REXENTERTAINMENT

“The phrase that I have come to believe best sums up what the documentary film can most hope for, is to ‘undermine the simplicities’. The challenge is to present a much needed sense of flawed humanity not stereotypes.”

Rex Bloomstein

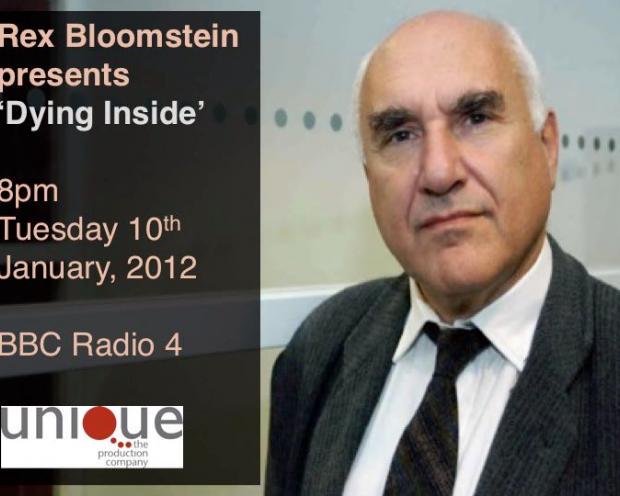

Rex Bloomstein has made over 150 single films, television documentaries and series and, in January 2012, presented his first radio documentary, Dying Inside for Radio 4. He is currently developing a number of further projects.

For full details about his work, follow the links below.

The building retracted into itself. She – soft flesh – edged her way out. It’s two years now. Two years since her mother buried herself past saving. There’s no gravestone yet. Just clean grass, waiting.

[from ‘The House’ by Aviva Dautch]

Award-winning poet, Aviva Dautch, lets us into the secret of her childhood home in Salford. From sleeping in the bath to emptying thirty-two tonnes of rubbish from the house after her mother’s death, Aviva shares what it means to be the child of a hoarder and how her lyrical, precise images seek to make order from the chaos in which she grew up.

This programme is a voyage into the past, but also one of discovery for Aviva, who has never before talked to others who have had similar experiences or to specialists in the field. She tells her story, weaving together her poems and conversations with

Background

Her mother barricaded her in behind household goods, newspapers, rotting vegetables, until the house became its own creature in the child’s mind….

Aviva’s mother suffered from obsessive hoarding syndrome, a condition now officially recognised by the World Health Authority as a mental illness, but when Aviva was growing up in the 1990s there was a culture of silence around the problem. Hoarding was the way Aviva’s mother created a place of safety, a refuge, but for Aviva their home became a prison.

Far from the stereotype of the sad, eccentric hoarder, Aviva’s mother was a successful paediatrician and geneticist, a member of the team working on the development of IVF She’d left the team not long before the first baby, Louise Brown, was born as she was pregnant herself (with Aviva). She would go on to become an expert in Tay-Sachs disorder. Academic studies have shown that hoarding is more common in women, especially women who are carers: social workers, nurses, therapists or, as in Aviva’s mother’s case, a doctor. There seems to be a strong link to trauma, with the onset linked to bereavement or loss – the hoarder’s post traumatic response is to literally bury themselves alive.

Aviva reflects on her experiences as the daughter of a hoarder, absorbing recent research that has explored how fear and shame lead children of hoarders to hide their living conditions from outsiders. Not only are they embarrassed about the condition of their home, their self-perception is that they are worthless as their parents seem to care about objects more than them. Secrecy about the home is intensified by fear of parental reactions. As children get older, the psychological cost of accommodating the disorder becomes more apparent. They become more conscious of their own vulnerability, helplessness, disgust and social isolation. Like Aviva, many become totally estranged from their families; some become hoarders themselves and others obsessively tidy.

The Program

Poet Aviva Dautch revisits her childhood as the daughter of a chronic hoarder.

Questions about how she or, indeed, others could cope with such conditions under the restrictions of lockdown inform how Aviva tells her story, weaving together her poems and conversations with friends: professional declutterer Miriam Osner, her former schoolteacher Sherry Ashworth, and actor Juliet Stevenson.

Juliet reads from the poems of Emily Dickinson, who spent much of her life in solitude but wrote expansively about the world. Aviva and Juliet explore why her poems reverberate for them in the current moment and discuss the positive aspects of isolation, the necessity of the arts for helping us feel less alone and how creativity can be a response to adversity.

