REXENTERTAINMENT

“The phrase that I have come to believe best sums up what the documentary film can most hope for, is to ‘undermine the simplicities’. The challenge is to present a much needed sense of flawed humanity not stereotypes.”

Rex Bloomstein

Rex Bloomstein has made over 150 single films, television documentaries and series and, in January 2012, presented his first radio documentary, Dying Inside for Radio 4. He is currently developing a number of further projects.

For full details about his work, follow the links below.

This is a film about hope.

The hope experienced by prisoners who, written off by society, have been thrown a lifeline and offered a path away from criminality and back towards redemption and normality.

At its heart it confronts stereotypes and public perceptions of ‘The Offender’ by presenting both serving and ex-prisoners as real people with real problems. Crime can ruin lives – of the victims, of course, but also of the perpetrators who not only have to deal with their own feelings of guilt, but are also then stigmatized by society, making it difficult for them to recover from what they have done, even after they have completed their sentence. Lacking support, many inevitably re-offend.

The vicious cycle of re-offending rates is an urgent story of our time. The figures are stark.

Almost two thirds of those released from the UK’s prisons are convicted of another crime within 12 months if they fail to find a job – 50 per cent more than those who do find work. Re-offending costs the UK tax-payer an estimated £15 billion a year. And yet the vast majority of employers openly admit they will not employ an ex-offender.

There are exceptions.

Embedded in a number of UK prisons are training academies run by Timpson, a leading high street retailer specializing in shoe repairs, key cutting and engraving, as well as photo processing through its subsidiary, Max Spielmann.

Timpson have forged new ideas in the recruitment of ex-offenders and now employ over 600 up and down the country. Their pioneering prison academies offer hope in exchange for hard work to a selection of inmates coming to the end of their sentences. All are fascinating because of the challenge to prisoners, both career criminals and first timers, to seize this opportunity to change the course of their lives.

This 90-minute feature documentary accompanies two serving prisoners on their journeys through this unique training programme – each with a genuine chance of employment on their release, if – and it is if – they don’t mess up the opportunity.

These journeys are punctuated by encounters with four former prisoners, now Timpson and Max Spielmann employees, who have embraced the world of work and are now living normally outside the walls.

These are vignettes of real lives, we see them at home and at work, interacting with customers and taking pride in their jobs. Reflecting on their own journeys from criminality to hard graft and an honest wage they delve into their backgrounds, their crimes and their regrets; their experiences in prison and how they grasped the opportunity to re-train. They relive the crucial moments that transformed their lives – those moments that led to hope, change and ultimately to redemption.

A Second Chance is a unique glimpse of lives regained. Instead of simply presenting the familiar bleak universe of the prison system, this is a film that documents the transformative power of work for those who want to change, the importance of employment as well as of forgiveness and remorse.

I have made many films about the UK prison system over the last 40 years or so.

Now, in 2019, the crisis it faces in terms of overcrowding, violence and re-offending is unprecedented. And yet, as a society, we remain addicted to imprisonment.

With over 90,000 men and women crammed into around 140 jails, Britain has the third largest prison population in the whole of Europe – behind only Russia and Turkey. And the trend is upwards.

If we are to reverse this – and it currently costs the taxpayer over £40,000 a year for every single person behind bars – attitudes have to change. Attitudes towards not only who should be in prison and the kinds of crimes that need to be punished by locking someone up, but also how to begin the process of rehabilitation so that convicted men and women don’t re-offend, don’t find themselves back inside, and instead make that choice to rebuild their lives after release back into society.

The truth remains that most prisoners leave custody with no job and, dogged by the stigma of their sentence, little prospect of finding one. Many have lost their homes and almost everything they possessed. How can they possibly put their lives back together?

With no money, no income and precious little hope, for too many it’s simply too easy to return to drug abuse, to criminality and, almost inevitably, to prison. But not all offenders should be written off and many deserve a second chance – for their own good and for the good of us all.

I met James Timpson, Chief Executive of the Timpson Group, through our work with the Prison Reform Trust. When he told me that, unlike the vast majority of employers, he has made ex-offenders a major source of recruitment and has even opened training academies inside some prisons, I began to explore the idea of making a film about some of these trainees as well as former prisoners now working in Timpson’s.

The more I researched, interviewed and listened to a variety of serving prisoners and ex-offenders – people whose lives, for whatever reason, had been so impacted by their descent into criminality – the more I recognized that work can be a key component to rehabilitation. It can restore a sense of pride and self-worth as well as providing that all important income and sense of stability.

And, as employers like Timpson have discovered, the benefits to offering this second chance to offenders genuinely outweigh the risks. Many are former career criminals and not all are a success, but those I met who really wanted to change their lives told me how much it meant to have this opportunity to turn away from a criminal path.

What greater challenge could there be for those who have offended against society? The challenge to return to society, and gain self-respect through work.

In the face of so many negative factors and reports on the prison system, this film has been a rare opportunity to tell a more positive story of what can and should be achieved. It also reveals how devastating the temptations of crime can be for the person caught up in criminality and for their families.

My hope is that A Second Chance will do as our title suggests, become a catalyst for breaking down perceptions, challenging stereotypes and opening the eyes of the public, employers and the prison system itself to the importance of work as a key to tackling the profound problem of re-offending.

