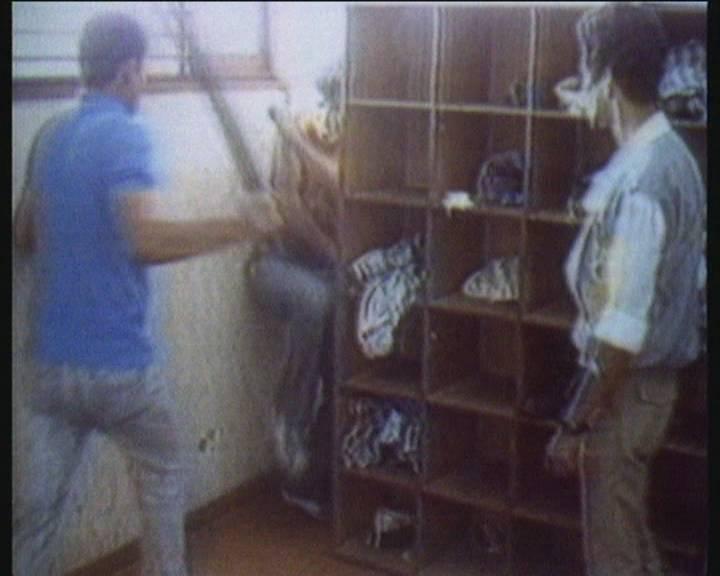

Programme 2 - Torturers: Victim of torture in Brazilian police station

Programme 2 - Torturers: Victim of torture in Brazilian police station

Programme 2 - Torturers: Palestinian in Israeli custody

Programme 2 - Torturers: Palestinian in Israeli custody

Programme 3 - Tyrants: Idi Amin

Programme 3 - Tyrants: Idi Amin

Programme 3 - Tyrants: Saddam Hussein

Programme 3 - Tyrants: Saddam Hussein

Programme 3 - Tyrants: Pol Pot

Programme 3 - Tyrants: Pol Pot

Title

Title

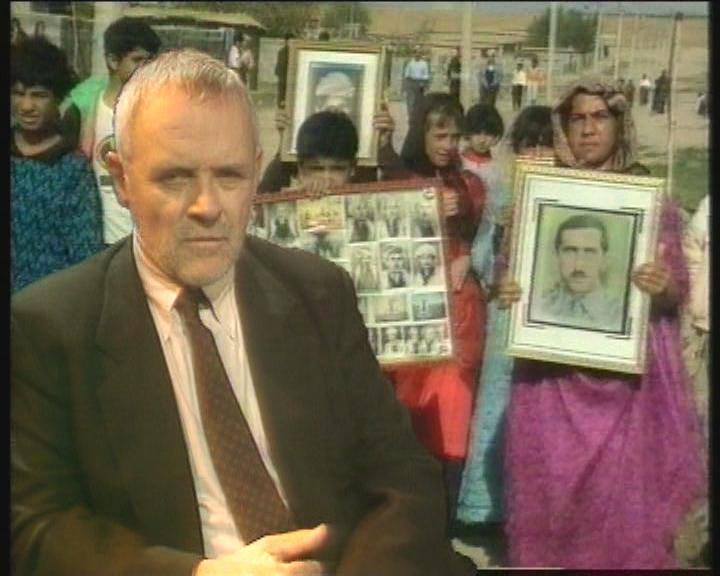

Sir Anthony Hopkins presents a programme on disappearance

Sir Anthony Hopkins presents a programme on disappearance

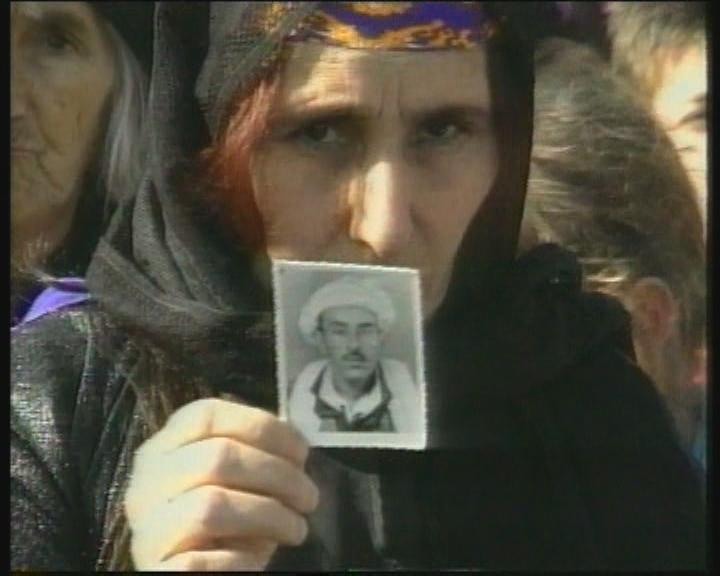

Mothers of the Disappeared in Iraq

Mothers of the Disappeared in Iraq

Mothers of the Disappeared in Iraq

Mothers of the Disappeared in Iraq

Kurdish victims of the Anfal Genocide carried out by Saddam Hussein's regime in Iraq

Kurdish victims of the Anfal Genocide carried out by Saddam Hussein's regime in Iraq