The programme features poems from Aviva’s Primers Three sequence (Nine Arches Press: 2018) and her work-in-progress debut collection We Sigh For Houses, which has received an Authors’ Foundation Award from the Society of Authors.

Presenter: Aviva Dautch

Producer: Rex Bloomstein

Exec Producer: Brian King

Sound Engineer: Matt Peaty

Hebrew liturgical music sung by Michal Ish-Horowicz

About Aviva

Aviva Dautch teaches English Literature and Creative Writing at the British Library. She has a PhD in poetry and her poems, reviews and literary essays are widely published. She won the Poetry School /Nine Arches Press Primers Prize for Emerging Talent in 2017 and received an Authors’ Foundation Award from the Society of Authors in 2018. Her first full collection, We Sigh For Houses, is due to be published in early 2021.

‘Aviva Dautch is a powerful young poet, whose work engages very intelligently with serious issues, but who has a formal dexterity and a command of social tone that makes her feel approachable; she’s someone to watch for the future and someone to enjoy in the present.’ Andrew Motion

‘Aviva Dautch’s poetry is distinguished by its musicality, linguistic clarity and precision, depth of thought and feeling.’ Mimi Khalvati

Every year the Parole Board releases thousands of prisoners, including those convicted of the most serious violent offences. Rex Bloomstein made the first ever television series on parole in the 1970’s, and now 40 years later, has been given unprecedented access to go inside the parole system today and reveal how decisions are made.

He meets prisoners ahead of their crucial hearings and listens in on the entire process as parole panels interrogate the prisoner, prison and probation workers and psychologists. The panels finally conclude and explain their decisions - to release or not to release. The consequences of possibly getting it wrong, weigh heavily on them. For the prisoners, the tension leads to tears and anger.

Across the two programmes, Rex Bloomstein talks to Parole Board chief executive, Martin Jones and former chair, Nick Hardwick, who was forced to resign after the High Court quashed a parole panel’s decision to release serial sex offender, John Worboys.

Is the Parole Board sufficiently accountable, transparent and effective? Is its independence now under threat?

I wanted to consider the following elements to help reveal the parole process:

a) The prison – what parole means to them.

b) The prisoners – their hopes and expectations.

c) The parole board panel – the recording of several aural hearings with the agreed necessary safeguards.

d) Interviews with key figures on the Board to consider future developments for Parole and the implications for the prison system and society.

I wanted also seek to contrast the work of the present day Parole Board with excerpts from my seventies BBC TV series, Parole, which explained a number of aspects of the parole system and with it the opportunity of early release, the incentive to turn a life around, the chance for hope. Parole at that time was severely criticized as arbitrary and impenetrable. Some thought it actually cruel, as no reasons were ever given when a request for parole was turned down, often leaving a prisoner in a despairing limbo at the mercy of a ‘secretive bureacracy’.

The Parole Board had never been filmed and had refused all previous requests, but they finally agreed to this 2-part study broadcast in 1978. We followed 4 prisoners applying for parole and showed three different cases of a parole board panel’s discussion including an arsonist, a cannabis offender, and the case of a young sex offender followed by comments from the then chairman of the Parole board, Sir Louis Petch, which illustrate the assumptions and thinking at the time, and my critical conclusions on the parole system as it was practiced then.

It is interesting to note, that all the concerns, which were raised in the programs about the parole system have since been met. Parole has become automatic for prisoners serving fixed term sentences over 12 months. Prisoners have the right to an oral hearing - the right to be represented – the right to know reasons for refusal – the right to appeal. The Parole Board is no longer an advisory body but a type of court in its own right, dealing with mainly indeterminate sentences and reviewing disputed decisions to recall prisoners back to prison. Whilst questions continue to be asked over the Board’s independence and its transparency, its role had profoundly evolved since our filming.

Rex Bloomstein

GERALD is 49, and has spent more than half his life in prison. His weaknesses are heroin, and a penchant for armed robbery. The dossier on him runs to more than 300 pages, and includes robbing banks at gunpoint. The most recent incident occurred three years ago, when he broke the terms of his parole and attempted to rob a mobile-phone shop, threatening the owner with a syringe of blood.

He is now reapplying for parole, and, in his statement, declares that he is not a violent person. With the irony of a seasoned professional, the parole-board assessor regards this claim as “arguably surprising”.

Everyone was, throughout Parole: A calculated risk (Radio 4, Friday), scrupulously polite to one another; and I wondered whether our subjects were behaving themselves especially well for the benefit of the fly on the wall. Nevertheless, Rex Bloomstein’s documentary gave a valuable insight into the workings of a system which, in recent months, has attracted enormous criticism.