The Guardian, Eric Allison

At a time when the prison system is in meltdown and reformers in despair, [A Second Chance] offers a glimpse of hope and inspiration and, above all, shows what can and should be done if we are to make headway in the battle against reoffending… This absorbing film sends the message out – quietly but clearly. The prime minister would do well to listen.

We decided to re-edit the end of the film because of the great news of Zarganar’s release from jail in late 2011. We all met in London in 2012 and filmed our encounter. This then became the basis of this new version, which is now 75 minutes long.

On completing This Prison Where I Live in mid-2010 we joined with several NGOs and human rights groups to form the Free Zarganar Campaign. As part of this campaign, the film was screened in more than 30 different countries over the course of the following 12 months.

But Burma was beginning to change. The ruling military elite was edging tentatively towards democracy and, on 12th October 2011, we were finally able to celebrate as Zarganar became one of the first political prisoners to be released. This was six weeks after the Democratic Voice of Burma broadcast the film illegally into the country on its satellite channel.

A few months later he was allowed to leave the country to be reunited with his family in the US. And then he came to Britain.

We were waiting.

The updated version of This Prison Where I Live is a slightly tighter, 75-minute cut, which includes six minutes of new footage filmed on the day Michael Mittermeier and I caught up with Zarganar in London. For Michael, it was a first meeting with a man he had admired from afar, but thought he may never see in person.

Zarganar told us how he had watched a copy of This Prison Where I Live smuggled into prison before his release and revealed that Burma’s president, Thein Sein, had also watched the film - and, bizarrely, said he liked it! Zarganar felt the broadcast of the film was a significant factor in hastening his release.

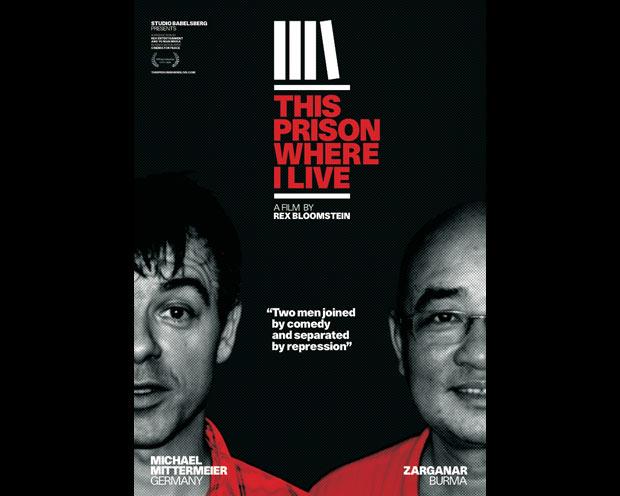

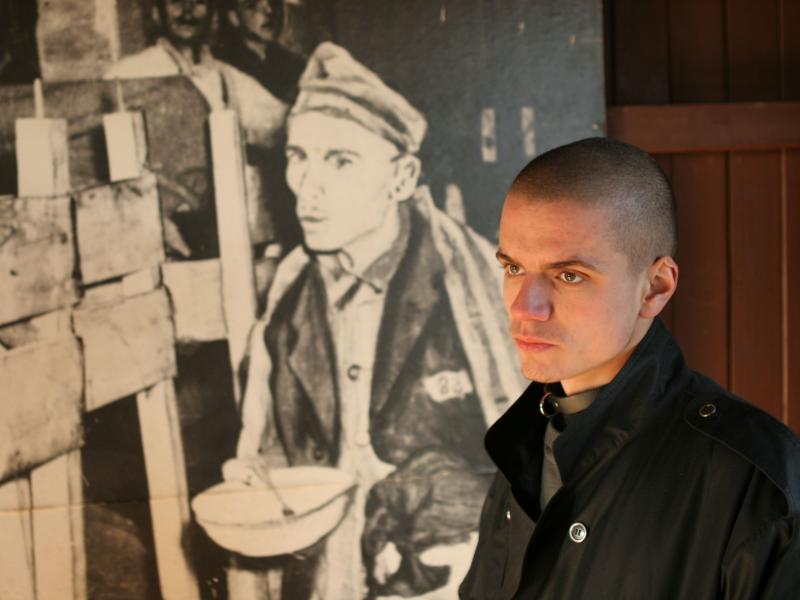

This is a film about two comedians.

Zarganar is Burma’s greatest living comic. Relentlessly victimised by the military junta, in 2008 he was sentenced to 35 years in prison – silenced for his outspoken criticism of the ruling generals. Michael Mittermeier, in stark contrast, is free to practise as one of Germany’s leading stand up comedians.

Two men joined by comedy and separated by repression.

The genesis of this film begins in 2007, when Zarganar agreed to be interviewed by documentary filmmaker, Rex Bloomstein, despite being banned from all forms of artistic activity and talking to foreign media. Over two days Bloomstein and his team interviewed Zarganar in depth in his flat, and were shown the cinemas that are prevented from screening his films, the bookstalls not allowed to sell his plays or poetry, and the makeshift TV studio where his fellow comedians rehearse on a stage that he himself is forbidden to tread.

Hearing of Zarganar’s fate and seeing this footage, Michael Mittermeier joined with Rex Bloomstein to make a film about this courageous man, who has paid such a price for speaking out against the regime. Together with a small team, they travelled secretly to Burma in 2010 to document his struggle against repression and to investigate humour under dictatorship.

This Prison Where I Live is a feature documentary and is the story of Michael’s exploration into the personality, the motivation and the talent of a man who describes himself as the ‘loudspeaker’ for his people.