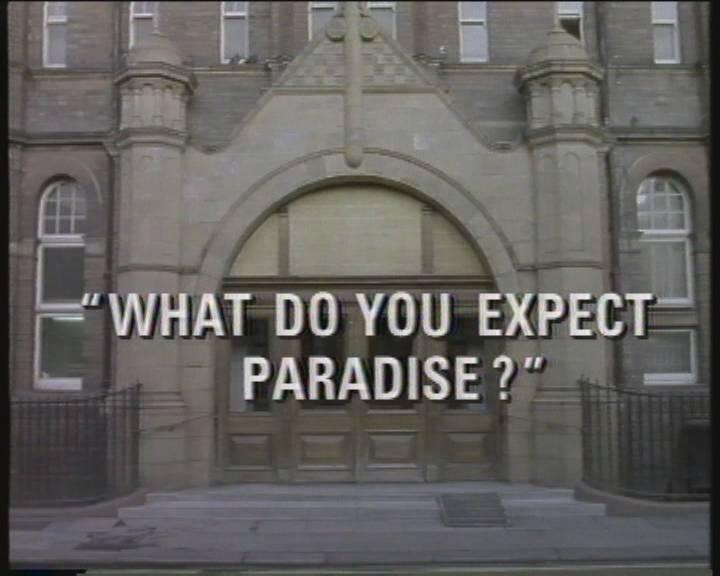

Title

Title

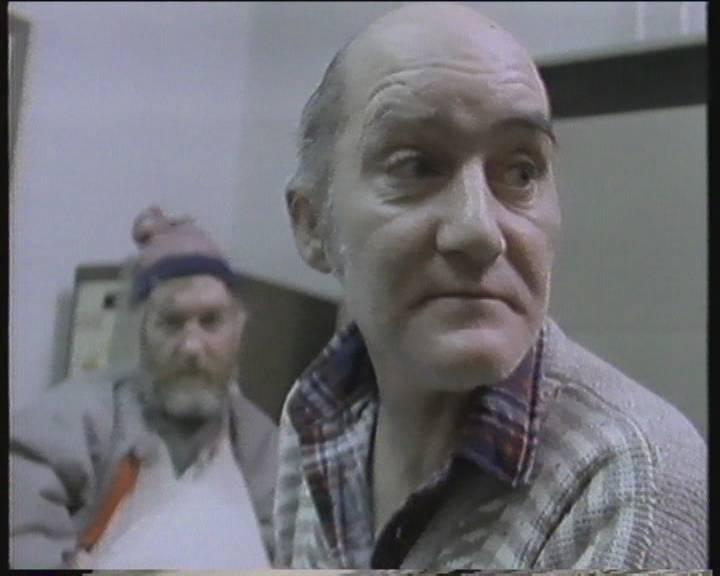

Gerry, resident of Arlington House

Gerry, resident of Arlington House

Jim, resident of Arlington House

Jim, resident of Arlington House

Lou, resident of Arlington House

Lou, resident of Arlington House

Residents of Arlington House

Residents of Arlington House

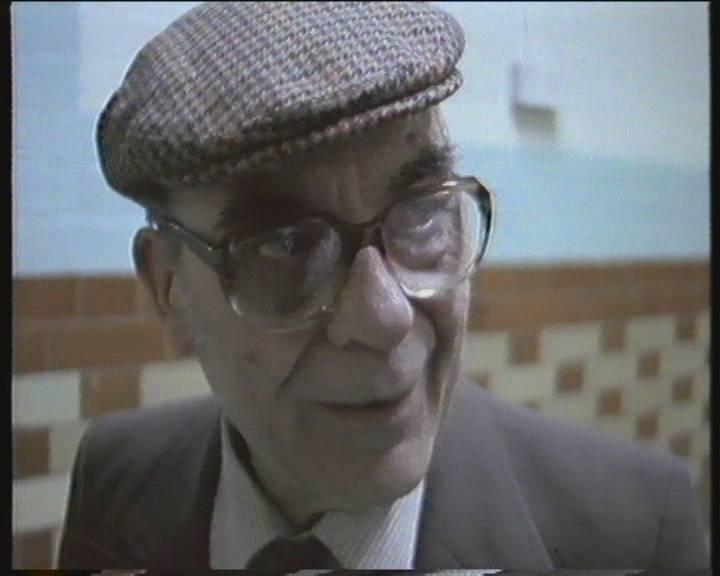

James, Arlington House's oldest resident

James, Arlington House's oldest resident

John, resident of Arlington House

John, resident of Arlington House

Arlington House set in Camden Town North London