After the proposal to release John Worboys, the reversal of that decision by the High Court, and the subsequent resignation of the chair of the Parole Board, there was never a better time to examine what goes on in those parole-panel assessments.

Much has changed in the past 25 years. Prisoners can be represented by solicitors, and victims are given the opportunity to provide statements. Psychologists and prison staff are all consulted; and, in Gerald’s case, contribute to a picture of a genuinely reformed individual. He will be released, under strict conditions; and, as the man from the Parole Board was happy to tell us, the proven failure rate in such cases is very small. The trouble is that even one failure can be catastrophic for victims and for the reputation of the Board.

Rex Bloomstein meets musicians from around the world who are raising their voices against political, cultural or religious intolerance in the face of often brutal repression. He talks to artists whose songs have led to their imprisonment, torture and to the continuing threat of violence; artists who have been driven from their homelands, artists who, literally, risk dying for a song.

In one recent year alone 30 musicians were killed, 7 abducted, and 18 jailed by regimes, political and religious factions and other groups determined to curb the power of music to rally opposition to them. In Syria, singer Ibrahim Quashoush, was found dead in the Orontes River, his vocal chords symbolically ripped out.

Rex hears stories of tremendous courage and determination not to be intimidated and silenced. Egyptian singer Ramy Essam, tells of how he was brutally tortured after his songs rallied the crowds in Tahir Square during the Arab Spring. Two weeks later, after recovering from his injuries, he was back performing his songs of protest. Iranian singer Shahin Najafi continues performing around the world despite the issuing of a fatwa calling for his death, after his songs upset the religious leaders in his home country. He says: “At night I turn to the wall and slowly close my eyes and wait for someone to slit my throat”.

Amid tales of musical repression in Sudan, Tunisia, Burkina Fasso and Lebanon, come more surprising stories from Norway where Deeyah Kahn talks of death threats aimed at stopping her singing and Sara speaks about her struggle to sing the music of the indigenous Sami people.

The documentary filmmaker Rex Bloomstein gains unprecedented access to HMP Whatton in Nottinghamshire, the largest sex offender prison in Europe, to investigate how its inmates are rehabilitated for release. Since the revelations surrounding high profile figures such as Jimmy Saville, Rolf Harris, Max Clifford and the publicity created by Operation Yewtree, there are now more sex offenders in the prison system than ever before. Around 11000 out of a total population of nearly 86000 in England & Wales.

HMP Whatton, with its capacity of 841 prisoners, is a specialist treatment center for sex offenders – 70% of whom have committed offences against children, the rest against adults. Bloomstein has been allowed a unique opportunity to explore the methods used to confront inmates about their crimes and prepare them to go back into the community. The prison’s governor Lynn Saunders describes ‘Whatton as a great leveller, prisoners come from all walks of life’, and both child & adult offenders are mixed together in the prison’s many Sex Offender Treatment Programmes.

Candid interviews with prisoners are at the heart of this documentary as they reveal how treatment is helping them to rehabilitate but Bloomstein discovers a paradox. Many sex offenders feel intense shame and guilt about their crimes as indeed society would expect. However, he learns such emotions can be a huge barrier to the treatment process as Whatton’s staff work hard to restore their self-esteem deemed crucial to their rehabilitation.

As the majority of Whatton’s prisoners will be released Bloomstein ultimately considers the issue of risk – how certain can we be that these men won’t commit terrible crimes again? Programme facilitator Dave Potter says – whilst there is no guarantee he profoundly believes the work done at Whatton gives its sex offenders the vital tools to control their behaviour in the future.

Rex Bloomstein has been a pioneer of the modern prison television documentary from the award-winning series ‘Strangeways’ in 1980, to the ground breaking programme ‘Lifer - Living with Murder’ in 2003. His Radio 4 documentary ‘Dying Inside’, on older prisoners co-produced again with Simon Jacobs, won a Silver Sony Radio Academy award in 2013.

The Observer, Miranda Sawyer

This seriousness was also evident in Rex Bloomstein’s absorbing Inside the Sex Offenders’ Prison, on HMP Whatton, the largest sex offenders’ prison in Europe. Phew, this was a tricky one. Bloomstein met men who had committed the sort of crimes you hope nobody you love will ever have to deal with: from internet porn to rape and child abuse. Some offenders were very depressed about what they’d done, some were pragmatic, others remembered their anger, at the world and themselves. Bloomstein asked all the right questions, and acknowledged when the answers were awkward. There are 86,000 people in prison in the UK; 11,000 of those are sex offenders. HMP Whatton’s in-depth rehabilitation courses are a way of trying to deal with this enormous societal problem. A documentary that will stay with you for some time.