I arrived in Rangoon, the former capital of Burma, in April 2007 to begin a journey to Mandalay for An Independent Mind, my feature documentary on the struggle for freedom of expression in different parts of the world.

Before we left to travel north, our contacts had arranged for us to film a man who was banned from producing, directing or acting, banned from any performance on stage, banned from talking to any foreign media, banned from writing in any journal or magazine; the very mention of his name totally forbidden.

It was Zarganar, Burma’s leading comedian.

We secretly filmed this extraordinary man for two days – at great risk to himself. This footage remained unused. So when, two years later, I heard that he had been sentenced to 35 years in prison, I was determined to make a film that would reveal this wonderful comic personality. A film that would share, as I had shared, his thoughts and feelings, his stories of arrest and torture, how he had survived five years of solitary confinement. I wanted the world to experience his humility, his identification with the ordinary people of Burma and his fearless opposition to the Generals. I also wanted people to hear his response to the years of persecution he had suffered at their hands, when he turned to me on camera and said, “my enemy must be my friend.”

It was the great German comedian, Michael Mittermeier, who made this film possible. I decided to tell the story of how it came into being and the decision Michael and I made to go to Burma. We wanted to get as near to Zarganar as we possibly could and show the world the prison he was in. But it was also important to reveal the problems we encountered, the questions we had to ask ourselves about what we were doing, and why, and what harm might befall both us and the people who were helping us. It was they who had to live and survive day by day in a dictatorship. It is all there in the film along with excerpts from Zarganar’s movies and television appearances that we managed to smuggle out of the country.

Rex Bloomstein

“Maung Thura, better known as Zarganar, is considered to be Burma’s greatest comic. His outspoken opposition to the country’s military junta has led to 25 years imprisonment on the flimsiest of charges. The film contrasts the price he has paid for his role as the ‘loudspeaker’ for his people with the freedom of speech enjoyed by controversial German satirist Michael Mittermeier. A lengthy 2007 interview with Zarganar is at the heart of this thought-provoking documentary about state repression.” - THE DAILY EXPRESS, 4 stars

“A long prison sentence, we now know, can win you a Nobel Peace Prize. In nations light on human rights – whether China or in This Prison Where I Live, Burma – it can also win you a quixotic, captivating documentary. The poet and stand-up comic Zarganar, after years of satirising the military junta and after one previous jail spell, is now serving a 59-year sentence for treason. British filmmaker Rex Bloomstein logged an interview with him just before he was sent down and uses snippets as an extended prologue. The burly baldpate cracks jokes like hard-boiled eggs, while fully aware (we sense) that he may be the next egg to be cracked by fate.

The rest of the film narrates Bloomstein’s return to Burma, with German stand-up comedian and Zarganar fan Michael Mittermeier (who also produced the film) as a frontman. The focus is a bit muddled. The field trip’s programme starts falling through when Zarganar’s friends fail to honour interview appointments. (The junta has warned them off.) Finally – yet compellingly – Bloomstein and Mittermeier are reduced to contraband camerawork, taking drive-by shots of Zarganar’s prison from car and motorbike.

Are they in peril of arrest? Probably not. But these scenes stir some much-needed “action” into a film Beckettian, at times, with inanition. Waiting for Zarganar. Or perhaps, in weird kinship with wannabe biographer Ian Hamilton’s famous Salinger hunt, In Search of Zarganar. It’s a charming, courageous film even at its most maddening. Fittingly it ends with the appalling postscript – a parody of optimism fit for a military state – that Zarganar’s sentence has now been ‘reduced’ to 35 years.” - THE FINANCIAL TIMES

“[Zarganar is] probably the bravest comedian in the world. In the film, which features rare footage of him in conversation, he comes across as the humblest, too. Prevented from earning a living or even writing his own name, he explains, with smiling certainty, that it’s all part of the job description: ‘We must stand in front of the people – and sacrifice for the people’, he says’.” - THE DAILY TELEGRAPH, Dominic Cavendish

“Burmese comedian and film director Zarganar is currently serving a 35-year prison sentence for daring to criticise his country’s military dictatorship. This inspirational but somewhat meandering documentary melds the footage of British film-maker Rex Bloomstein, who interviewed Zarganar in 2007, with the story of a German comedian, Michael Mittermieier. They travelled together to Burma to secretly film an investigation into a humble, jovial but ferociously courageous figure. Although overlong and drifting, this film will make you seriously question whether you would stand up to injustice if the stakes were this high.” - METRO

“This Prison Where I Live is an eye-opening documentary about Zarganar, a Burmese comedian who director Rex Bloomstein met a couple of years ago in the authoritartian state. A mischievous, indomitable critic of the brutal military leadership, Zarganar was last year imprisoned for more than 50 years for making some mildly disparaging remarks about the regime to foreign press. Attempting to discover what exactly has happened to Zarganar, Bloomstein returns to Burma with Michael Mittermeier, a successful German comedian (yes, they do exist). What unravels is a damning portrait of the extent of state censorship – no one will speak to Bloomstein, fearful of the repercussions – and a fierce indictment of a society that is compelled to lock up its comedians. There’s plenty of archive footage of Zarganar, and while his humour struggles to transcend cultural barriers, his impish and jovial presence lights up the screen.” - THE BIG ISSUE

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Article 19

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

How do you deal with the threat of imprisonment for drawing a cartoon of your president? How do you survive being sent to a labour camp for telling a joke? What is the impact of being tortured for writing a poem? Or of being forced into exile for singing a song?