Arlington House set in Camden Town North London

Title Card

Title Card

Sting presents the case of South Korean student Soh Sung

Sting presents the case of South Korean student Soh Sung

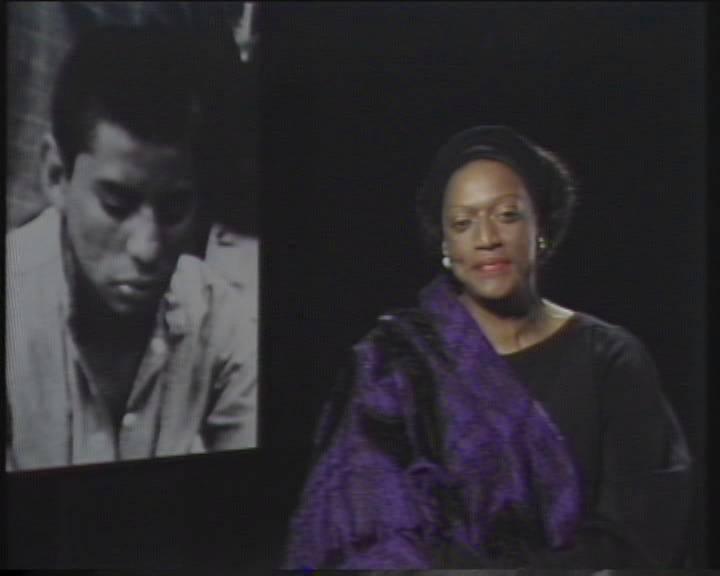

Jesse Norman presents the case of a Guatemalan street child

Jesse Norman presents the case of a Guatemalan street child

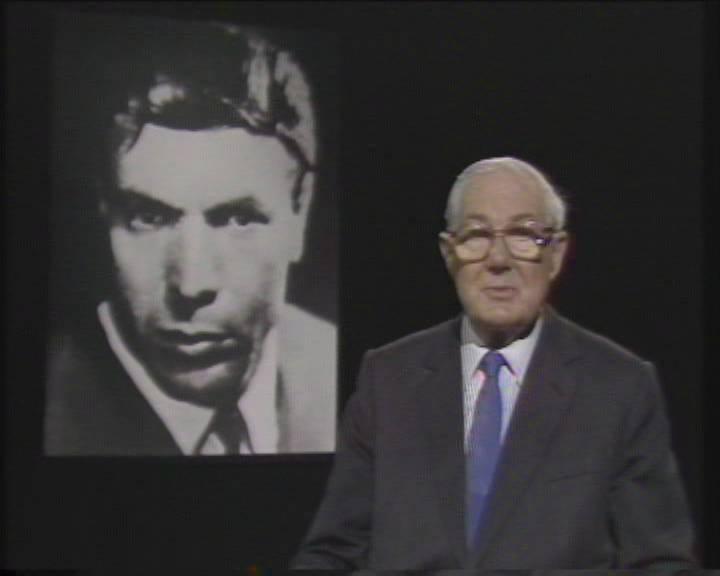

Lord Callaghan presents the case of Soviet dissident Mikhail Kukabaka

Lord Callaghan presents the case of Soviet dissident Mikhail Kukabaka

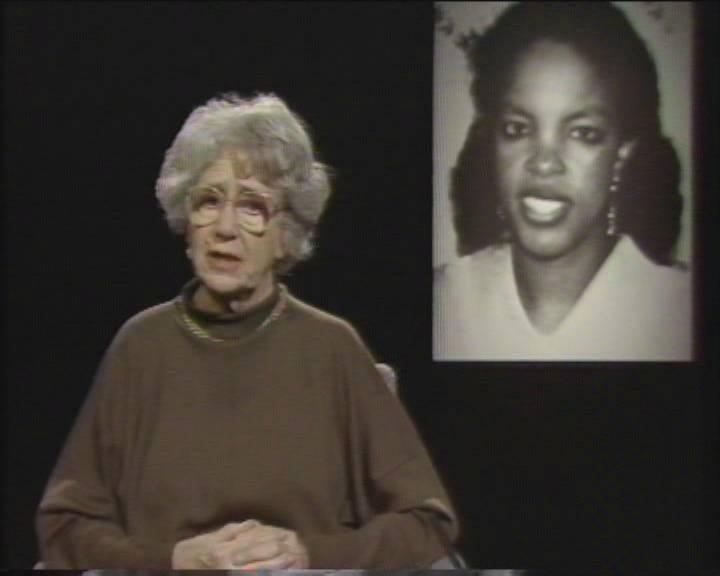