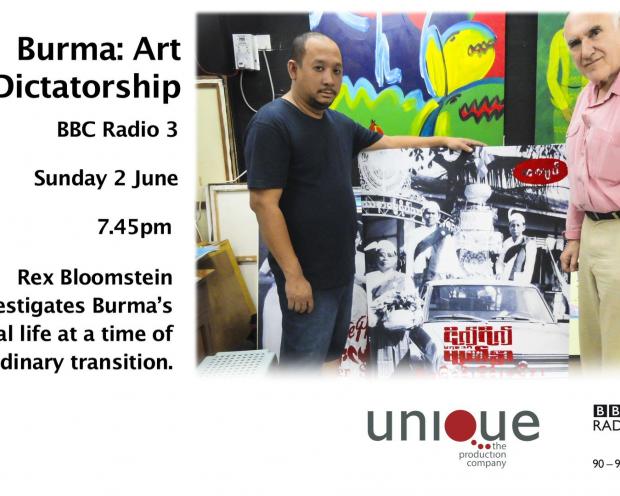

Burma is a country in transition. Supposedly freer now, then ever before. But is this really the case?

In 2010, I made This Prison Where I Live, a campaigning documentary film about Zarganar, Burma ‘s greatest living comedian, who had recently been released from a 35 year prison sentence. In Burma: Art Under Dictatorship, for BBC Radio 3, I returned to Burma to interview Zarganar, during the film festival that this unique and hugely popular artist has created. With Zaganar’s co-operation, it opened the way to talk to fellow comedians, writers, musicians, painters. How free were they to write, perform and play their music: how free were journalists to comment and enquire and others to engage in more radical art forms? What really was the state of freedom of expression in Burma?

Since the dramatic release of Aung San Su Ki, Burma’s artists were playing a key role in reflecting the country’s changing landscape. Art reflects society. What happens to its artists reveals what is really happening to the society and country its people live in.

However, after the so called ‘political reforms’ of those years, I encountered an artistic community who felt just about safe enough to speak out and who revealed how much censorship still existed. Painter and performance artist, Nyein Chan Su, described how ten government officials from the Censorship Board came to his gallery earlier in the year, only to forbid the color red on some of his politically themed paintings. Nyein Chan Su said, “red is too suggestive a colour for a regime responsible for so much bloodshed before the reforms”.

The film producer, Myo So, discussed his two year battle with the censors to get his 2010 film, ‘Nostalgia’, about the student uprising in 1988, distributed without significant cuts, even though the film contained no scenes of actual protest. Myo So was still fighting that battle.

One of Burma’s foremost contemporary poets, Zeyar Lynn, who spearheaded a new form of Burmese poetry, spoke of not having to use introspective and emotional language so characteristic of living under previous dictatorships.

Han Too Lin, Burma’s most radical punk singer, described the ways he’s tried to defeat the censors over his lyrics and his satirical radio show they had since banned.

What I discovered was the scale of the country’s cultural impoverishment, with so few places to study, view and exhibit art.

At its heart this program engaged with those artists who through their work were fighting an ongoing battle for history and memory – hoping they were freer to confront their past.

For this Archive on 4, Rex revisits these programmes and finds out what happened to those prisoners of conscience. Were some still in prison? What have those released done with their lives after torture and ill-treatment?

Of the 64 ‘Prisoners of Conscience’ shown on BBC 2 over those 5 years - over 40 were freed. Rex also reflects on the audience response, the politics of getting such programmes aired, the dangers of broadcasting them to the prisoners themselves and ultimately asks were they worth doing?

Prisoners featured in several of the series included :

So Sung - South Korea

The very first Prisoners of Conscience programme was presented by Sting in 1988. It featured So Sung, a student activist jailed by the South Korean Authorities and severely tortured. He was originally sentenced to death, but this was commuted to life imprisonment. In protest at his ill-treatment in prison he tried to commit suicide by setting himself on fire and is permanently disfigured as a result. So Sung was eventually released and is now a Professor in International Human Rights Law in Japan.