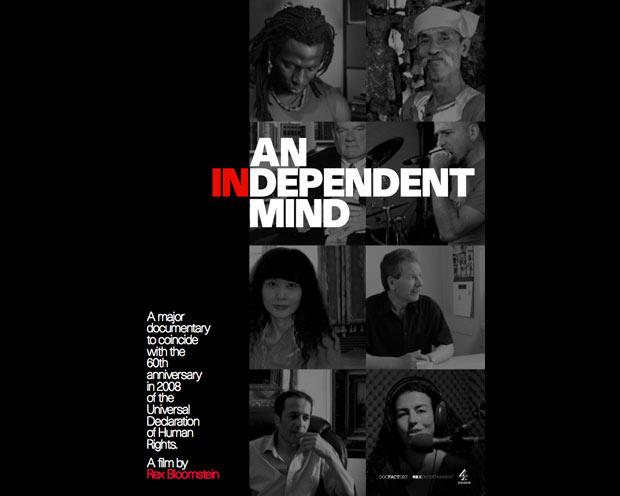

These are some of the stories you will encounter in AN INDEPENDENT MIND, a unique feature-length documentary inspired by one of the most fundamental and controversial of human rights: Freedom of Expression.

Through encounters with a succession of eight different characters attempting to exercise their right to freely express themselves in different parts of the world, the film explores in human terms the importance and complexities of freedom of expression and its acceptable limits. Eight individual voices that together magnify one profound central theme.

Above all, it is a film that will make you reflect – on the importance of the free dissemination of knowledge, opinion, art and, significantly, its limits.

From a research list of well over a hundred different cases from all over the world I chose eight different characters. These stories follow one from another. They are not inter-cut, each is self-contained and each character speaks for themselves. There is no commentary. I have endeavoured to be non-judgmental, to present each individual to the audience as they presented themselves to me.

Freedom of expression is a cornerstone right but it is not an absolute right. Under international law, it is subject to restrictions on certain grounds, such as national security, morality, protection of an individual’s reputation, or incitement to violence.

But these limits and restrictions are rarely clear-cut. How are they defined? How open to abuse are they? Should freedom of expression include the freedom to say unpopular things? Is freedom of expression a luxury in the modern world?

Through AN INDEPENDENT MIND I want to encourage our audience to reflect on these questions by seeing people who are actually dealing with the consequences of living their lives as artists and thinkers. This is a film that allows us to glimpse their realities as people who are exploring, confronting and commenting on their societies. Through them, I hope we can reflect on the importance of freedom of expression, its complexities and challenges and limits.

I wanted this to be as global an exercise as possible. It would have been easy to focus on certain parts of the developing world, while ignoring our own Western democracies. But we are also seeing a gradual erosion of this freedom in the West through the broadening in scope of what is deemed ‘unacceptable speech’.

This is an age of extraordinary mass communication, when all the different forms of modern media should, on the face of it, be giving an opportunity for anybody to freely express themselves, yet Article 19 seems to be an area that is increasingly bitterly contested.

AN INDEPENDENT MIND is a film for our time.

Rex Bloomstein

“This Wednesday, it will be 50 years since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly. On the eve of that anniversary, Rex Bloomstein’s new documentary, An Independent Mind, follows eight very different people from around the world as they fight for their freedom of expression.

The subjects range from the exiled Ivory Coast singer Tiken Jah Fakoly to the Chinese sex-blogger Mu Zimei; from Burma’s political comedians the Moustache Brothers to the British historian David Irving, who has been accused of being a Holocaust denier in the past. Others include a Basque rock group, a Syrian writer and an Algerian cartoonist, all of whom have been imprisoned or silenced due to their beliefs. ‘These people are living with the consequences of their choice to speak,” says Bloomstein. ‘Through these lives, I hope that we will have a strong sense of just how vital that freedom is and the price that others will pay for it.’

Bloomstein’s film is unsettling. With no narrator to guide you or music to distract you, the stories speak for themselves, with often surprising consequences. David Irving, for example, who has written admiringly of Hitler, makes a convincing case against censorship. ‘He was very interesting indeed,’ says Bloomstein. ‘Being Jewish myself, my decision to include Irving could be seen as controversial. But I’m not supping with the Devil. I’m exploring someone who has often repellent views. Irving denies he’s a denier. Nevertheless, should he have been imprisoned? I’m not sure that he should. I happen to favour debate and challenging people like Irving.’

The director concedes, however, that ‘freedom of expression by itself cannot be unlimited. There should be a marketplace for ideas. The health of society is often determined by the width and breadth of opinions and the explorations that are available. And if people feel offended or threatened, then they must turn to the law’.