Dame Peggy Ashcroft presents the case of Somali doctor Safia Hashi Madar

Dame Peggy Ashcroft presents the case of Somali doctor Safia Hashi Madar

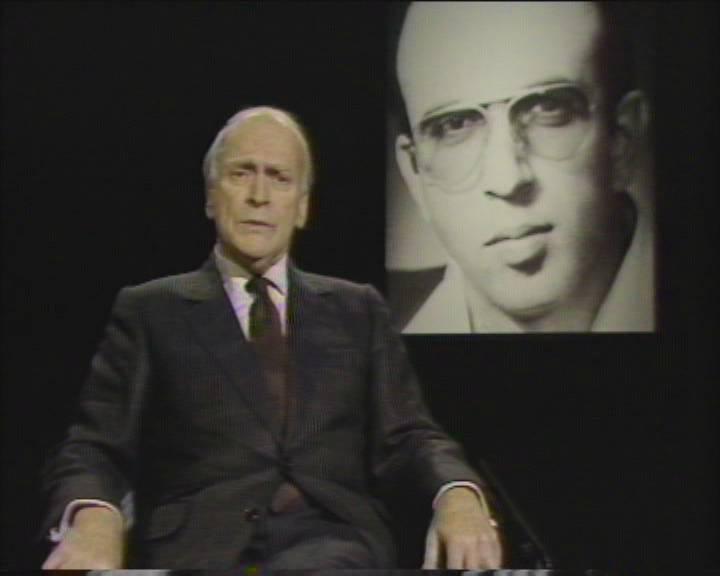

Yehudi Menhuin presents the case of the Palestinian Dr Jad Itzak

Yehudi Menhuin presents the case of the Palestinian Dr Jad Itzak

Title Card

Title Card

Martin Luther King and family

Martin Luther King and family

Banner illustrating racial hatred

Banner illustrating racial hatred

The oratory of Martin Luther King

The oratory of Martin Luther King

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Victim of Chicago gang violence