Mikhail Kukobaka - Russia

In and out of prisons, labour camps and ‘psychiatric hospitals’ for 18 years, Mikhail was serving a seven year sentence for anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda in the Perm 35 labour camp when he was featured in the 1988 series of Prisoners of Conscience. His offences included handing out a copy of the UN Declaration of Human Rights to co-workers. He refused to sign a confession but was released shortly after the broadcast and continued to be a regular NGO activist.

Riad al Turk - Syria

When he was featured in the 1989 series of Prisoners of Conscience, Riad had been in prison in Damascus for nine years for his opposition to the Syrian government. He had somehow survived the most prolonged and systematic torture which resulted in severe health problems, Riad al Turk was never charged or brought before a court. He was finally released in 2001 and lives in the Syrian city of Homs. Is he still alive?

Vera Chirwa - Malawi

One of Africa’s top women barristers, Vera had spent 10 years in prison in Malawi when featured in the 1991 series of Prisoners of Conscience. She and her husband had helped found the Malawi Congress Party, which campaigned for peaceful independence from the UK in the 1950s. They were kidnapped by Malawi police, tried and convicted of treason under the orders of President Banda and sentenced to death.

The trial was widely condemned as unfair and, after intense international pressure, Banda commuted their sentences to life imprisonment. Vera was released following the death of her husband in custody, and dedicated her life to human rights.

Manuel Manriquez - Mexico

Manuel was serving a 24 year sentence for the murder of a man he had never seen and whose name he did not know. Featured in the 1992 series of Prisoners of Conscience he is an Otomi Indian musician. Manuel was finally released from custody in 1999 after the Inter American Commission on Human Rights decided that his conviction was unfair and based on a confession extracted under torture. He lives in Mexico wher the admittance of evidence gained through torture remains a key human rights problem in Mexico.

Imen Derouiche - Tunisia

Imen was featured in the 1999 series of Human Rights Human Wrongs. She was one of 17 students arrested in Tunisia in 1998 after going on strike for improved study conditions. They were accused of being terrorists and she spent 18 months in prison before being tried on the basis of a confession extracted under torture. She endured beatings, injections and repeated threats of rape while in detention. Imen left Tunisia and is now a refugee in France.

In the late 1980s I noted a weekly column in the Times Newspaper called ‘Prisoners of Conscience’ written by the journalist and historian Caroline Moorehead. Of course the concept of ‘Prisoners of Conscience’ had been developed by Amnesty International, what Caroline was doing was to highlight individual cases of innocent men, women and children jailed in different parts of the world. It struck me that I could do the same in a series of short appeals for television. We first went to the UK’s Channel 4 who turned us down, and then approached the BBC who eventually accepted the idea.

We not only wanted to get the audience to watch such a series, but crucially to get them involved in trying to secure the release of these innocent people; to do what human rights organisations all over the world were doing – bringing attention to their wrongful imprisonment as well as the often appalling conditions and treatment such prisoners endured. The BBC eventually commissioned us to produce ten five minute programs to be shown Monday to Friday over two weeks and agreed that the series be transmitted to coincide with the 10th of December - Human Rights Day.

Presenters included two former prime ministers, distinguished scientists, famous sportsmen, provocative journalists, controversial writers, eminent actors and actresses, and yes, rock stars. The opening program in our first Prisoner of Conscience series in 1988 – was presented by Sting.

Some twenty five years later I wanted to revisit these programs, and find out what had happened to some of the people featured in the series – how had they fared? Were they even still alive?

So let me set out what were the main challenges in making the series; each program needed a minimum of visual evidence such as photographs of the prisoner, the prison he or she was held in and if it were not dangerous – photographs of the family as well. We had to give the facts and political context about each of the people featured in the countries that had imprisoned them and description of the tortures many of them had suffered as well as other violations of their human rights.

Our sources were primarily Amnesty International as well as Human Rights Watch and other human rights organisations and charities.

So what effect did we have? Audiences averaged a million and some 10,000 people overall either wrote or rang the BBC for an information pack that gave details of how and where to write on behalf of the prisoner. Of the 64 prisoners of conscience featured between 1988 and 1993 – we eventually discovered over 40 were free.

A 14 year old boy based in Eindhoven sent me this poem after watching the programs.

Jail in Japan

Eyes forward, no left, no right,

no daylight to be seen.

No people, no life to tell you why,

every night its all the same, change is not an option.

Pressure brings blood to your wrists that beg for freedom;

the windows with no glass aren’t on your side.

No one to see, no one to disagree with,

no one to tell it to.

No left, no right,

all is wrong that should make it right.