In the past, the director has won awards for his unflinching films about prisons and the Holocaust (including KZ and Kids Behind Bars). An Independent Mind is a similarly stirring, challenging piece of work. ‘I’m hoping that it will make people think about what society would be like without freedom of expression. It is a vital human right, and without it, we’re much diminished.’” – THE INDEPENDENT ON SUNDAY

“Rex Bloomstein’s thoughtful, subtle film asks what has become of one of the defining questions of our time… Excellent.” - GUARDIAN GUIDE

“Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that “everyone has the right to freedom of expression” and it’s this that drives Rex Bloomstein’s sober and reflective documentary…..Bloomstein believes that that those that seek to defend freedom of expression should do so in all quarters, however unpalatable the sentiments.” – THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

“’As soon as you start saying this opinion is accepted and acceptable and that opinion is not acceptable, then you are degrading society’. A laudable closing statement for this meaty film… “ – THE TIMES, DIGITAL CHOICE

“Marking the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Rex Bloomstein’s film raises issues of freedom of speech by letting various individuals relate their battle to express themselves.” – THE OBSERVER, DIGITAL PICK OF THE DAY

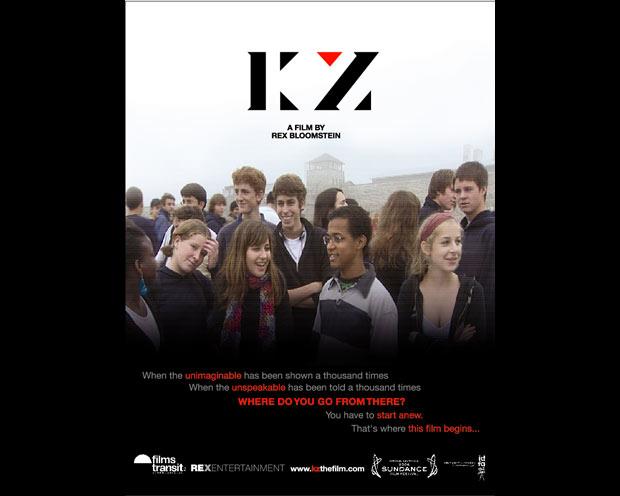

When the story of the unspeakable has been told a thousand times, when the images of the unimaginable have been shown a thousand times, when the mind is numb – where do you go from there? You have to start anew…

That is where this film begins.

On the banks of the river Danube, surrounded by the beautiful landscape of Upper Austria, lies the picturesque town of Mauthausen. Two kilometers from its town centre is a place that attracts bikers, busloads of tourists, parties of schoolchildren, people from all over the world. Tour guides come to work here every day, while nearby the locals go about their daily lives. This is a place where thousands upon thousands of people from over 30 nations were tortured and murdered. This site is the former KZ, German short for concentration camp. How does it feel to be a tourist at a former concentration camp?

How does it feel to work here as a guide, day in day out? How does it feel to live here as a local with the dark secrets of the past? And what of those who’ve chosen this town to be their new home?

This is a groundbreaking film about facing our ultimate demons. It is a contemporary yet timeless piece on the horrors that we have and always will be able to inflict on one another.

Stripped of the usual dramatic devices, survivor testimonies and archive footage this radical film shows nothing but says everything.

It will shake you to the core.

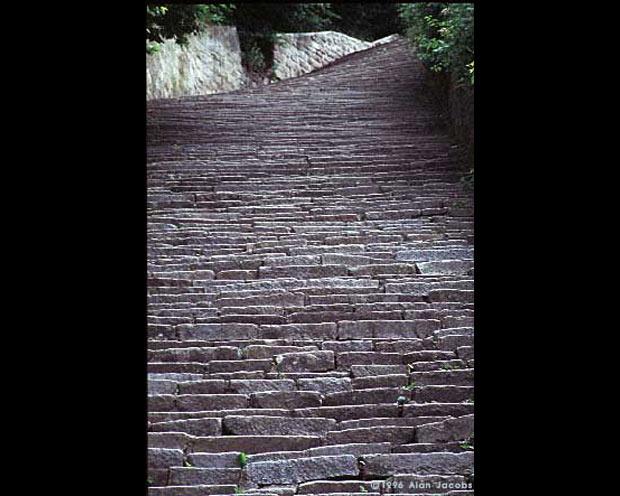

The oompah band played. Sausage and beer flowed. The men and women in lederhosen danced and sang. We’d broken for lunch and had stumbled across this typical pub party in rural Austria. Having eaten, we walked back some 400 hundred yards to the quarry in which we were filming - the main quarry where so many prisoners had been systematically worked to death only sixty years before. This was Mauthausen. It was 1995 and I had been making a film about the liberators of the Nazi concentration camps.

The disjunction of those two scenes remained with me – the carefree laughter of the pub garden and, a short walk away, the silence of the quarry.

Countless documentaries about the Holocaust have been made since the revelations sixty years ago of Auschwitz, Dachau, Belsen and Sobibor. There is talk of ‘Holocaust fatigue’ as if such a subject can ever be exhausted. What is true is that successive generations must find their own way to deal with the ‘tremendum’, as one philosopher has named it. For many questions continue to haunt any endeavor to understand the essence of the concentration camps. What are our reactions at the horror that engulfed millions? How can we respond to the incredible plan to obliterate every last Jewish man, woman and child from the face of the earth and dehumanize and enslave whole other races and groups of people?

Today thousands of people come from all over the world to visit Mauthausen, the largest Nazi concentration camp in Austria. Curious and compelled by what took place 60 years ago, they walk through the concrete buildings where the SS administered the camp, the inmate blocks that housed prisoners from all over Europe as well as American, British and Russian POW’s, the gas chamber and crematorium, the execution corner. They clamber up the 186 steps that prisoners were forced to climb with knapsacks full of bricks from the quarry.

What do they think?

What do they feel?

What are their questions?

This is our focus: the tourists, the sightseers, the curious wandering about the camp; those who have come specifically; the tour guides leading groups of school children and parties of older people; Mauthauseners going about their daily lives; Mauthauseners who were young at the time; and those who have become Mauthauseners by deciding to move to the area.