Victim of Chicago gang violence

Afro american students

Afro american students

Martin Luther King in Chicago

Martin Luther King in Chicago

USA's Stealth Bomber

USA's Stealth Bomber

Sales video

Sales video

Salesman demonstrating the Oerlikon Anti Aircraft gun

Salesman demonstrating the Oerlikon Anti Aircraft gun

Salesman demonstrating portable missile launcher

Salesman demonstrating portable missile launcher

Title

Title

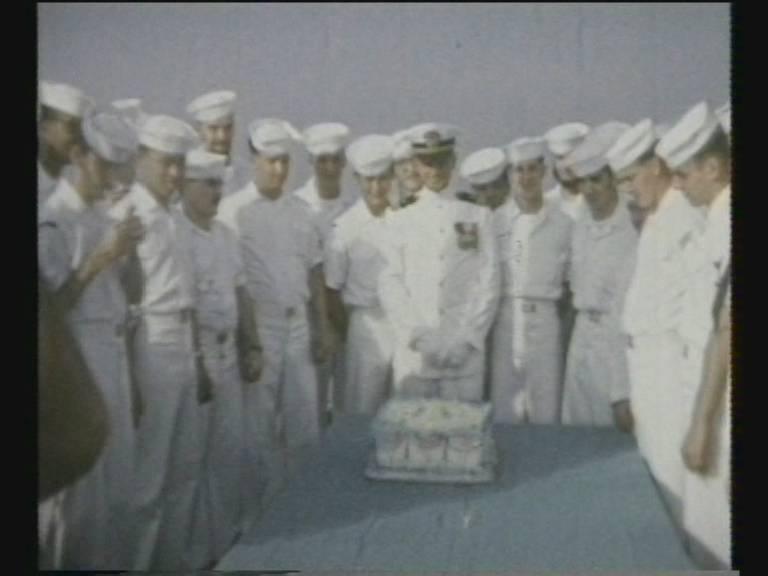

Crew of the Liberty

Crew of the Liberty

Wounded sailor after the attack

Wounded sailor after the attack

Former Admiral of the Israeli Navy Shlomo Errell

Former Admiral of the Israeli Navy Shlomo Errell

US Survivor of the attack