It was my hope that Prisoners Of Conscience and Human Rights Human Wrongs might have inspired other program makers in different countries to replicate the series, to do the same – using our example perhaps as a template. Because I believe with the right approach, you can make people care. But with the exception I think of Holland – it never happened. Perhaps it still should? At the very least the people featured in these programs were not forgotten.

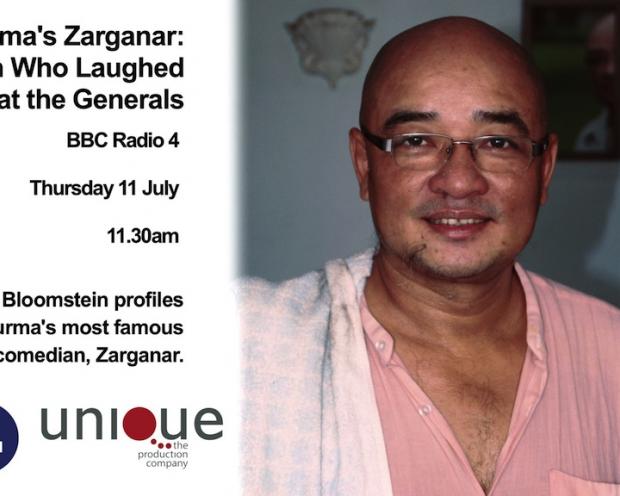

I filmed Zagarnar secretly in 2007 for a documentary on freedom of expression at a time when he was facing total censorship. We discussed how he became a comedian, how his fame led him to perform for the former dictator Ne Win. He told me how on his fourth jail sentence he survived five years of solitary confinement.

This footage remained unused. So when, two years later, I heard that he had been sentenced to 59 years in prison, on trumped up charges, I made a film that highlighted this injustice in the hope that I could galavanise people to put pressure on the regime to release him.

In this program for Radio 4, I return to Burma to interview Zagarnar again, contrasting his freedom now with the threat he talks about in my original recordings.

It was also to witness his first major show since his imprisonment, to hear him teaching comedy, to observe how far he will push the new regime to implement the promises of democracy and the price he and his family have paid.

Zaganar is Burma’s greatest living comedian but he is also much more than that. As a political activist, he was a fierce critic of Burma’s Generals who put him in jail several times, including 5 years in solitary confinement, for exposing their crimes and human rights violations.

I secretly interviewed Zarganar in Burma in 2007 for An Independent Mind, my feature documentary about freedom of expression. At the time Zarganar was totally banned from any artistic activity. In 2008, he was arrested again and sentenced to 59 years in prison, later reduced to 35 years for giving interviews to the foreign media about the desperate situation of hundreds of thousands of people made homeless by Cyclone Nargis.

In 2010, I secretly visited Burma again to make a new documentary about Zaganar’s imprisonment. Our film, ‘This Prison Where I Live’ was as much about a country living in abject fear as it was about Zaganar himself.

After a world wide campaign, Zaganar was finally released in 2011 during an amnesty of political prisoners following elections and a series of ‘reforms’ moving to a military backed civilian government. I then traveled openly to Burma to interview Zaganar in his home country for the first time since his release.

Arriving just after the recent sectarian violence between Buddhists and Muslims in Meitila, I heard how Zaganar was trying to mediate between the two sides. I learnt that the comedian had also been part of a commission looking at the violence and displacement of thousands of people in the western state of Rakhine.

Zaganar talked to me about continuing as an artist in Myanmar, about performing anyeint, a traditional form of theatre combining dance, music and comedy, even though he was working with a government containing people that imprisoned and tortured him.

Zaganar, which means “tweezers”, continues to use his unique satire to speak out as the country moves along a deeply uncertain path to democracy.

Presenter: Rex Bloomstein

Producers: Simon Jacobs & Rex Bloomstein

Dying Inside was my first documentary for radio and explored the growing phenomenon of older prisoners in our prisons, hearing at first hand from those who face the prospect of getting aging behind bars.

This country has the largest prison population in Europe with over 80,000 inmates costing the taxpayer on average £45,000 per year per prisoner. The fastest growing group within it are older prisoners, who number over 8000. This is largely due to sentences becoming longer.

At present there is no national strategy to deal with this issue. Prisons cope as best they can. Inmates are classed as older prisoners from the age of 50 when they are more likely to suffer with diabetes or coronary heart disease or have problems with their mobility.