As the project developed I realized that the film had to be more austere in its approach and that I would have to jettison most of the fashionable tools of documentary filmmaking. So there is no commentary, no music, and no reconstructions with actors.

KZ is stripped down. There is no attempt to sentimentalize or overtly manipulate the emotions. There are no historians; there is no black and white footage of the liberation of the camp, no piles of corpses. All have been seen. It is in the reactions of the guides, the visitors, young and old, that the challenge lies. It is in the universality of that experience.

KZ is probably the first 21st century film on the Holocaust without survivors and as such it presages the future.

KZ is a film about the interface between now and then. What do the meanings of the camp experience convey to all of us who were never there? How possible is it for our imagination to grasp the enormity of the crimes committed there. Why should we consider these events when we have our own contemporary genocides and wars?

KZ is a film that it is set in the landscape of a concentration camp but is a film about today, a film about us.

What will we remember?

In the Gulag Archipelago, Alexander Solzhenitsen wrote “If only there were evil people somewhere, insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?”

Rex Bloomstein

“Documentaries about the Holocaust tend to draw heavily on survivor testimony and archive footage in a doomed attempt to convey the ineffable, the most celebrated being Claude Lanzmann’s ‘Shoah’. With KZ, director Rex Bloomstein adopts a different approach, creating something quietly insightful and unsettling. While shooting an earlier film in the Austrian village of Mauthausen, site of a former concentration camp now refashioned into a grim tourist attraction, Bloomstein was struck by the contrast between the gruesome reality of the camp and the neighbouring village idyll. KZ explores how people live and cope with an historical trauma that occurred on their doorsteps, and their capacity to learn from those events.

Such toxic subject matter inevitable produces disquieting moments. As the camera tracks several guided tours through the camp, neither they nor the viewer is spared any of the details of what happened there by the zealous tour guides (one girl is so disturbed she faints). The tension peaks in the gas chamber, where a commemorative plaque has been defaced with a swastika. Throughout these claustrophobic sequences, Bloomstein trains his camera closely and almost exclusively on the shell-shocked visitors’ faces, which in turn compels the viewer to examine their own responses. Outdoors, the wind-strafed camp is absorbed in long takes, which build an effectively brooding atmosphere. Emergent visitors proffer many motives for their visit, ranging from religious empathy down to box-ticking on a tourist schedule. “It’s very nice here,’ enthuses one, who looks forward to visiting Auschwitz the following year.

These scenes are delicately crosscut with footage filmed in the local village, where interviewees’ responses are more varied and complex. A young couple evince little concern about living in a house once owned by an SS officer who worked at the camp, regarding it simply as a piece of prime real estate. An elderly man waxes nostalgic about the ‘beautiful time’ he had in the Hitler Youth. One elderly woman recounts the ‘beautiful wedding’ she attended in the camp. Not all the village elders are so insensitive, but the general tight-lipped reluctance to dwell on the past builds and overriding impression of denial, willed amnesia or indifference.

As Bloomstein roves the village his camera alights on fascinating details. The McDonald’s logo next to the sign directing the way to the camp is ….

… of course, Austrian himself, and he fetished exactly this brand of twee, folksy culture into a major plank of Nazi ideology. Austria, however, has never really admitted its culpability for Nazi-era war crimes, preferring to see itself as a victim.

That sense of denial is surely one aspect of what motivates the tour guides. All of them had grandfathers in the SS; there’s a strong sense of expiating a lingering sin. The most wracked figure is an alcoholic, whose marriage is breaking down partly because all he talks and thinks about is the camp. Clearly such sensitivity and openness to the past can be dangerous on a personal level. ‘We’re all sick up here,’ the man concludes. In the most resonant scene, Bloomstein shadows him as he does his round of the camp at closing time, just as dusk is falling, and tunes into an atmosphere of palpable dread. At such moments the camp seems like the psychic equivalent of a nuclear reactor, radiating its negative influence across generations and still capable of wreaking enormous damage on individual lives. Bloomstein’s film carefully marshals a polyphony of responses to the camp’s disfiguring presence, and the stark aesthetic - there is no music, narrative commentary or ‘expert’ testimony - feels entirely of a piece with the film’s refusal to pass judgement or draw conclusions. KZ is a beautifully understated, troubling achievement, one haunted by the necessary burden as well as the limits of memorialisation.” – SIGHT AND SOUND , Kieron Corless

“In its deceptively calm way, KZ is the year’s most fascinating documentary.” – THE INDEPENDENT ON SUNDAY

“KZ…is an outstanding documentary.” – THE OBSERVER

“…it raises issues of remembrance, and forgetting in a steadily unsettling, powerfully understated way.” – THE TIMES, 4 stars

“Rex Bloomstein achieves the impressive feat of not merely memorialising the Holocaust, but probing the complex, discomfiting hold it continues to have on the now.” – TIME OUT, 4 stars

“If it weren’t true you simply wouldn’t believe it…an impressively calm documentary.” – EVENING STANDARD, 4 stars

“Rex Bloomstein’s powerful documentary about the WW2 Nazi Mauthausen concentration camp centres on guides taking tourists around the camp (there is no archive footage), and his stark account still chills to the bone.” – THE DAILY STAR

“Britain Shines at Sundance”

“KZ ambitiously aims to create a radically different Holocaust film….. admirable work.” – THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