US Survivor of the attack

Rescue after the attack

Rescue after the attack

Ex-soldiers practising torture techniques, USA

Ex-soldiers practising torture techniques, USA

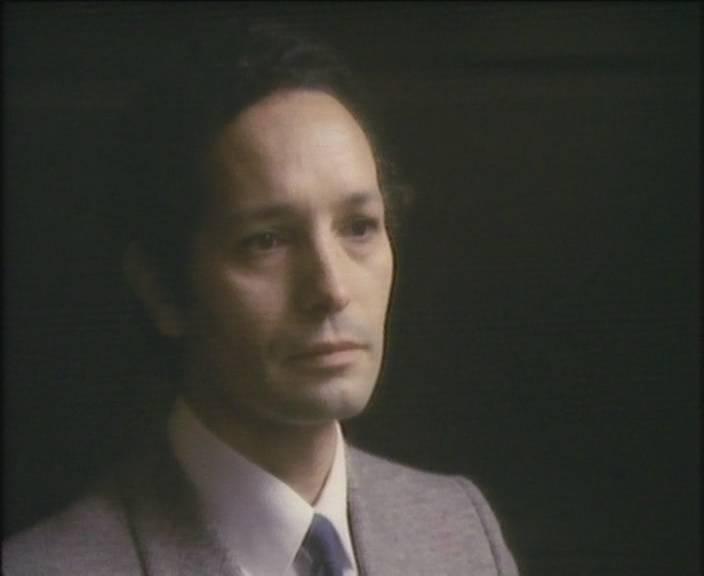

Torturer

Torturer

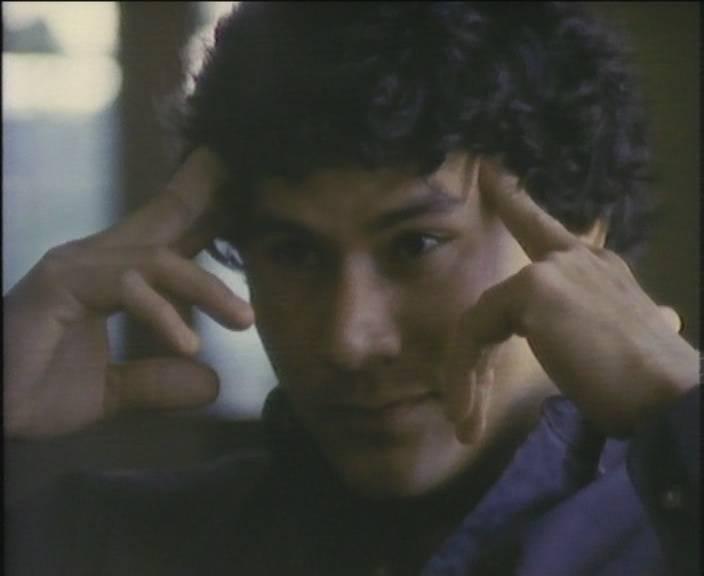

Victim illustrating torture technique used on him

Victim illustrating torture technique used on him

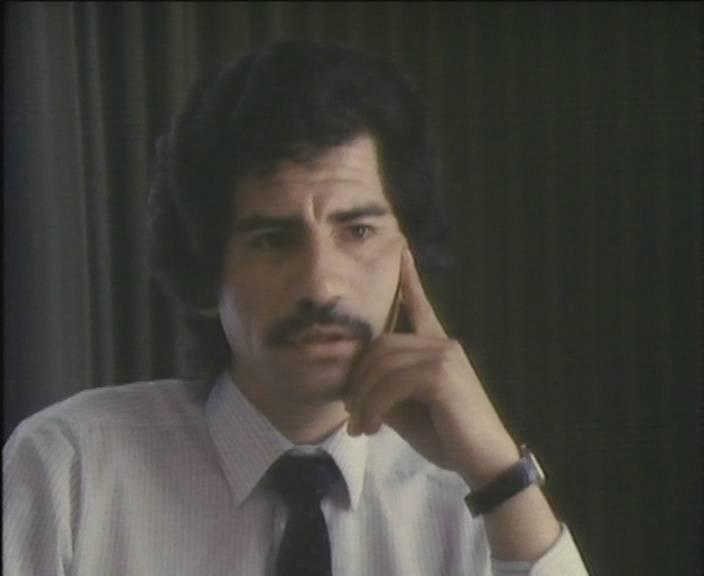

Chilean ex-torturer

Chilean ex-torturer

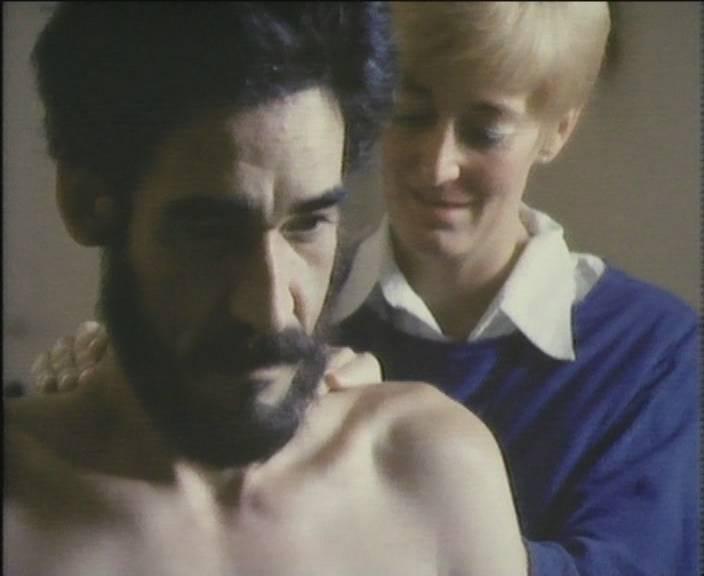

Victim of torture receiving treatment

Victim of torture receiving treatment

Depiction of torture

Depiction of torture

Rene Hurtado, Salvadorean ex-torturer

Rene Hurtado, Salvadorean ex-torturer

Otman Otmani, Tunisian torture victim