For this first ever broadcast programme on the subject on British radio or television, Rex Bloomstein visited three prisons: HMP Maidstone, HMP Whatton and to the Elderly Lifer Unit at HMP Norwich, the first time that anyone from the media had been allowed in.

The programme revealed one of the more extraordinary aspects of this story, namely that over 40% of older prisoners are men convicted of sexual offences. An increasing number of them committed their crimes many years ago, but have been caught by advances in DNA techniques.

At the heart of this documentary is the testimony of the prisoners themselves, some of whom have been incarcerated for many years, while others have been sentenced late in life after their past caught up with them. Several have very serious health problems and face the possibility of ending their days behind bars – in fact dying inside.

Presenter: Rex Bloomstein

Producers: Rex Bloomstein & Simon Jacobs

A Unique Production for BBC Radio 4

“I never realised until I came into prison what the term ‘doing time’ meant. I’ve been marking time now for almost 30 years – ticking the days, months and then years off…I increasingly feel I am slowly dying away, ‘dead man walking’ as the saying goes.”

I read about David, an 82, year old man with terminal cancer. But unlike most men his ‘family’ are prison officers, care workers and fellow prisoners. David is serving a life sentence and will almost certainly die inside. I then discovered that the fastest growing age group in our jails are older prisoners.

In 2015 there were almost 12,000 men aged over 50 – four thousand of them more than 60 – one hundred more than 80 and five over 90. There are more than 300 women aged over 50 in prison in England and Wales. Almost 500 are over 70 years of age.

Today 16% of the prison population are aged 50 or over—13,636 people.

I became aware that these facts are creating huge challenges for prison, probation, health and social service staff within the system. Even more disturbingly, older people in prison are subject to discrimination and isolation, often eking out an existence on the wings and landings in our Victorian jails as well as our modern ones.

Dying Inside came to be the first documentary to investigate this subject for radio.

Many older prisoners are finding life in prison a kind of hell. Those unable to work, exist on a prison pension of £3.25 per week; they tell of being bullied and intimidated by the increasing number of younger drug addicted prisoners coming into jails. For those older prisoners who can be released, resettlement can seem terrifying in the face of the enormous challenges readjusting to the outside world. Some simply can’t hack it and remaining institutionalized is the only option:

The truth is that the aging process for older prisoner accelerates - 60 year olds have the bodies of 70 year olds. Many prisoners face the prospect of never leaving prison alive whilst many of these older offenders are literally dying inside.

So should we care? A number of these people have committed very serious crimes: murder, sexual offences. Many would say they deserve whatever they get, whatever they endure and should not be released. That view, lets call it the Daily Mail one, has certainly had its impact, especially through the New Labour years. There are now more people serving indeterminate life sentences in the UK than in all other 46 countries in the EU put together.

What is also clear is that there is no national strategy to deal with older offenders. Apart from HMP Norwich there is no hospital/hospice facility for the terminally ill within the prison system. Age Concern launched an Older People in Prison Forum in 2005, its local branches are piloting schemes while the National Offender Management Service is doing work in prisons such as HMP Whatton but admit not enough governors are doing the same.

There’s no policy framework because because no government wants to appear soft on crime and the criminal.

Longer and harsher sentencing, combined with an overall trend of an ageing population in the UK, has caused this warehousing of many more people than ever before. But is it sustainable? In purely economic terms, it’s costing a fortune in taxpayer revenue. Further concerns are the impact of overcrowding and scarce resources on the needs of older prisoners coupled with the Prison Service and the Parole Board being increasingly wary, even frightened, of taking the necessary risk to release people. The result has been many older prisoners staying beyond their tariffs.

The NHS now has the responsibility for healthcare in our prisons but only some of them have specialist services for older people. It appears that the needs of the frail and the sick prisoner are often largely unmet. For those terminally ill within the prison system – the lack of palliative care is a major concern because so many prison staff lack specialist training.

My aim was to build this programme principally around the testimony of older prisoners (principally in their 70s & 80s), illuminating the issues outlined above and exposing what will become a major concern in the years ahead. I wanted to ask what can we learn from their experience? What does the way we treat older offenders say about us and the prison system that contains them? What does it say about the nature of redemption, forgiveness, the need to punish and our respect for human rights?

Access

One of the main issues of course was access. Would we be allowed to conduct interviews and explore what it is like to be an older prisoner? The answer in principle was yes and agreement reached with the MOJ.

Further Facts

Older prisoners can be split into four main profiles, each with different needs:

Repeat prisoners. People in and out of prison for less serious offences and have returned to prison at an older age.