“Sundance Film Festival”

“quietly electrifying…. KZ reinvigorates oft-told Holocaust atrocities by relaying them from neglected perspectives.” – NEWSDAY

“Subtle and understated - but this only serves to make the film all the more unsettling.” – SCREEN INTERNATIONAL

“Committed Brit docu-helmer Rex Bloomstein continues his career long engagement with … KZ … increasingly disturbing portrait of contempo guides and visitors at the Nazi concentration camp Mauthausen, and villagers in the Austrian town. Strong subject and unfussy execution … Tech package is pro … Overlapping sound subtly knits together disparate scenes to impressive fluency and narrative flow.” – VARIETY

“Sublime … KZ becomes a fascinating study of the way minds work when confronted with the inconceivable.” – SALT LAKE WEEKLY, 3 ½ stars: favourable

“KZ is a totally engrossing and extremely disturbing doc….a powerful message delivered in an intriguing way.” – FILMTHREAT.COM, 4 stars: highly favourable

Critic’s Diary: “Rex Bloomstein’s powerfully restrained KZ makes a compelling case for not just the continued existence of the form itself, but the necessity of the concentration camp memorial experience.” – INDIEWIRE

“KZ, perhaps the first postmodern Holocaust movie … explores the subject in a different way. … Bloomstein … was making a TV documentary called “Liberation” when he noticed the beer drinking and singing taking place within yards of the former concentration camp. He was ‘haunted by the disjunction, the reality of people enjoying themselves, and then the reality over there’ at the camp, and decided to make a film that would show ‘the interface of memory and history and the present’.” - JEWISH JOURNAL

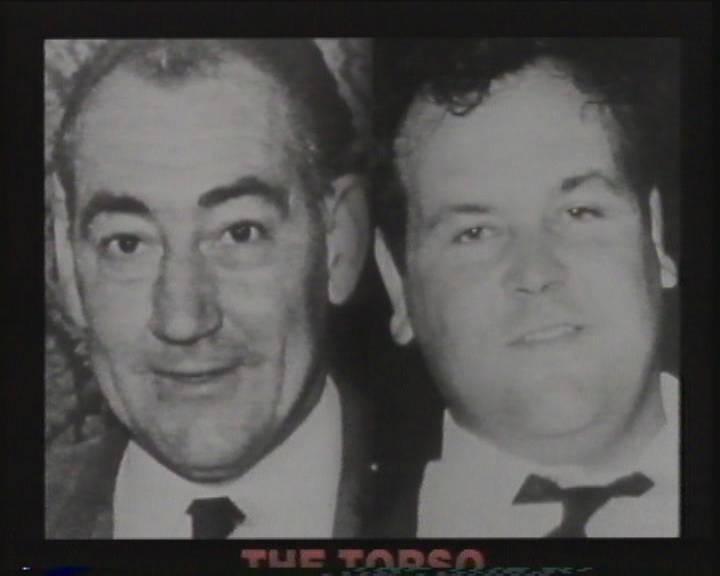

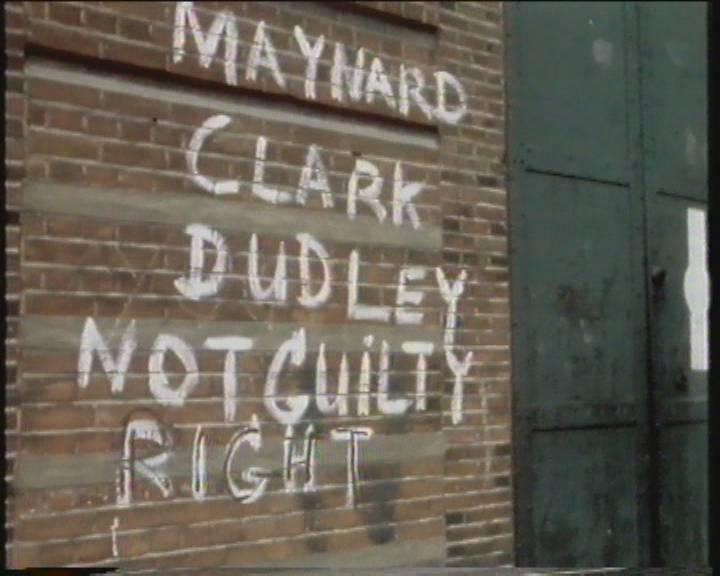

I had become aware of the campaign that Duncan Campbell, the Guardian journalist, had waged on behalf of Reg Dudley and Bob Maynard, career criminals who were convicted of of a double murder in the 1970s and both given life sentences after the longest murder trial in British legal history. Duncan was convinced, as were other journalists, that they were both victims of a miscarriage of justice - such cases were not uncommon at that time. After studying the case myself, I also became convinced of their innocence and approached Channel 4, who agreed to commission the film. Some years later their sentences were quashed by the court of Appeal and they were given compensation. Reg Dudley, who I had filmed for my Lifer programme in the early eighties, has since died.