Otman Otmani, Tunisian torture victim

United Nations Human Rights Commission in session

United Nations Human Rights Commission in session

Survivors of human rights abuses in Sudan

Survivors of human rights abuses in Sudan

Sudan

Sudan

Amputee victim of Sharia law, Sudan

Amputee victim of Sharia law, Sudan

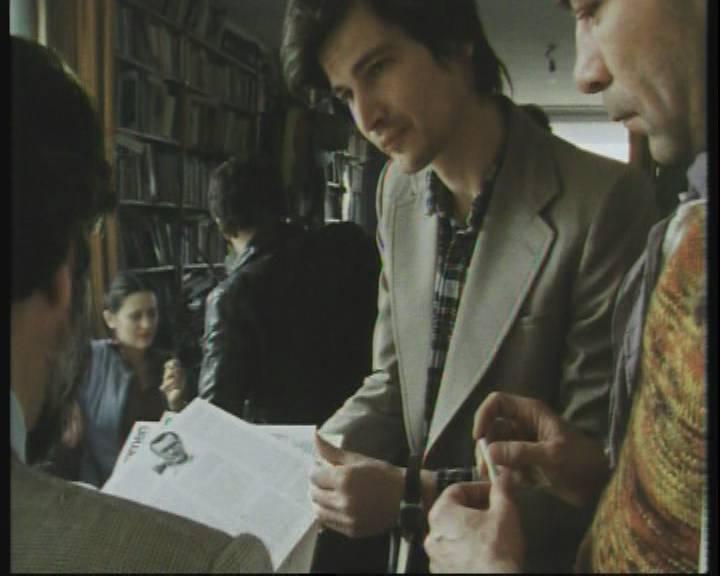

Hungarian dissidents

Hungarian dissidents

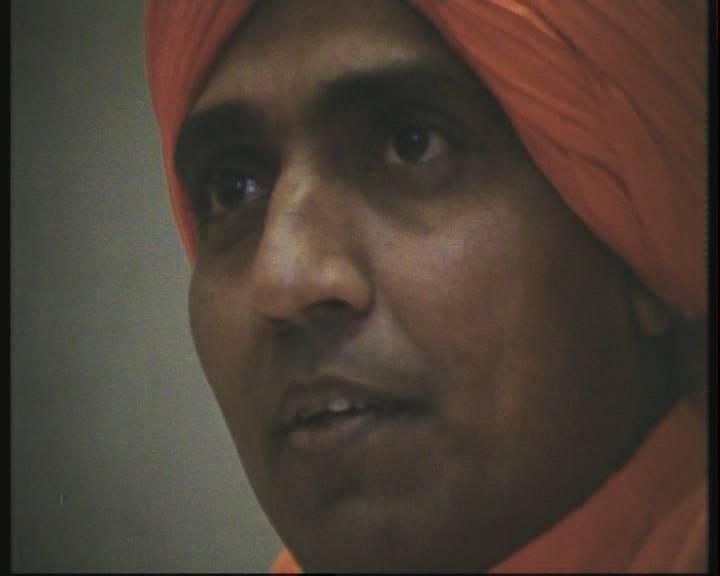

Swami campaigning for the rights of tribal peoples

Swami campaigning for the rights of tribal peoples

Lord Colville, UN Rapporteur for Guatemala

Lord Colville, UN Rapporteur for Guatemala

European Court of Human Rights in session

European Court of Human Rights in session