Grown old in prison. People sentenced for a long sentence prior to the age of 50 and have grown old in prison.

Short-term, first-time prisoners. People sentenced to prison for the first time for a short sentence.

Long-term, first-time prisoners. People sentenced to prison for the first time for a long sentence, possibly for historic sexual or violent offences.

Many experience chronic health problems prior to or during imprisonment as a result of poverty, poor diet, inadequate access to healthcare, alcoholism, smoking or other substance abuse. The psychological strains of prison life can further accelerate the ageing process.

The Prison Reform Trust, along with HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, the Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, Age UK and other organisations have called for a national strategy for work with older people in prison, something the Justice Committee agreed with and has stated: “It is inconsistent for the Ministry of Justice to recognise both the growth in the older prisoner population and the severity of their needs and not to articulate a strategy to properly account for this.”

The Care Act means that local authorities now have a duty to assess and give care and support to people who meet the threshold for care and are in prisons and probation hostels in their area.

With prison sentences getting longer, people are growing old behind bars. People aged 60 and over are the fastest growing age group in the prison estate. There are now more than triple the number there were 16 years ago.

Despite the significant rise in the number of over 50s in prison in recent years, the government projects only a modest rise in their numbers by 2022—14,100 people, an increase of 3%. The most significant change is anticipated in the over 70s, projected to rise by 19%.

45% of men in prison aged over 50 have been convicted of sex offences. The next highest offence category is violence against the person (23%) followed by drug offences (9%).137

234 people in prison were aged 80 or over as of 31 December 2016. 219 were in their 80s, 14 were in their 90s, and at the time of writing one was over 100 years old—87% were in prison for sexual offences.

Sony Award - Winner: Silver

Rex Bloomstein - Presenter/Producer

Simon Jacobs - Producer

Laura Parfitt - Executive Producer

Chris O’Shaughnessy - Sound Engineer

Philippa Geering - Broadcast Assistant

Unique The Production Company for BBC Radio 4

What the Judges said:

This was a remarkably strong documentary that confronted preconceptions, was thought-provoking and had moments of surprise. It was beautifully crafted and its eloquent silences sometimes spoke louder than words. The judges were impressed with how its calm, insightful interviewing style brought out fascinating, sometimes moving stories from people we rarely hear from, let alone think about.

The Observer, Miranda Sawyer

First, Dying Inside, about elderly prisoners. As our sentences get ever harsher and people are put away for longer, and as DNA techniques improve, meaning old crimes can be solved, our prison population is getting older. But Britain has no national strategy for older prisoners. Rex Bloomstein visited three prisons that contain inmates of 50 years or older. Such as Daniel, 65, who’d committed rape in 1982. More than 40% of older prisoners are people convicted of sex offences. “You do think about your crime,” said Daniel. “For 24 years I lived in a nightmare.” You wondered about his victim, whether their nightmare ever ended.

We heard, too, from Gerry, 69, who talked about his retirement. “I did my sport, I did my antiques, I did places I wanted to go that I couldn’t when I was at work. There was only one thing missing,” he said evenly, “and that was sex.” Your heart stilled, just for a second.

This documentary pulled you all over the place. It made me cry, and I’m still not sure who for. How to feel about Tommy, who was on his 24th year of a life sentence for murder? “It’s always there at the back of your mind. You’ll be eating and it puts you off your food. I knew the victim. He was a good friend of mine.” Tommy was in the UK’s only specialist unit for old (and very ill) prisoners, in Norwich. God’s waiting room, he called it. He’d seen 22 inmates die in the past four years. “I’m waiting on the wind to blow me one way or the other,” he said. Where will it blow you? asked Bloomstein. “To hell, I suppose,” said Tommy.

The Telegraph, Gillian Reynolds

The most thoughtful documentary of the week was Rex Bloomstein’s Dying Inside (Radio 4, Tuesday). Bloomstein usually makes TV documentary films. Radio suits him. This programme was about the large and growing segment of the prison population over 50, the age at which conditions of older life – diabetes, heart disease, arthritis – set in. The prisoners he spoke to were mostly serving long sentences for offences they either admitted (arson) or we were left to deduce (paedophilia). The interviews were clear, fair, courteous but left behind big streaks of doubt. One man confessed his offences, grievously penitent. Another, in a wheelchair, wanted to go home to babysit for his family. The listener was left to weigh what they said against the probability and the desirability of either, ever, being at liberty again.