“The same, only torso

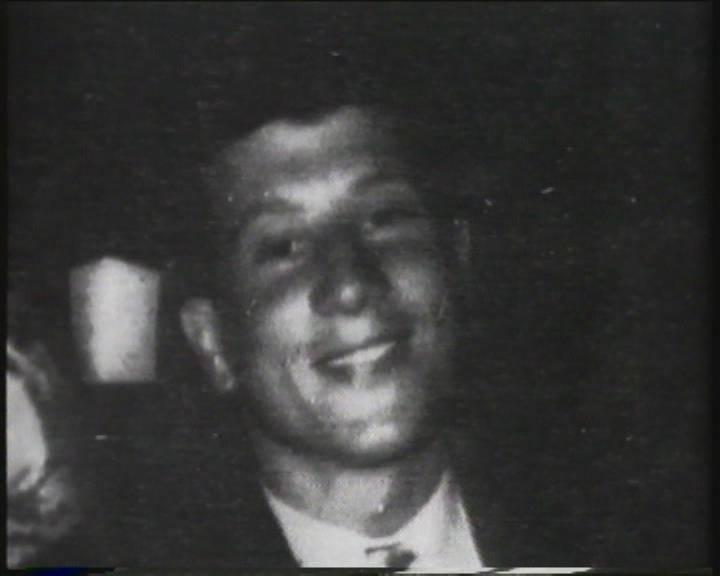

In October 1974 a headless torso was washed up on the banks of the Thames, the beginning of a series of grisly finds in the mud, body parts found to belong to North London criminal Billy Moseley. Eleven months later, the body of another London con, Mickey Cornwall, was found in a shallow grave in Hatfield. He’d been shot through the head. This is the basis of the latest in the ‘True Stories’ series, The Torso Murders, produced and directed by the eminent Rex Bloomstein, responsible for the award-winning BBC2 series, ‘Strangeways’.

Seven people were finally arrested for the two murders and tried in what was the longest murder trial in legal history. Four were found guilty, and two, Bob Maynard and Reg Dudley, still remain in prison protesting their innocence. Bloomstein’s film is a long, complex affair, but stay with it: not only is it splendidly redolent of colourful cockney crimeland types like ex-bank-robber Bobby King (‘You must be fuckin’ joking… Maynard couldn’t terrorise his own kids’) but it ends with a considerable bang.

The case of Bob Maynard is particularly distressing: having served the minimum recommended term of 15 years, he still languishes in Norwich jail unable to be released because of his continued protestations of innocence. The Home Office allowed Bloomstein to interview Maynard, but on the same day ‘refused him permission to spend a day at home. It seems as if they are giving with one hand and taking away with the other.’

The programme originated with Guardian journalist Duncan Campbell, who first wrote about the case in Time Out in 1977 and recently profiled Dudley in a newspaper piece which, says Bloomstein, triggered off his memory of featuring Reg in his earlier C4 series ‘Lifers’.

Looked at in the light of the Police and Criminal Evidence safeguards introduced recently, the convictions of Dudley and Maynard would have been thrown out before they reached the magistrate’s court, an opinion backed up by the fact that there was no physical evidence linking any of the defendants with the murders. Dudley and Maynard went down, says Campbell, ‘on verbal confessions that would have been inadmissable today and on doubtful testimony from known criminals’. Tragically and suspiciously, all the handwritten notes referring to the case were recently destroyed, but the programme provides startling new evidence from forensic linguistics expert AQ Morton of Glasgow University, whose opinion of the typewritten interviews is ‘rubbish as evidence’. Morton’s method has been applied in criminal cases both here and abroad, and suggests that their statements were altered.

Bloomstein admits that the programme loses from being unable to confront any of the police involved, ‘although Commander Bert Wickstead has made it clear that his views haven’t changed since his last interview in 1978.’ Bloomstein has ‘avoided reconstructions and dramatic soundtracks, the kind of thing which I think creeps in too much… they are appealing within the next fortnight and I just hope the programme influences things for the better.’ - TIME OUT, Steve Grant

“In 1975 Reg Dudley and Bob Maynard were given life sentences for killing two fellow villains after the longest murder trial in British history. They protested their innocence but Chief Supt Bert Wickstead, the policeman in charge of the case, had no doubts. Interviewed in the same year, however, Wickstead predicted that “some idiotic do-gooder” would reopen the case and convince a gullible public that the men were part of a wicked police frame-up. Rex Bloomstein’s film alleges just that. Even the judge conceded that oral confessions were the only evidence against the men. A defence barrister says no jury today would have convicted, indeed the case would have been thrown out by the magistrates’ court. The programme includes a new interview with Maynard, recorded this year at Norwich prison.” - THE TIMES, Choice

“Horror Stories

Thursday’s True Stories (C4) focused on the so-called “Torso Murders” of 1974, when four people were imprisoned for murder, two of whom are still inside. From extraordinary Home Office memoranda, it appears that these two - Bob Maynard and Reg Dudley - will not be released until they have “addressed their offending behaviour”, or, in other words, stopped protesting their innocence.

Though theirs was the longest murder trial in British legal history, they were convicted with no physical or forensic evidence, no eyewitnesses, no murder weapons, no signed confessions and little or no motive.

As a straightforward documentary of injustice, it would have been hard to better, but True Stories also presented a fascinating, and often rather comical, portrait of the East End underworld in the early 1970s. I particularly liked one of the crooks being called Ronnie Fright, and some of the more strait-laced interviews with ex-cons over pints of beer were unintentionally hilarious.

“‘E was always firing after Richards,” reminisced an elderly bank robber.

“Richards?” queried the interviewer.

“You’re not allowed to say it anymore,” explained the bank robber, smiling into his beer, “Richard the Thirds - birds.” - THE SUNDAY TIMES, Craig Brown